The Compound that Sam Built

The Compound that Sam Built

The great American woodworker Sam Maloof was a “people person” to his core, keenly interested in and engaged with the world around him. This was clear when I had the privilege of spending time with him several years ago at the Sam and Alfreda Maloof Foundation for Arts and Crafts in Alta Loma, California, just east of Los Angeles.

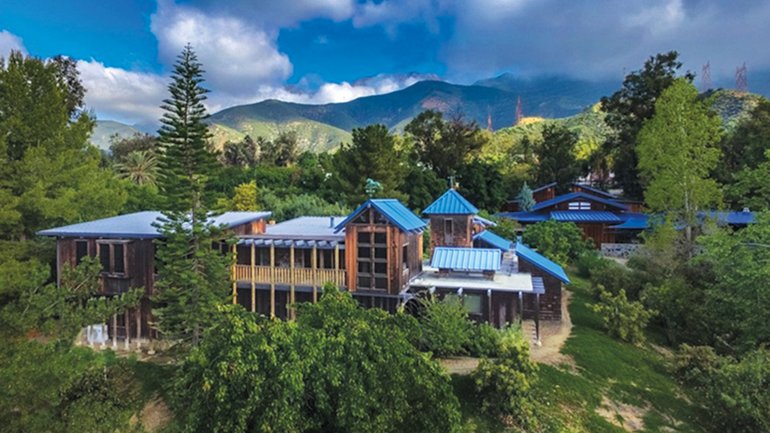

At the heart of this 5½-acre compound is the extraordinary redwood house Maloof designed and built for himself, his first wife, Alfreda, and their two children, starting in 1953 and adding on over subsequent decades. When I met him there, he was just shy of his 93rd birthday, friendly and humble, and in admirable shape. “I weigh now what I did in high school in ’34, so that’s not bad,” he quipped. Although his knee was giving him trouble, he took obvious pleasure in walking visitors through the sprawling residence, even up the celebrated spiral staircase he’d carved by hand.

“The whole house is sort of a gallery,” he noted, in an understatement. Warm, homey, and replete with handcrafted details, the rooms were filled with not only his own creations, but also those of friends and colleagues – pots by Harrison McIntosh, enamel work by June Schwarcz, turned wood by Bob Stocksdale, and fiber work by Kay Sekimachi, among others – along with work by emerging makers. “I’ve never, ever bought because it was a certain artist,” he said of his collecting. “I buy what I like. It could be an unknown, it could be a very-well-known.”

Just as the rooms embodied a sense of community and connection, Maloof mentioned more than once the personal bond he enjoyed with his clients. “The nicest thing is I make friends with everybody I work for,” he said. “I think it’s very important. It wouldn’t be much fun if I just made furniture and didn’t know where it was going.”

His customers included Presidents Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter; the latter, an amateur woodworker himself, became an especially close friend.

It was mind-boggling to consider that the fabled house hadn’t always occupied the same spot. Back in 2000, to make way for a freeway extension, it had been designated a historic property, dismantled, and moved 3 miles from its original site to its current one, a former lemon grove in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains. “It was hard. Freda had just gone away,” Maloof recalled of the move, using the poignant phrase he always did to refer to his wife’s death in 1998.

With the relocation, “the house that Sam built” became a museum and the centerpiece of a vibrant cultural center. A new dwelling was constructed on the grounds for Maloof and his second wife, Beverly, who added an artful garden of drought-tolerant plants native to California and the Mediterranean. He stayed as productive as ever in his woodshop, assisted by “the boys,” as he called his small, longtime team of craftsmen. “I’m doing work now for the third generations of the same families. There’s a good feeling about it. I have hundreds of things in my head that I want to do,” he told me on that day in January. He worked, it’s said, right up to his death the following May.

Today the foundation pursues an expansive mission, grounded in continuity while embracing the new. The woodshop still produces Maloof’s original designs, led by master craftsman Mike Johnson, who has worked there for more than 30 years. Programs include educational offerings for all ages as well as an eclectic slate of changing exhibitions in a sleek, spacious gallery building. “Neo Native: Toward New Mythologies” (through January 7) presents work by contemporary artists of Native American descent. The show was curated by Tony Abeyta, whose father was a student of Alfreda Maloof in the 1930s when she was director of arts and crafts at the Santa Fe Indian School – another manifestation of the connections that characterize this special place.

Recently I revisited the foundation to meet with Jim Rawitsch, who came from a background in art, education, and historic preservation to join the Maloof as executive director in 2012. He spoke of the challenge, and joy, of honoring and advancing the ethos of a towering figure in American craft.

What was Sam’s idea for the Maloof Foundation?

We were going through old board meeting minutes recently and came across a letter from Sam from 2006. In it, he spells out his vision for what the place should be: a museum, a learning place, and a center for the development of craftsmen.

Our challenge has been finding a path forward after the passing of the founding visionary, and remaining relevant and significant – not getting mired in the past, but using the past as a foundation and platform for building the future.

He was so quintessentially Californian. Or at least Californians love to claim him as our own.

That’s something we relate to a lot around here. Sam was born in California to immigrant parents from the Middle East and grew up at a time when the state was emerging as a huge, powerhouse economy and source of creativity and imagination – in aerospace, entertainment, and a lot of other areas. What was new was coming out of California. He embraced that world, and his work came to reflect that energy.

We like to remind people that the Maloof presence at that time puts him squarely in the midcentury period, both in terms of his ideas, his aesthetic, and his involvement in Los Angeles, which was a hotbed of experimentation in those days. People think of midcentury architecture as glass, steel, and chrome. Sam’s success had to do with something sculptural and aesthetic in the midst of hard surfaces, that gave humanity and comfort to a midcentury sensibility.

And warmth.

And warmth. Sam is also an important figure in terms of a transition in American craft. There’s been a lot of talk about traditional craft and what informed making until a certain time in the 20th century, when a new [post-World War II] generation reimagined craft and made it their own, and it became quite contemporary.

Now we see an opportunity to reimagine what craft means to the 21st century and another new generation of makers. When it comes to that idea of making we all talk about these days – about how you create, use materials, share your vision, live your life – Maloof was ahead of the curve.

The idea of preservation to the point of never changing doesn’t seem to apply here.

We’re part of the Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios program, established by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. It’s a network of about 40 homes around the country. What makes the Maloof different is that many homes – particularly those of 19th-century artists – are collected long after the artists are gone. Because the Maloof was collected while Sam was still alive, we don’t have to reproduce anything. So the life you see is the life he lived. It has a kind of integrity and tells a story in its authenticity.

In carrying the place forward, we do work in education and exhibitions, we publish books and catalogues. The idea is to keep the spirit of the place very much in the present tense. It’s important that people not think of this historic home as a shrine or mausoleum. It has lessons to teach today.

The Maloof was also an early adapter of water-wise landscape design. Now, of course, that’s a feature of every other front lawn in Southern California.

Always ahead of our time! The journey started with Sam and Alfreda, who lived for 50 years in their home. Then plans were made to move the house. Alfreda did not survive to see it relocated, and Sam was distraught. A lot of people expected he wouldn’t survive the relocation project. But in fact, it became a new challenge for him. In grieving for Alfreda, he experienced the darkness, then sunlight at the end of the tunnel. The move became a part of that journey for him. He came out the other side with the house relocated and decided, “Yes, maybe there’s a life ahead of me.”

With newfound optimism, he married again. Beverly Maloof brought to the compound a history and sensibility with regard to horticulture and landscaping, and became an advocate for this water-wise garden, which got planted and now, years later, burgeons. It took imagination to envision what the growth would become. As we wander around, we see the place is even more of a paradise now than when Sam was alive. That, too, is a gift to the future: the world as a garden of possibilities.

That’s a real California story, isn’t it? The freeway displaces, only to open up new horizons.

In some ways, the freeway forced the thinking about the future of the house. It couldn’t just be demolished; something had to be done. Decisions were made in the process to determine the best outcome. And so the Maloof became a model for historic preservation, in addition to a model for a life in craft.

What’s ahead?

We’ve got a number of things we’re working on. Most important is the plan for what we’re calling the Maloof Center. It encompasses the creation of the Maloof Award, of nationally touring wood art exhibitions, of the Maloof Fellows program, to bring in that next generation of wood artists to learn from masters. We’ve received $150,000 from the Windgate Foundation to begin developing that plan. It requires further support and fundraising, but that’s the path we’re on now.

From the beginning, our mission has included nurturing artists. Sam, by his life, gave example to that. It was where he felt his legacy could make a difference. We focus on visitors who come to see the place, but the other constituency we serve is artists and craftsmen. We like to think we create an environment where craft is welcomed, encouraged, rewarded, celebrated, and made available and comprehensible to the broadest possible audience.