Craft Without Boundaries

Craft Without Boundaries

Stephen Burks designed Islands, 2019, a large wood and marble cabinet that was manufactured by Italy’s Living Divani. Photo by Joe Coscia.

Broom Thing, 2020, is made from mixed materials. It was designed by Burks and manufactured by Stephen Burks Man Made and Berea College Student Crafts. Photo by Justin Skeens.

Brooklyn, New York–based Stephen Burks was the first African American industrial designer to break into the world of high-end manufacturers, working for some of the biggest names, including Roche Bobois and Missoni. But he has also developed strong ties with communities of craft artists in Africa, Southeast Asia, and elsewhere, and found ways to infuse his design ideas with their inherited craft wisdom, while challenging them to see their work afresh.

Shelter in Place is a mulitfaceted exploration of Burks’s 20-year design career, including work for major manufacturers, works developed with students at Berea College in Kentucky, and a commissioned series of experimental pieces that fuse design and craft in unpredictable ways.

The project began with lockdown-period conversations between the designer and the museum’s curator of decorative arts and design, Monica Obniski. “We thought, let’s do a show highlighting key projects over time,” she says. “But then let’s also create projects that are more experimental, speculative, or just kooky.”

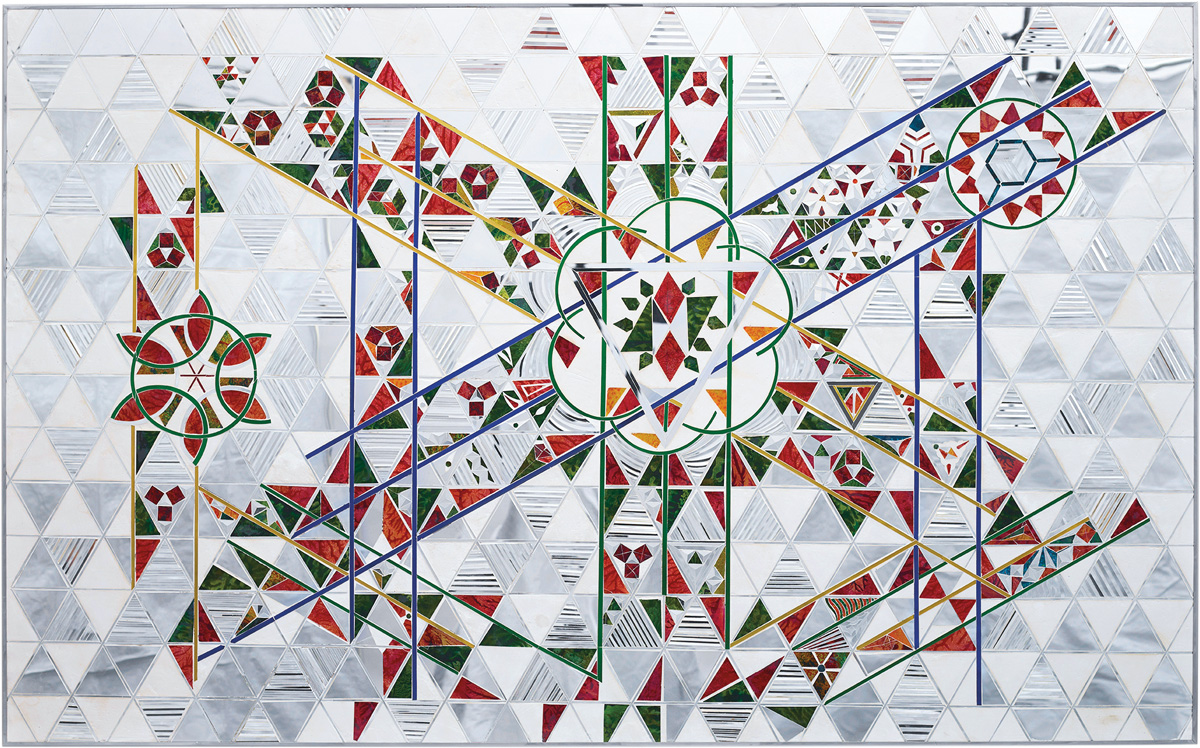

ABOVE: Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian composed Gabbeh, 2009, from mirror, reverse-painted glass, and plaster on wood. Photo by Robert Divers Herrick, courtesy of the estate of the artist and Haines Gallery. © Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian. LEFT: Farmanfarmaian’s Second Family: Hexagon, 2011.” Photo courtesy of the estate of the artist and Haines Gallery. © Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian.

The result is a wide-ranging view of a designer committed to the widening of design horizons and the centrality of craft. “I want to show what Stephen’s practice looks like,” says Obniski, “because he’s been designing for over 20 years and not very many people know who he is. And I hope that his collaborative method shows a way of future-making.”

A retrospective of works by Monir Farmanfarmaian (1922–2019) at the High Museum, A Mirror Garden celebrates an artist who overcame gender barriers to play a leading role in bringing postwar modernism into Iranian art. During 12 years in New York (1945–1957), Farmanfarmaian absorbed the forms and patterns of abstract expressionism. But her complex, luminous sculptures, intricate and mathematically rigorous, also employ the techniques of traditional Iranian mirror mosaics and reverse painting on glass—craft forms of which she was an avid collector and advocate.

“It was foundational for her to preserve the craft traditions of Iran,” says Michael Rooks, the High’s curator of modern and contemporary art and organizer of the retrospective. “Her career is a love letter to the idea of craft.”

Rooks connects the artist’s mastery of mirror mosaic technique with a profound vision of reality. “The mirrors in these works,” he says, “aren’t reflecting the face of the viewer. They’re actually reflecting themselves, and in that sense, they’re creating an idea of infinity—it’s abstraction that comes out of centuries-old craft traditions.”

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.