Button Man

Button Man

In the hands of Beau McCall, humble buttons become poetry.

Consider Redpotionno.1, a sculpture he created for the 2014 group show “I Found God in Myself,” which celebrated the 40th anniversary of Ntozake Shange’s acclaimed play for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf. Inspired by “One,” a poetic monologue by a character known as the Lady in Red, it’s a cast-iron clawfoot tub covered in buttons, most of them red. Inside, the subtle figure of a woman reclines, cleansing her body and spirit, leaving a residue of stars and flowers, glitter and rhinestones, all rendered in whimsical buttons.

To conceive the work, McCall drew on a memory of the 1982 PBS production of the play, with actress Lynn Whitfield as the Lady in Red. “She was young, sensuous, just oozing sex appeal across my TV screen. I never forgot,” he says. At the exhibition opening, he got to meet the playwright herself. Looking at his interpretation of her poem, she said, “No, that’s not Lynn Whitfield, sweetheart. That’s me. This is about me,” he recounts with a chuckle.

Such are the special moments McCall enjoys these days as an artist in full bloom, one who has worked exclusively, devotedly, with buttons for the better part of four decades. A longtime New Yorker based in Harlem, he uses buttons – hundreds and thousands of them – to tell stories: big, overarching narratives of life, love, family, and the African American experience, but also the tiny tales contained in individual buttons.

He loves everything about buttons: their history as ornament and fastener, the endless variety of designs, even the different sounds they make when hit together. (Shell and pearl are “high-pitched, clicky”; plastics have a flat tone, “like tap dancing.”) He makes jewelry and small objects but also wall hangings and freestanding pieces. “I like a large canvas,” he says. “The more buttons, the more of a story I can tell.”

His own story began in Philadelphia, where he was born in 1957. His earliest ambition was to be a roller derby star – “I would put my skates on and just glide.” But at around 10, he became enamored with his mother’s strappy sandals. “I asked would she buy me a pair? She said she couldn’t, because they were women’s sandals.” Undaunted, McCall cut up his Keds and attached colored wire left behind by the man who’d installed their telephone.

“I said, ‘Mom, these are boy’s sandals. I made them.’ She was flabbergasted.” From then on, she nurtured his creativity, enrolling him in art programs and making sure he always had whatever supplies he needed as he went through material phases: macramé, papier-mâché, toothpicks, terrariums, even leftover chicken bones he’d turn into jewelry.

He got into fashion in his teens and taught himself to sew by taking clothing apart and putting it back together to his own liking. He bleached his jeans, wore them with one leg cut off – “Flo Jo gets the credit for that, but I did it way before she did” – and added embellishments. His flair was such that nobody gave him flak for his personal style, which was gender-neutral ahead of its time. “I just felt like clothing didn’t have a sex. If I could pull it off, then I would wear it.” Down in his parents’ basement, where the ironing board was set up, a jar of odd buttons sat on a stairstep. “Every time I ironed my clothes, I would stare at it,” McCall remembers. “After a while, I started having this dialogue with the buttons. I opened the jar up, took some buttons out, looked at them, put them back. This went on for a couple of months. Then one day it hit me: I should utilize these.” Soon he was decorating his sweaters and jackets with buttons, and turning heads wherever he wore them.

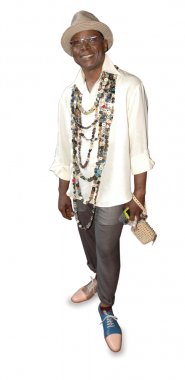

After high school, he headed to New York, hoping to break into the fashion industry. Through the 1980s and into the ’90s, he was active with the Black Fashion Museum in Harlem, which put on shows where designers could cultivate their craft and be seen. He got further exposure going to art openings around the city clad in his button-bedecked creations. He had some success selling his work and was even written up in Women’s Wear Daily.

By the late ’90s, however, he was beset by personal problems, including the loss of many friends to AIDS. “I stopped creating for maybe 10 years. I could not muster up the energy. It was not a good period for me.” Then he met his partner, journalist and curator Peter “Souleo” Wright, and “my life changed. He understood me as an artist.” With Souleo’s encouragement, McCall resumed working with buttons in 2010, this time in a sculptural way.

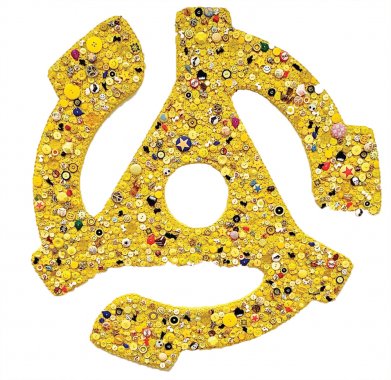

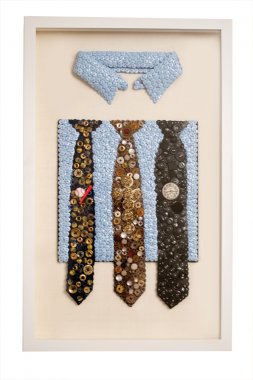

His work has since been in a number of traveling exhibitions, several of them organized by Souleo, including “I Found God in Myself.” Souleo also conceived “Motown to Def Jam,” a 2013 group show about the great blues, soul, and hip-hop record labels and the eras reflected in their music. For that one, McCall made three works: a 3-foot yellow 45 rpm disc adapter (a nostalgia item for boomers; “young people have no idea what it is”); a crown in tribute to Stevie Wonder’s song “Happy Birthday,” celebrating Martin Luther King Jr.; and Dear Mom, inspired by the 1973 hit “I’ll Always Love My Mama” by the Philly group the Intruders, showing McCall’s arm proffering flowers to his mother, still his biggest supporter.

“Music is a big part of my life,” says the artist, who works late at night, with jazz, funk, and “a little country-and-western here and there” in the background. “If it’s good to my ears, I’ll listen to it.” His buttons can come from flea markets, thrift shops, and his mother’s collection. “When I get them secondhand, they’ve had another life. I give them a permanent life, their last destination,” he says. For big orders and specialty items, his main sources are Lou Lou Buttons and Tender Buttons, both in New York, where he’s a kid in a candy store. He buys white buttons in bulk and has them dyed to order. To make a piece, he often has plexiglass laser-cut into the desired shape, covers the form in fabric (usually sturdy denim), then sews button after button, in two layers – a bottom, uniform base and a decorative top. It takes anywhere from three to six months of patient handwork before he can present the finished product to the world.

“Sometimes I stand back and watch the response of the folks viewing my work, and I get a charge,” he says. “It makes people happy, smile, feel good. It’s well worth it, after all the time and effort and love I put into these pieces.” And does he still wear his creations to show openings? “Of course,” he says, laughing merrily. “Jackets, jewelry, armor, bracelets. So when you see me, you know which work belongs to me.”

For McCall, his art is a way to leave his mark. He refers again to a Ntozake Shange poem, a line about wishing to be unforgettable, a memory. “This is how I feel about my work. I want to share my legacy,” he says. “I feel like I’m just getting started, still emerging. This adventure is just blowing my mind. It’s a very good time.”