Celebrating the Spirits

Celebrating the Spirits

Artists tap life-affirming, death-embracing motifs from their Mexican heritage.

El Día de los Muertos – the Day of the Dead – has long been an important holiday in Mexico, a vivid blend of indigenous and Western beliefs, celebration and mourning, the pleasures of life embraced against a backdrop of the inevitability of death. Now, thanks to grassroots celebrations and museum exhibitions, it is becoming a seasonal event in the United States as well.

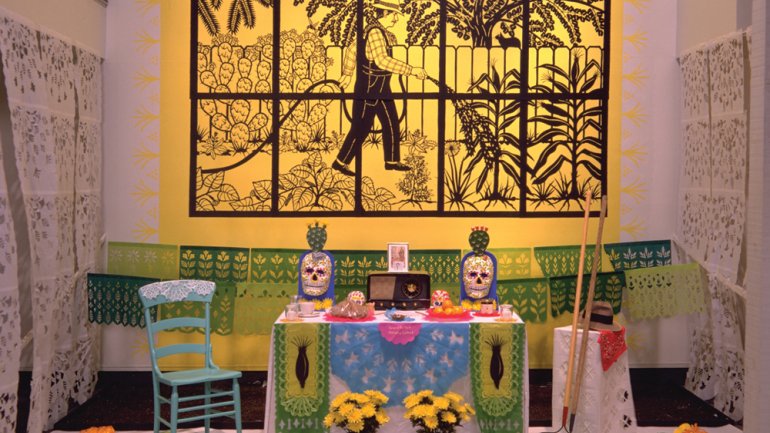

Whereas death is often considered a taboo, or at best, an uncomfortable subject in the United States, in Mexico, it is accepted as a fact of life, and a common belief holds that relatives’ spirits come back on the Day of the Dead for a joyful visit. Skulls, marigolds, and colorful banners of papel picado, tissue-paper cutouts that decorate every kind of celebration in Mexico, are familiar motifs in the festivities. For Mexican American artists, the Day of the Dead offers an opportunity to celebrate their ties to the diverse and ancient culture of Mexico, as well as to their own families and memories.

The holiday can spread out over days. Milwaukee artist Jose Alfredo Chavez, who grew up in Michoacán, recalls welcoming the spirits of deceased children on November 1, then clearing away the toys and candy, and bringing out beer and spicy dishes for the spirits of adult relatives on November 2. Chavez’s family spent days tailoring each ofrenda (literally, “offering” – elaborate altars or shrines that in-clude flowers, fruit, and photographs) to a particular departed relative. “We take it very seriously,” he says.

Chavez makes Day of the Dead skeleton figures out of papier-mâché – often representing figures from folk and popular culture, such as devils, wrestlers, and celebrities.

Wence Martinez, from Teotitlán del Valle, a village near Oaxaca celebrated for its weavers, now lives and works with his wife, Sandra, also an artist, in Door County, Wisconsin. Martinez remembers seeing his father and grandfather carefully watching hawks and vultures gliding in the sky, because these birds were considered to be messengers, their actions filled with meaning.

“Birds are spirits that come to watch over us,” he says. “When we die, children become butterflies, but adults become birds.”

Martinez, a onetime shepherd, sources his wool from back home in Mexico, and as much as possible relies on natural differences in the fleeces for color variations. He uses an abstracted hawk as a recurring figure; one work, Floating Hawks, was included in an ofrenda in the 2003 Day of the Dead exhibition at the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago; the show is an annual event, which the museum bills as the largest of its kind in the United States.

Carmen Lomas Garza, a San Francisco-based artist, has created numerous ofrendas for important people and places in her life over the years: They include one for Frida Kahlo, with a paper sculpture of Doña Sebastiana with her oxcart, a traditional figure of death in Mexico and the American Southwest; an enormous ofrenda for the great Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán; and one for her grandfather, Antonio Lomas, that commemorates his skill as a gardener.

All contain elaborate constructions based in one way or another on papel picado. (Garza can break down Doña Sebastiana and her oxcart, lay them flat, and stash them in her trunk. “I try not to make too many things that don’t fit in my car,” she says.)

Garza made her first cutouts as a child, helping her grandmother create embroidery patterns in her hometown of Kingsville, Texas. Today she transforms paper designs digitally into airy metal installations like Baile, which was cut into copper and then blown out with pressurized water. Baile, permanently installed in the San Francisco International Airport, depicts costumed dancers, seen through the window of an artist’s studio.

Houston serigrapher Carlos Hernandez draws on many motifs in his gig posters that he saw folk artists use when he was a boy visiting relatives in Mexico. Later, on trips to Santa Fe, New Mexico, he delved into images specifically associated with the Day of the Dead. A Lubbock, Texas, native, Hernandez says, “I grew up with The Brady Bunch and pop art, but I loved all that stuff.”

He relates to the Day of the Dead most strongly in terms of remembrance, and often uses the motifs for departed musical figures, “to pay homage to those fallen heroes.” A major influence is José Guadalupe Posada, a seminal Mexican printmaker of the 19th century, whose skeletal figures are Day of the Dead staples.

The de la Torre brothers, Einar and Jamex, were born three years apart in Guadalajara, but in the 1970s moved to a beach town in Southern California in time for high school. Now based in San Diego and Baja California, they have gleefully absorbed all kinds of Mexican imagery – as well as other icons from all over the world – in their exuberant glass and mixed-media pieces, including skulls and skeletons.

The de la Torres do not generally participate in Day of the Dead exhibitions; they are leery of seeing the day turn into “the Mexican Halloween,” Einar says. He understands why museums do the exhibitions, though; they tend to be very popular, even with Americans who have no ties to Mexico.

“But we don’t think we have much to add to that discussion,” he says. “We think we’re doing our job if we say, ‘Hey, death is guaranteed. What’s wrong with thinking about it?’ ”

Two museums with long traditions of Day of the Dead celebrations have exhibitions this year: The National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago, through Dec. 14, and the Oakland Museum of California, Oct. 8 – Jan. 4. The Smithsonian Institution has a virtual exhibition. Delia O’Hara is a Chicago-based freelance writer.