Deep Roots

Deep Roots

Tucked away on a wooded hillside just off the bustling main strip of downtown Gatlinburg, Tennessee, the Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts is a serene campus of old and new buildings on 13 green acres, where people from all over come for world-class handwork instruction, and more.

“I tell them, if they’re looking for an artistic retreat, they can just let our studios, porches, gathering areas, library, and galleries be their environment. If they want to see a bear and a waterfall before breakfast, that’s five minutes away,” says Bill May, executive director of the school, which sits on the edge of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. “And if they want to go taste some moonshine and get a bottle of aspirin afterward, there’s a drugstore within walking distance,” he jokes. “It’s a unique setting.”

Arrowmont’s roots run deep and wide through East Tennessee. In 1912, long before the region became a tourist mecca – more than 11 million flock there annually to camp, shop, and visit the Dollywood theme park – members of the Pi Beta Phi women’s fraternity arrived to establish a settlement school in what was one of the most impoverished places in Appalachia. Their philanthropy brought education and healthcare, while their development of craft cottage industries and workshops spurred a thriving arts and crafts economy. By 1968, the county had established its own public school system, and the Pi Beta Phi school became Arrowmont, a craft education center.

Yet, in the past decade, Arrowmont’s very existence was threatened by two disasters: a financial crisis, followed by massive, deadly wildfires that devastated the area. The school bounced back, thanks largely to the efforts of May, who, against the odds, twice rallied support to save it.

“Bill is the real deal,” says Anne Pope, executive director of the Tennessee Arts Commission. “He’s an articulate, visionary, and creative leader, who had the trust of the community, public officials, and national funders. He was the right person at the right time to lead the organization, ensuring that Arrowmont will continue to positively impact Tennessee and visual arts education for years to come.”

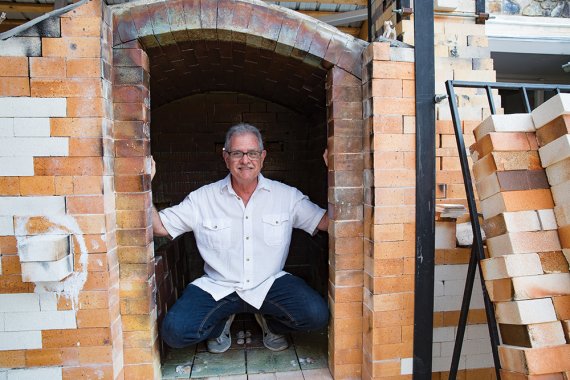

“At first glance, Bill might be perceived as quiet, unassuming, laid back, and he is all that. But when pursuing a goal, he is a most determined and committed individual,” says Frances Day, Arrowmont’s director of institutional advancement. Under May and his team of staff and supporters, the school has enjoyed unprecedented growth in enrollment, revenue, donations, and endowments. Beyond the numbers, its success can be measured by the variety of opportunities it offers: scholarships for teachers, returning soldiers, and students with financial need from all backgrounds; ArtReach, a program that hires artisans in central Appalachia to teach their skills to schoolchildren in their communities; the Windgate University Fellowship, enabling 140 college art students to take Arrowmont classes; and the Bill May Scholarship for Extra-Ordinary Artists, open to anyone following a creative path.

This spring, the school will celebrate two milestones – the 75th anniversary of its first summer craft workshop and the 50th of the completion of its main building – as well as wrap up an ambitious $30 million capital campaign. At 66, May is contemplating pursuing other projects, but first he’s set on securing Arrowmont’s future for generations to come.

Arrowmont is close to your heart. What, for you, is the magic of the place?

I think it has to do with history. I get asked a lot, was Arrowmont here before Dolly Parton? I have to remind people, it was here as a school before Dolly Parton’s father was born!

We’re in a location that has been rich in craft for a long time. Early on it was basic, utilitarian. People made blankets, quilts, baskets, chairs. The chairs, as they say around here, were settin’ chairs. Baskets were for gathering eggs, apples, vegetables from the garden. Most everything was done on a barter basis – you know, I’ll grind your corn and you give me a jug of moonshine.

The Pi Beta Phi teachers recognized these crafts, and helped develop a cottage weaving industry. This brought in some of the very first cash to the area – and what’s interesting is, it was women who had it. There’s this story told of a weaver who wanted a bigger loom. Her husband said, “Well, I don’t see how we’re going to do that.” She reached into her pocket, pulled out a big roll of bills and said: “I can buy it. I’ve made the money.”

The school is grounded in history and tradition, yet also embraces modern approaches to craft.

We have objects in our permanent collection dating back to the turn of the century. But things change. At one time a basket was for carrying eggs; now it might be a metaphorical basket that carries ideas. We’ve got one from the early 1900s by Aunt Liddy [Lydia Whaley], who sat and made baskets while she smoked a pipe on her porch; I keep her portrait here in the office. Then you have someone like Nathalie Miebach [a contemporary sculptor who uses the basket as a conceptual form]. That tells you how things evolve.

What brought you to the area and the school?

I grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, studied English and psychology at Tulane University, and then taught high school English, but it wasn’t something I wanted to do forever. I had visited this area my whole life, had come as a Boy Scout to hike and camp in the national park. I thought it was the most beautiful place I had ever seen. So in 1980 I bought 16 acres outside of Gatlinburg – woods, a pond, a creek, a wonderful barn. I got a vintage Airstream travel trailer, moved it onto the property, and basically lived in it for the next 7½ years while I designed and built a passive solar house, where I still live.

Have you always been artistic?

When I was building the house, I got interested in art glass. I apprenticed in a stained-glass studio and worked there for almost 10 years, becoming head of production. I was getting hands-on instruction and experience, but wanted to shore that up. Somebody said, there’s this school called Arrowmont, and it was eight miles from my house.

So I came here as a student, 35 years ago. I remember sitting in the auditorium during orientation. I looked around and thought, “What am I doing here? I’m this English teacher. Everyone here but me is an artist, I’m just sure of it.” I’ve learned a lot since then. People come with a great variety of expectations and needs, seeking different outcomes.

I took drawing, painting, stone carving, and glass. In 1993, I opened my own stained-glass studio in the barn on my property, doing architectural commissions.

May started teaching at Arrowmont in the late ’90s as he and his wife, Anne, a concert pianist, raised their daughter and son. In 2009, four years after beating colon cancer, May joined the board, feeling “a need to give back.” Asked to fill in as interim director for six months, he ended up taking on the job for good, and phased out his glass business. Right away he faced a dire situation. In 2008, Pi Beta Phi had changed its philanthropic focus and withdrawn all funding from the school. Then in 2011, the fraternity decided to sell the property. Arrowmont was given less than eight months to raise the $8 million asking price, or close its doors.

How do you begin to deal with that kind of challenge?

One thing that served me well was a certain naïveté. I really believed Arrowmont could not go away. Too many people had been impacted by the school. This town knew Arrowmont was central to its identity.

I sat down with a piece of paper and brainstormed all the people and groups I thought had a vested interest in its survival – students, craftspeople, preservationists, environmentalists, people with historical connections to the school. I reached out to the government, and to foundations, in particular the Windgate Foundation [which funds contemporary craft and the visual arts]. Gatlinburg, a city of approximately 4,200 full-time residents, stepped up in a huge way and passed a $3.5 million bond issue. The county contributed three quarters of a million. Then about 360 individuals came together to make contributions.

On April 2, 2014, Arrowmont bought the property, free and clear, for $8 million. By then we were operating with a balanced budget, our enrollment was going up. Word began to get out that Arrowmont was a completely independent organization, financially sound, not going anywhere. We were saved.

But then…

Then, in November 2016, out of the mountains came a perfect storm with sustained 90-miles-per-hour winds. Fire hopped from ridgetop to ridgetop, then electrical lines began to go down. Suddenly the county, and the town of Gatlinburg, was an inferno. Fourteen people lost their lives.

On the day it began to encroach, my wife and I were on campus with volunteers, receiving artwork for our Sevier County biennial exhibition. We had our artists in residence here. It happened very quickly. We looked up, and fire was coming down the mountain.

What did you do?

I tried to stay calm, and in my best executive director tone said, “Well, go to your cars and load up your essentials.” I got a call from a friend in the park service, who said, “Hey, Bill. One, you need to get the hell out of there. Two, the parkway is on fire and it’s closed.” We got everyone in cars, and Anne led them out the back way.

I was here by myself. I got hoses and tried to water down some of the buildings. I went into our permanent collection closet and looked at the shelves. I would pick up a piece that was particularly meaningful to me, or of historic value, and set it down. Then I’d pick another. Pretty soon I had all these pieces on the floor and realized it was pointless. I started crying, because there wasn’t any saving it this way. If the fire came, it could take the whole campus.

Then I noticed a glow up on the far end of the campus, and found our maintenance shed and two dormitories on fire. I knew if it spread, that would be it. So I drove off campus, found a fire unit a block away, got out, and said, “Arrowmont is in flames, please come!” I jumped back in my car and they followed, sirens roaring. They couldn’t save the buildings already engulfed, but they were able to wet down some ground, give us a break. At the same time, the wind subsided, and it began to rain.

The two dorms and the shed had burned to the ground. But the fire had stopped within feet of our historic Red Barn dorm and our artist-in-residence studio. Later, I drove in through the smoke – still horrendous – and took video of the buildings as my headlights hit them: “Main building – still stands. Pottery studio – still stands. Woodshop – still stands.”

We had survived.

The outpouring of concern, support, and love for this institution was truly overwhelming. I immediately said, we’ll rebuild the dormitories even better, which we’ve done. We built a new campus entrance. We took the challenge as an opportunity.

What lessons did you learn from overcoming adversity?

For me, it confirmed that you have to discover ways you can serve, and therefore be appreciated by, your community.

After the fires, it was right before the holiday season. People had suffered this terrible loss. The town was still full of first responders and people clearing debris, helping with the recovery. We looked at our assets. We had a cafeteria, so we served lunches to anyone who wanted one. We opened our studios to local artists who were displaced. We were able to work with CERF+ [the emergency relief fund for craft artists] to secure grants for artists who had lost their studios. We served Christmas dinner for the community. We had a holiday guitar concert that was one of the first events after the fires where people were able to gather, hug each other, and tell their stories. It was very emotional.

It’s important to me that Arrowmont be respected nationally, even internationally, in the larger craft community. But it’s just as important that we be valued and loved by our local community. I think you can do both.

So what’s on the horizon?

We’re on the tail end of a comprehensive capital campaign called Moving Mountains; to me the bottom line is “Arrowmont forever.” The creative experience I had as a student, I want for as many people as possible. I’d like to think that 100 years in the future, that opportunity for personal and artistic growth will still be here, in perpetuity, never threatened again.

I want this to be a safe, welcoming, encouraging place for people of all backgrounds, ages, ethnicities, orientations. When they come here, they’re engaged in a common activity, using their hands, doing it together. There’s a camaraderie that develops, a level of communication and respect. And when have we ever needed that more, among people who otherwise have differences?