The Caribbean

The Caribbean

On the islands of the West Indies, functional tradition and artistic innovation mingle.

In much of the West Indies, the arts and crafts scene blends British and African traditions, and nowhere has this blending of cultures come alive more than at Caribelle Batik, on the island of St. Kitts. The island is small – only 68 square miles and fewer than 35,000 residents – and is blissfully absent the generic tourist façade seen in many Caribbean vacation spots. It’s a place created and enjoyed by the locals.

The Caribelle workshop and retail outlet was started by Englishman Maurice Widdowson more than 30 years ago, turning the wax-resist fabric-dyeing technique that he had learned from the Tonga in Zambia into a distinctly Kittitian art form.

When Widdowson first arrived in St. Kitts, there wasn’t much of an art culture. “In fact, the schools didn’t even have art as part of the curriculum,” he says. He purchased historic Romney Manor, an estate once owned by one of Thomas Jefferson’s forebears, and began training locals – many of whom made their living chiseling gravel from rock – in the craft.

Whether in Africa, the Far East, or the Caribbean islands, batik is traditionally crafted using natural dyes made from local berries and minerals, and that holds true at Caribelle. “Our approach to batik is using the traditional format of molten wax,” Widdowson says, “but without any inhibiting factors of tradition”; their palettes and designs are pure Caribbean.

Yvette Coker, one of the original em-ployees, fell in love with batik during training. “My favorite thing is the pride I feel when I see the finished product,” she says.

“I like the fact that it’s labor-intensive,” Widdowson says. “It employs a lot more people on the island” that way. Caribelle Batik is more than a business, he says. “It’s fulfilling a dream, really.”

On nearby St. Lucia, another British transplant has been artistically inspired by her surroundings. Finola Prescott came to the island at age 6; by college, she was writing papers on the history and prospects of crafts on St. Lucia. As an adult, she has worked to develop craft markets and skills, as well as her own art.

The emphasis of traditional crafts in St. Lucia has been squarely on function, she says. During the colonial period, when the island changed hands between the British and French 14 times, local culture and tradition were fragmented. “This has left St. Lucia with a very sparse legacy of what I call a visual language.”

Prescott began creating jewelry and paper objects including bowls, lampshades, and other home décor items. “I love learning and experimenting, so I tend to seek out and absorb all kinds of skills and influences.” She thinks this inventiveness is encouraged by island life; because of the small population and limited availability of materials, artists tend to be creative with what they’ve got.

“St. Lucians are highly expressive people, and master crafters are perhaps limited only by their lack of exposure, and access to tools,” she says. That said, St. Lucia has the largest number of traditional potters in the English-speaking Caribbean. But Prescott fears the tradition will die out. Not a single child of the 30 or so working potters (almost all women) is interested in continuing the craft, she says.

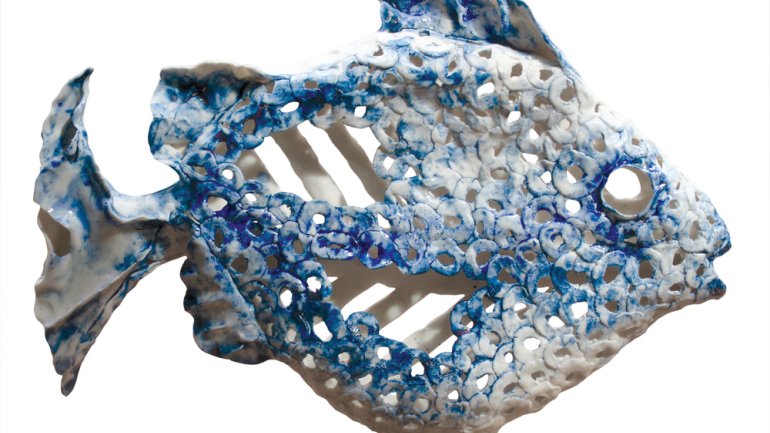

On Antigua, native-born ceramist Michael Hunt returned to the Caribbean with his English wife, ceramist Imogen Margrie, to launch Cedars Pottery in 1996.

The couple make their work collaboratively, producing a range of hand-thrown tableware, carvings, sculptures, and wall pieces, and an eclectic mix of architectural, one-of-a-kind commissioned pieces.

“The tactile nature of clay excites me,” Margrie says. “My pieces tend to be about form and texture, with a limited amount of color.” Hunt says his creativity is fueled by the natural and urban geography, from rock forms to architecture. Even obscure notions from religious texts can inspire him.

Many of the region’s craft works find their way to Design Caribbean, a fair in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, that takes place every fall. The Caribbean Arts and Crafts Festival, held in March in the British Virgin Islands, is also a big draw. Visitors can expect to find everything from woven baskets and handmade furniture to hand-fired pottery and sculpted metals by artisans representing about 20 Caribbean islands. The event also promotes the use of locally sourced and recycled materials, in keeping with the region’s history of transforming natural island materials into culturally significant creations.

Hilroy Fingal of the island of Dominica embraces this practice, transforming throwaway objects such as bottles, rocks, and calabash gourds into beautiful and functional pieces, many freighted with symbolism in their surface decoration. He also creates jewelry, lampshades, vases, paintings, and drawings, all showcased at Balisier, a restaurant in the Garraway Hotel.

A six-part island-by-island television documentary, The Power of Craft, is in production. While many traditional crafts, such as pottery and basketry, continue largely unchanged, more contemporary influences find their way onto the island scene – a juxtaposition the documentary seeks to capture.

Shelley Seale is a freelance journalist and author based in Austin, Texas. Her stories have appeared in National Geographic and USA Today, among other publications.