Conversation Starter

Conversation Starter

Bart Niswonger wanted to talk to people. That’s how it all started for the furniture maker, whose wildly colorful, off-kilter creations have won him fans, fellowships, and awards across the country. In the early 2000s, Niswonger was a grad student in computer science at the University of Washington, and though he loved his work, he found it isolating. “What drew me to computer science is that there’s real complexity; there’s these notions of design,” he says. “Notions of aesthetics, notions of elegance, they’re all there. But what you’re actually talking about, no one can see. ... The only person who could have a conversation about it at all was my advisor, and he really didn’t fully understand it. It was incredibly frustrating.”

Niswonger relieved that frustration by making furniture in his free time. (He had been building things out of wood since elementary school.) In furniture design, he found a natural parallel to computer science – both require a knack for pattern and precision – and says that applying those skills to something he could see and feel kept him sane. Eventually, the hobby overtook the putative vocation. “At some point I thought, ‘This is stupid. Why am I doing this thing I want to do [only] in the off-time?’ ”

So he did the only thing that made sense: After earning his master’s, he moved back to his hometown of Williamsburg, Massachusetts, and turned his attention to furniture full time.

The sense of relief was immediate. Not only did Niswonger keep the challenge and intellectual rigor of his previous field, but he also produced tangible work that led to real conversations. “At the end of the day,” he says happily, “I can talk to anybody about a piece of furniture.”

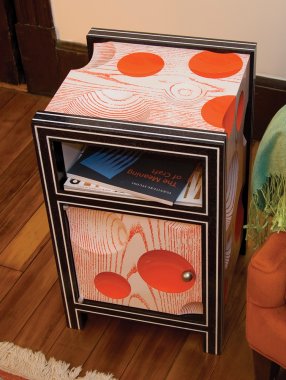

At 43, nearly two decades into his career as a maker, Niswonger builds furniture that draws the eye and defies expectation. There’s nothing plain or muted about it. Instead, there are chests of drawers that look like lacquered seaweed, citrus-tinged nightstands, amoeba-inflected bureaus. Straight edges turn ragged, and surprise openings appear in flat surfaces. And the color wheel is represented in all its glory. Bombastic reds, aquatic teals, summertime yellows – you’re much more likely to find any of these in a Niswonger piece than natural brown.

Color intrigued him from the start. One of the first things he made was a bed (“I needed something to sleep on when I moved to Seattle for grad school”), which he painted blue and yellow, with a green, yellow, and red table to go with it. What started as a way to compensate for cheap materials – Niswonger was using bargain two-by-fours in those days – became an obsession and a defining aspect of his art. “I got so tired of looking at furniture, going around and seeing what people were making, and it’s all either cherry or maple,” he says. “Surely there’s something else out there.”

When he talks about his experiments with color, he splits the difference between his scientific and artistic temperaments. “Light and color go together for me,” he says. “Cutting through pieces [of wood], or having undercuts with color, you start getting these funny glows.” The paints and dyes he applies to wood emphasize and exaggerate this natural effect. His F.O.M. Cabinet (2010) is all white on the outside, but holes reveal an illuminated interior painted Mercurochrome orange. “When you’re looking at it,” the artist explains, “you get this other color that you can’t see from the outside, necessarily. You get these spots that you wouldn’t expect.”

Niswonger is careful not to cover up his materials but, rather, to collaborate with them. “I get really interested in shifting color but not obscuring the wood,” he says. He sometimes sandblasts wood before painting it to make the grain stand out, and early in his career, he often used dyes instead of paints, so as not to overpower what was underneath. More recently, he’s taken to working on “a bunch of grain-fill stuff, where the grain is opened up in one way or another, and then the material, the wood, is dyed one color and the grain is filled with another.”

The move from computer science to furniture making wasn’t the only overhaul in Niswonger’s life. Eight years ago, he and his wife, Eliza Lake, bought the farm she grew up on, and it has become, in the artist’s words, “quite its own little project.” Together, they raise cattle, pigs, and chickens, using some trees as material for furniture. They run the farm as a business, while raising their children, Augustus, 10, and Charlotte, 7.

Making the farm more self-sufficient – and giving himself more time in the studio – is an ongoing concern. “We don’t have cows escaping [anymore],” Niswonger said. “It used to be, ‘I’m going to go to the shop and do X, Y, and Z,’ and you walk out the door, and you’re like, ‘Oh, the cows are all out.’ ” On a practical level, finding time to work can present a challenge. “It’s farm, furniture, and family, or furniture, family, and farm, or – it depends on the week,” the furniture maker says.

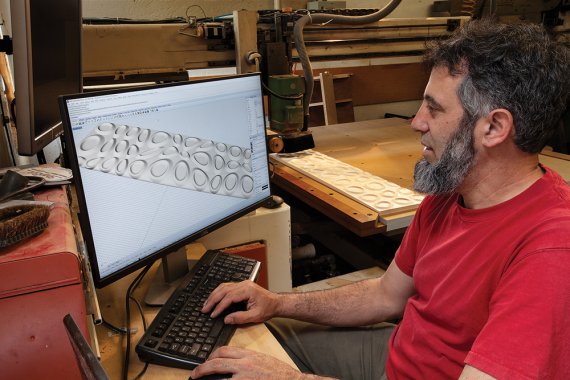

Niswonger has slowly been able to bring his onevtime passion for computer science into his artistic life. In 2011, he used some fellowship money to buy a CNC router, a computer-controlled woodworking tool, which he says let him start “accepting my computer past and incorporating it into the furniture.” Though the router is designed to produce immaculate, repeatable forms, he programs it to introduce randomness. When a customer requested an opening for a phone in an armoire, Niswonger instructed the CNC to make the opening a certain diameter but with uneven, arbitrary edges. Randomness is one way he finds to cut through the barrier of software that separates him from the wood: “I lay out the general framework; the computer fills in some of the details. Together we get an object that neither of us would have made on our own.”

For Irregular Mirrors (2018), he input directions for concentric rings with ridged edges but let the program decide what to turn out within those limitations. “I am amused by the irony of taking a CNC machine, which is really specifically designed for repetition and precision, and saying, ‘All right, we’re going to make one-offs on this thing,’ ” he says.

Those mirrors – no surprise – ended up painted translucent greens and yellows, so the grain of the wood shows through. Niswonger also painted rings of red on the back edges; though invisible from the front, the color glows against the walls where the mirrors hang.

That was the final touch on a process that he still finds invigorating and refreshing all these years later. “That’s interesting to me, that relationship between my action, which is extremely prescribed, and this organic tree that just grew up however it is. I don’t know what it’s going to look like until I cut into it, because I don’t know what the tree did.” When his pieces are finished, a trace of that mystery lingers – but he can point to it, touch it, and talk about it with anyone who’s interested.