The Business of Being an Artist

The Business of Being an Artist

A 2011 survey of art school graduates found that only about 40 percent were actually working as artists. If fewer than half of the graduates of medical school or law school were employed as doctors or lawyers, there’d probably be a congressional investigation. So why do we accept that art training doesn’t necessarily provide all of the tools for an artistic career? Well, because we know that making a good, consistent living as an artist is extraordinarily difficult. There’s no formula for success.

The artist’s life is full of uncertainty – creative and financial. And managing that uncertainty requires serious strategizing, adaptability, and persistence.

That said, it can be done. In fact, it’s being done all around us, as the hardy artists in this magazine illustrate.

Successful artists master two disciplines that might appear diametrically opposed – creativity and business. Of course, nobody can tell an artist what their creative direction should be; training and feedback from others will provide clues, but ultimately each artist must determine their own creative process and output. Your artistic DNA is unlike anyone else’s, like a fingerprint. So discovering your ideal art form – and knowing when and how to evolve – is a truly idiosyncratic endeavor. It requires knowing yourself intimately and listening closely to the muse within. It’s the ultimate act of faith.

Business, though, is different. If creative work requires looking inward, entrepreneurship mandates a continual scan of the horizon; it’s an external perspective. In successful artists, the intuitive right brain coexists with the empirical left brain – dream state, meet the bottom line. And though many artists start out intimidated by commerce, there is good news: While there aren’t instructions for creative achievement, there is lots of guidance for business success. Every step of the way, there is help. As our interview with show artist Rachel Shimpock confirms, artists don’t need to do everything themselves. You can ask for help, outsource, trade tasks, and make it all work.

For this career issue, we wanted to crack today’s code of business best practices. So we asked around and interviewed several artists described by their peers as business-savvy. Whatever your direction – whether you’re aiming toward commissions, galleries, a design practice, or something else – we hope you’ll see new possibilities in their advice. ~The Editors

Best Practices: Starting Out

Trust yourself, jump in, and remember to take breaks.

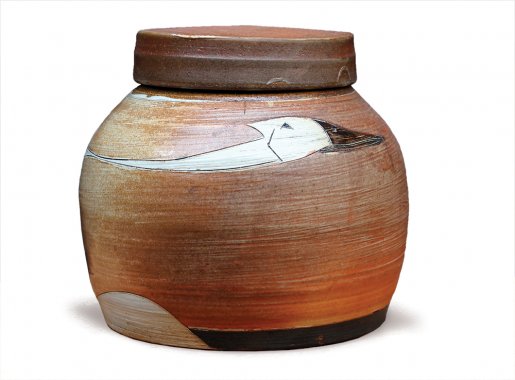

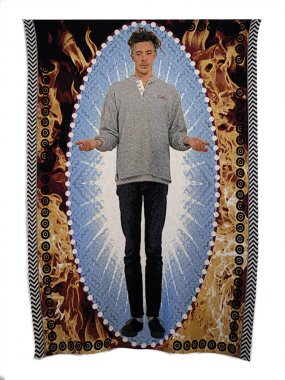

Matthew Krousey, ceramist, 33, Harris, Minnesota

On going for it: “On my own, I found that just trying things was a great way to learn how to be savvy. No one ever got anywhere by playing it safe. I never hesitated to try selling work at art fairs, galleries, farmers’ markets, tourist traps, etc. When you are starting out, you need to get the pots out into the world for people to see them.”

On balancing old and new media: Krousey uses Instagram and Facebook to publicize his shows and provide behind-the-scenes glimpses of his studio; he believes in the power of digital marketing. He also thinks, though, that more traditional forms of outreach are still relevant. “I firmly believe in maintaining a healthy snail-mail list,” he says. “No digital marketing tool performs better than a well designed postcard.”

On maintaining a network: Krousey’s potter friends double as his inspiration and his support. “I have kept up those relationships and hold them as my most valuable resource,” he says. “They are folks I can bounce ideas off, ask what shows they think are worth my time. And they are full of a lifetime of technical knowledge.”

Eleanor Anderson, textile artist and ceramist, 29, CORE fellow at Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina

On the perils of social media: Anderson is wary of posting too much in-progress work on social media platforms. “If I am in a period of experimentation, I try not to overshare starts of ideas on Instagram,” she says. “It feels like the fastest way to kill them. Maybe I can see their potential, but it’s not ready for an audience yet. They might need time to sit on my studio shelf before they get to the next iteration.”

On staying healthy: “I am definitely still figuring this out,” Anderson says. “My studio practice is much better when I get exercise. I like to run and bike, and I try to as often as possible. I feel like when I am literally moving forward, my thoughts also tend to move forward, instead of getting stuck.” Though projects can pile up, she thinks time away is beneficial in the long run: “Take breaks, even a week off, if possible. Going to museums and seeing art in other places besides the craft school environment always helps me to give myself more permission in the studio.”

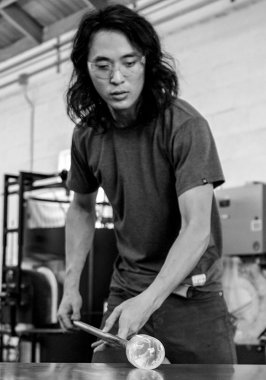

Kazuki Takizawa, glass artist, 31, Los Angeles

On balancing the creative process with the business side: Takizawa never worked in an office environment, so he learned business basics on his own. “Every step that I took brought me to where I am at today: learning how to write an invoice, making my company logo, designing and maintaining an artist website, hiring someone, company branding, accounting, etc. . . . I feel lucky that I enjoy doing office work as much as being creative.”

On pricing: “I have a worksheet I created that I use to calculate my time spent for the artwork, as well as my overhead. I take into consideration what similar work by other artists is priced at, just as a reference. I have an understanding that some lines of work are just more profitable than others. I have made things in the past which I did not make any profit from, but they have opened doors that led to where I am today.”

On maintaining wellness: Takizawa has struggled with depression, and mental illness is a central subject of his work. “Mental-health care is something that is on my mind on a daily basis,” he says. “Because I live at my workspace, I make constant efforts to take enough breaks. Being your own boss and running a business means there is a constant load of work to be done. Spending the time to not think about art and my business becomes a strong force behind my productivity. . . . By living small and simple, I am able to travel and invest my time and energy in something that I really want to create.”

Best Practices: Taking Commissions

Get eyeballs on your work and live simply.

Doug Meyer, Rustbelt Rebirth, furniture maker/sculptor, 43, Warren, Ohio

On getting through the lean times: “Psychologically, I’ve learned to laugh about them. If I’ve learned anything about my career, it’s that it will always have extreme ups and downs. The business of art is so unplottable as to seem mystical and purely faith-based. There are no maps, charts, or projections for climbing the invisible structure that we call an ‘art career.’ But something always pulls through in the darkest moment, so long as I fulfill the talent my hands were made for.

“Financially, as sales slowed, I adjusted. I took on jobs I wouldn’t normally do. I made legs and bases for other furniture makers and interior designers. I built a railing system for a commercial building. I even went to Massachusetts and put the metal cladding on a diner in single-digit temperatures in January.”

On social media: “I post lots of pictures on Facebook and Instagram. Being exhibitionistic is important. You have to throw yourself into the chaos if you want to find buyers – nobody is going to stumble into your studio and instantly support you.”

Gabriel Dishaw, sculptor, 37, Indianapolis

On navigating commissions: “I’m selective in what I do and the kind of compromises – time, cost, pricing, and approach – I make. Sometimes I’ve had to compromise on pricing for commercial commissions, but the sheer volume of people who will see my work is worth it, rather than [my work being] in someone’s house where only their circle of friends sees it.

“The best commissions are the ones that allow me to be me. The clients have a vision, and they are soliciting me to achieve that but allow me some creativity. I’ve gotten good at figuring out the ones where they’re too heavy-handed and how to prevent those offers from happening.

“But sometimes it pushes me in new directions. And I love it.”

On social media: “If you’re a visual artist and you’re not on Instagram, you’re doing something wrong. I post at 7 or 8 a.m. and 10 or 11 o’clock at night. The analytics say those are the big times. And I do meaningful blog posts. You’ll know whether it’s a good post or not by the number of likes and interactions. And that continues to change, so you modify accordingly.”

On navigating the business side: “I don’t need to be expert at everything; I need to know when I have an opportunity and when I need to consult an expert. I’m good at networking and finding people who can help. The person who commissioned one of my big projects was a creative director and he ended up putting together an entire branding kit for me.”

On pricing: “Look, people value things, and you have to put things out there. Some of it is trial and error.

“I never set out with a goal to sell my work. I was passionate about what I did, I loved the process. The outcome was this product that people want; no shame in that. I want my work to be out there, and I should be compensated for it.

“I’ve been experimenting with pricing for a higher-end market. But I also want more people to enjoy my work, so I’ve been thinking about, for example, doing smaller-scale work, so it’s more attainable.”

On surviving as a young artist: “It’s less about art and more about things that impact your ability to make choices in life. First, meditation: game-changer. You exercise physically to take care of your body; this is to take care of your brain. I recommend the Headspace app.”

On budgeting: “Live within your means, save, and educate yourself on financial stuff. Making poor decisions there handicaps you; it makes you have to make other decisions – about art, about your career. If you get those financial things straight, the sky’s the limit.”

Best Practices: Designers

Discipline, diversification, and a little disclosure are key.

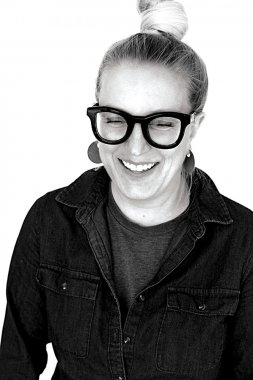

Molly Hatch, potter and designer, 39, Florence, Massachusetts

On legalese: To some, spending money on lawyers or agents may seem like a waste, but Hatch knows how useful their advice can be, especially for negotiating contracts and understanding licensing.

“There are some nuances in the licensing world where you need to know [whether you can] license the same artwork on bedding as you can on quilts. Are quilts a different category than bedding? Is quilting fabric a different category? Someone like an agent can tell you, ‘Yes, I know the answer to that question.’ ”

On learning to manage your finances: Take subcontractor gigs; they require you to pay self-employment taxes, which can teach makers in their 20s a lot about running a business.

“One of the biggest, scariest things is paying taxes and figuring out how to be self-employed. That should be something that you practice at that age and figure out how to do. It helps [you learn how to] track mileage and understand balancing the books and why you have a separate business account versus a personal account – all of those things.”

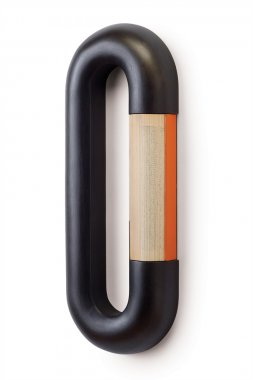

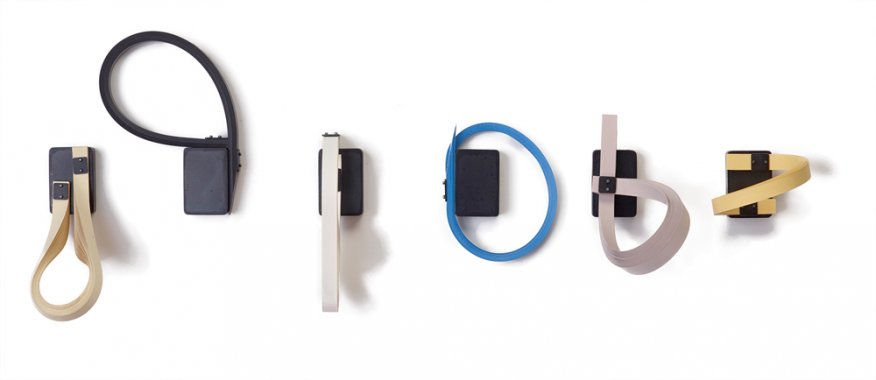

Abir Ali & Andre Sandifer, Ali Sandifer, furniture designer-makers, 39 and 45, Detroit, Michigan

On storytelling: Ali and Sandifer are private people, so they initially resisted sharing their lives on social media. But they’ve learned over the years that customers don’t want to just learn about a product, they also want to see the people behind the product. “We were told, ‘You need to own your story more. It’s OK. Stop being so humble and modest about the force behind the pieces,’ ” Ali says. So they tried it out. “We forced ourselves to be uncomfortable for a little bit and realized that there was a way to do it that felt OK to us. We draw boundaries and we’re not a complete open book,” she says. That works for them.

On several revenue streams: Don’t put all your eggs in one basket, Ali warns. The market for handcrafted, made-to-order furniture can ebb and flow, so she and Sandifer keep afloat by taking on a few large private commissions every year, as well as working side jobs. For the duo, this approach is about much more than financial stability, though – it also keeps them fresh. “When you diversify your business, you actually challenge yourself in different ways; you’re solving different types of problems. It’s a very healthy approach to design and innovation,” Ali says.

Uri Davillier, Neptune Glassworks, glass artist, 41, Los Angeles

On personal contact: Maintaining strong relationships with clients and vendors is critical, Davillier says. “I try to go to every design event I can make it to. After a grueling 12-hour day, the last thing I want to do is put my game face on, get dressed up, and find the mental energy to communicate with others. But looking someone in the eye and shaking their hand once every couple of months will do wonders for your business.”

On structuring your time: Are you your own boss? If so, Davillier suggests setting a work schedule. “It is incredibly difficult as a new business owner to give yourself permission to turn off,” he says. “The hustle is intense, and it is easy to think that answering an email at 10 p.m. is a good use of your time, but I have found that not to be true.” He says keeping a consistent schedule – in his case, starting at 7:30 every morning and shutting off around 6 p.m. – helps him stay healthy, physically and mentally.

Best Practices: Working with Galleries

Learn from others, and rely on friends for support.

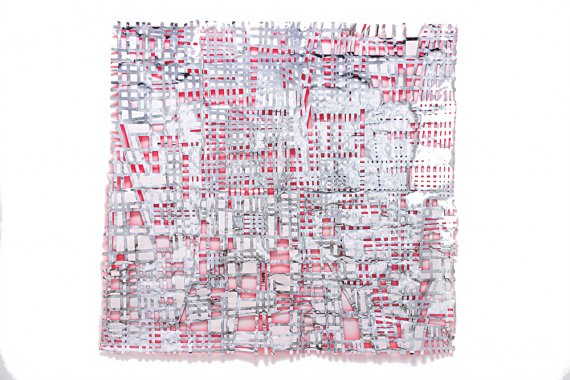

Leigh Suggs, paper artist, 36, Richmond, Virginia

On keeping up with gallery demand: Suggs considers herself lucky that her work is in demand, but even that good fortune is not without its difficulties. “The majority of my income comes directly from artwork sales, mainly through commercial galleries,” she says. “I have to constantly produce to keep this up, though. I have strong relationships with my galleries and keep them informed and well stocked with my work.”

On working for someone else: Suggs began her career at a design firm, which she says contributed greatly to her present success. “With that experience,” she says, “I was able to really see the inner workings of a studio. While it was very different from my work, the essentials are still the same. I learned quite a bit about managing cash flow, writing contracts, following up on in voices, good business practices, and, of course, customer service skills. Each of these things applies to my studio in some way, shape, or form – whether it’s building, protecting, or diversifying my practice.”

On the importance of community: “The most important thing to me, personally, is the supportive community I have built around me. On the days when I can’t show up or be consistent, I have a number of close artist friends who I can call on. These relationships have developed over the years and are deeply trustful ones. I can share my worries and concerns, brainstorm, cry, and celebrate with them. My community is the foundation that I exist on.”

Andrew Hayes, steel and paper artist, 36, Portland, Oregon

On paying dues: Starting out, Hayes worked as an assistant for sculptor Hoss Haley in Asheville, North Carolina. “During that time, I was able to see how a successful artist manages their time in the studio and at home,” he says. “For me, I need to find balance not only between my business and creative goals, but between my studio and home life. Working as an assistant allowed me to see that a productive life as an artist doesn’t mean a tortured existence.”

On taking care of business: Hayes believes in first things first. “I do my best to keep open lines of communication between galleries and clients,” he says. “I try to get to the studio early and make sure that my work and emails are taken care of. At times, I have a lot on my plate and rely on lists, calendar notifications, and apologizing, when needed.”

On doing it all: “Living on a speculative income, I have ebbs and flows of cash, which adds to stress,” Hayes says. “I do fabrication work to fill in the gaps, and that helps with money and keeping my hands moving in the studio. Physically, I often work long hours that can be very labor-intensive, but I do my best not to overexert myself.” Hayes lives with Crohn’s disease; he notes that the Affordable Care Act has been a tremendous help: “I went untreated for over a decade because I couldn’t get affordable care with a preexisting condition. . . . Since getting on ACA, I am living in remission and have no pain to speak of. I am terrified to think what will happen if I can no longer afford health insurance. I am deeply grateful for my wife, Kreh Mellick, who is also an artist and an extremely supportive partner.”

Best Practices: Craft Shows

Keep growing as an artist and ask for help when you need it.

Rachel Shimpock, The Original Kitchensmith, jewelry maker, 41, Long Beach, California

On greeting people at shows: “I’m an engager. I get my butt in the aisle and make eye contact. Sometimes a simple hello can make all the difference. I have my schtick.

“It can also scare people away – those are not my people. . . . I think it helps narrow the crowd.”

On booth design: “I wanted to go big. Like it or hate it, my booth got noticed. People who didn’t like my work still told me how they enjoyed the booth.”

On asking for help: Shimpock credits a designer friend as “the real brains behind the booth.” If you’re working in an area that isn’t your strong suit, find someone who has that talent and experience, and ask them.

On social media: Shimpock has a love-hate relationship with technology, but overall she says she loves its convenience and efficiency – “To be able to instantly expose your work to so many people, or just one, is amazing.” This is another area where she sought help, this time from her friend Rizzhel Javier, a photographer-graphic designer-artist. “She taught me the importance of the big-picture branding vision – all the website, print media, and branding needs to be consistent. The internet allows this,” she says.

On getting your foot in the door: Shimpock did the Hip Pop program at ACC shows for two years. “It was a lower-cost, lower-risk situation. I felt dumb, scared, and excited not knowing what to expect, but I was surrounded by others in a similar situation. Crisis averted!”

On working for “exposure” (unpaid): Shimpock thinks there are better ways to achieve the same goal, namely, wearing her jewelry in public “or having my friends and family also wear it (with cards on hand).”

Marylou Ozbolt-Storer, Fibrearts Inc., fiber artist/wearables, 69, Maple Valley, Washington

On drawing repeat customers: Reinvention is key, Ozbolt-Storer says – customers may already have a closet full of her work, so they may not need another mid-length coat. On the other hand, don’t sacrifice your artistic integrity. “Staying true to who you are and what you do as an artist is the brand that you create. Branding, although a fairly new buzzword, is not a new idea.”

On engaging with customers: “My customers are seeking an experience both in the booth and each time they wear one of my garments. Part of this process is educating my customer about the process and the value, as well as the vision of ‘what if’ and ‘how fun.’”

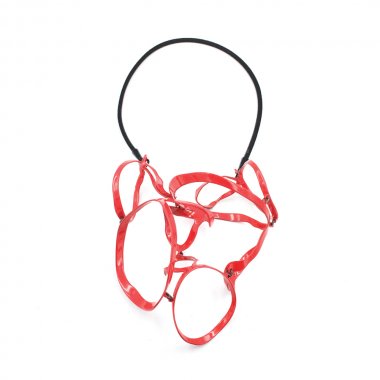

Laura Wood, jewelry maker, 35, Penland, North Carolina

On understanding her clientele: Wood believes in participation, whether with city art programs and professional organizations, or as a speaker on behalf of art jewelry. All these experiences, she says, help her learn how various audiences respond to her work and help build a larger community of enthusiasts. On the practical side, she keeps a contact list and makes a point of keeping contacts informed about her latest projects. “I believe that service to the field is key, and there is much to learn from simply being engaged,” she says.

On the business side: “Bookkeeping is a very important component to sustaining a career. The more records you keep, the more informed and knowledgeable your business decisions become,” Wood says. Even if you decide to farm out this job, “it absolutely has to be a part of how the art practice is run.”

Best Practices: Social Practice

Benchmark other artists and think twice before working for free.

Charity White, ceramist, activist, educator, 31, Chicago

On research: To find opportunities, White researches other artists who are at a similar point in their careers or even a little ahead. Looking at the grants they’ve received, the organizations they’ve partnered with, and where they’ve held residencies helps her narrow her focus. “It helps me figure out where I fall in alignment with others working in a similar way. It also helps me not waste time applying for things that are way out of my reach,” she says.

On planning ahead: When you get a grant, White points out, about a third of the money has to go toward taxes. “If you win a $2,000 grant, you don’t actually get that,” she says. So when you budget, be realistic about how much money you’ll actually have in hand.

On unpaid work: How do you know if an unpaid opportunity is worthwhile? “Look at who it puts you in connection with and what you would learn from it,” White says. “Am I volunteering at a soup kitchen and then getting connected with that organization and understanding homelessness through their eyes? How can that feed my artistic practice?”

Vic De La Rosa, artist and professor, 49, San Francisco

On learning to speak “grants”: To learn to write grant applications, De La Rosa recommends “workshops, workshops, workshops.” He’s taken part in a wide variety, from art-focused courses offered by local organizations to more general grant seminars led by the university where he teaches. “The mix of information has been valuable in getting a variety of feedback and helping me craft my voice.”

On fair compensation: “Students and young creative professionals should always be paid for their work,” De La Rosa says. “It is not only ethical but vital for developing their worth and the value of their endeavors,” he says. But friends who aren’t artists can honorably be put to work “for beer, snacks, and good stories,” he says.

On finding focus: “I assess the intention I have with my art regularly – not only regarding what I want to say with the work itself but also what audiences I want to reach and why,” De La Rosa explains. “When I define these criteria, any opportunities that do not support them are easy to bypass. Artistic opportunities are like bright, shiny objects, and we want to have or experience them all, but they can easily sidetrack you or become time-sucks. Defining and focusing on your mission allows the tough decisions to make themselves.”

Carole Frances Lung, aka Frau Fiber, artist and professor, 51, Los Angeles

On forming partnerships: Where’s a great place to hold community art events? Lung suggests checking out your local library. Not only are libraries great places to gather, but they also might support your work later on. “The first six months to a year, we hosted Sewing Rebellion events and schlepped [all the project materials] in. But once the libraries saw the sense of commitment community members felt for the project, some put it in their budgets to buy equipment and materials,” she says.

On practicing kindness: “I wish I had known when I was younger to be a little more patient and kinder to myself,” Lung says. “I felt like a failure at 26 because I wasn’t a rock star. And I know that happens for some people – they finish school and explode into something – but that wasn’t my path. It’s been such a journey, but I also think that’s what makes the work what it is now.”

Best Practices: Social Media Savvy

Want to connect with an audience online? Great. Here are a few suggestions to help you make a splash, whether it’s on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, or other channels.

1. Show us; don’t just tell.

Photos drive audience attention on every social media platform; posts without an image are often overlooked. Videos are also powerful tools. Take a short clip on your phone about an aspect of your work that’s hard to explain with a still image. The video does not have to be expertly edited to be highly effective.

2. Reel in readers with the right headline.

You have only a few seconds to get someone’s attention. Be bold, be funny, be memorable. Consider the specific audiences you encounter on different platforms. What gets a laugh on Facebook may not work as well on the professionally oriented LinkedIn platform.

3. Nobody reads anything anymore.

OK, that’s a slight exaggeration. But once you have your audience’s attention, make sure you keep their interest. Be brief and choose a communication style that reflects how you typically express yourself; a conversational tone is often a good choice, but go easy on the exclamation points, so you don’t sound like a 14-year-old. You can pack a punch in a single pithy paragraph. Add a hyperlink at the end of your post to where people can easily find out more.

4. Drive traffic to your website.

Link to your website in all your work-related postings. Make sure your website is updated and easy to navigate with no dead ends. Your artist statement and contact information should be easy to find. Include information with images of specific artwork, such as title, date, materials, and dimensions.

5. Make viewing quick and easy.

Readers will leave your post or website if the visuals take too long to load. Medium-size, low-resolution photos are sufficient for most online purposes.

6. Share at the right time.

Google “best times to share on social media” to find out the days and times that research shows are, on average, best for posting. Check for updates regularly, because what’s optimal today may have changed by next month.

7. The “social” part of social media.

If you ask questions or seek advice, people are often eager to help. Respond by “liking” their content, commenting on their posts, and sharing, if appropriate. This kind of engagement is a roundabout but effective way to market yourself. Follow the organizations in your field and support their efforts; they will likely support you in return.

8. Plan your posts ahead of time and be consistent.

Create a plan for posting and the overall result you’d like to see over time – more sales, more traffic, what? Post well-edited, interesting content regularly and engage your desired audience in unique ways. Bonus advice: Proofread thoroughly; don’t rely on spell-check.

9. Don’t be boring.

Many artists forget that social media wasn’t invented just for dropping marketing messages on your friends. Mix it up. Tell us about your work, but also let us know that you are a person with an interesting, if imperfect, life. Start discussions, join conversations, and contribute to the greater good.

10. Don’t overshare.

Striking a balance between work content and personal stories can be hard. Some people post too much personal content, while others may not share enough to keep things interesting. Where do you draw the line? Share only what you’d be comfortable saying out loud in a crowded room – what you post about yourself is how people view you. Does the world really need to know that your adorable kid just spit up on your shoulder or that you just burned your toast to a blackened crisp? Maybe not. Notable exception: If the image of the Virgin Mary appears on your toast, go ahead and tell everyone online. You just won the social media jackpot!

Other Resources

BOOKS

Master Your Craft: Strategies for Designing, Making, and Selling Artisan Work (2016)

By Tien Chiu

This book primarily has tips on creating, but a few chapters at the end cover pricing, selling, and entering work in shows.

Art, Inc.: The Essential Guide for Building Your Career as an Artist (2014)

By Lisa Congdon

Congdon covers the various ways artists can make a living (it’s not just selling work directly) and offers tips for potential career paths.

Grow Your Handmade Business: How to Envision, Develop, and Sustain a Successful Creative Business (2012)

and

The Handmade Marketplace, 2nd Edition: How to Sell Your Crafts Locally, Globally, and Online (2014)

By Kari Chapin

Chapin covers the nuts and bolts of business-building and marketing. The advice is tailored for makers; maintaining time and space for creativity is a must.

Crafter’s Market 2016: How to Sell Your Crafts and Make a Living (2015)

Edited by Kerry Bogert

This book contains reams of practical advice – everything from tips for a positive collaboration to listings of shows and magazines to approach. It also includes a subscription to artistsmarketonline.com, a handy catalogue of opportunities for makers.

The Crafter’s Guide to Taking Great Photos: The Best Techniques for Showcasing Your Handmade Creations (2012)

By Heidi Adnum

Adnum shows you how to present your work in the best possible light, essential for the internet age, when a good photo can make browsers linger on your website (and a poor one can make them flee).

PERIODICALS

Sunshine Artist

Aimed at show artists, this monthly magazine focuses on fairs, festivals, and the like. The comprehensive listings include events both big and small.

Handmade Business

This monthly publication is an inexpensive resource for makers interested in a variety of tips; a free monthly newsletter offers another way to keep up to date on show listings and more. When you sign up for the newsletter, you can also download Bruce Baker’s e-book Ultimate Guide to Handcrafted Success. Overall, Handmade’s content is short and sweet, offering a quick introduction to topics that you can research in depth elsewhere.

FREE ONLINE TOOLS

The Creative Entrepreneur Podcast

Hosted by Bob Baker

This free podcast, ideal for listening to in the studio, provides inspirational interviews with successful creatives and offers advice on topics such as marketing and how to reach your creative goals.

Field Guide for Ceramic Artisans

Recent grads interested in a career in ceramics can check out this website packed with information and resources to get you on your way. Chapters discuss everything from understanding your student loans to finding employment and shipping your work.

The Professional Guidelines

Edited by Harriete Estel Berman

Harriete Estel Berman’s comprehensive webpage helps artists improve and standardize their business practices. Look for model consignment contracts, a checklist for preparing for an exhibition, and tips for getting into a juried show.

COURSES, COACHING, AND TOOLKITS

Artists Who Thrive

Ann Rea dismisses the myth of the starving artist: Her course teaches artists how to turn a passion into a sustainable, steady business. In order to graduate from the course, students must make back their tuition fee in art sales.

Craft Lab Webinars

Society of North American Goldsmiths

Jewelry artists can learn how to recognize and adapt to changing markets as well as pursue innovative business solutions through these online professional courses offered by SNAG.

Designing an MBA

Metalsmith Megan Auman provides one-on-one coaching sessions as well as video tutorials about topics such as marketing, pricing, branding, and growing your business.

Work of Art

Springboard for the Arts’ Work of Art toolkit teaches artists of all stripes fundamental business skills, from portfolio design to funding.

INTERESTED IN THE SHOW CIRCUIT?

ACC’s Hip Pop program can be a good way to test the waters. The juried program introduces emerging makers to the process at a reduced cost.

GRANT WRITING

Check out the art organizations in your region – many offer grant writing courses and other resources. There are too many to list here, but Google can help you find what you need. The American Craft Council’s Resources webpage also offers a comprehensive list of craft museums, organizations, and schools.

PRO TIP

Whether you’re writing a grant application, an a advertisement, or an email, grammar and spelling count. Apps such as Grammarly or Hemingway Editor can help you make the right first impression.