The Depths of Simplicity

The Depths of Simplicity

Representing a human being in the abstract, Yuri Kobayashi’s Believing, 2009, 74 x 74 x 20 in., stands on its own without a dab of glue. Photo by Craig Smith.

By spring, Kobayashi had created Believing (2009), a wheel-like sculpture 74 inches in diameter, with some four dozen sterling silver pins, and not a single dab of glue, holding together a structure of ash ribs and hundreds of half laps. The work represents a human being in the abstract, echoing da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. It was all but born in snow.

The observer can’t help but notice that Believing consists of countless pieces put together by hand, element by element, joint by joint. For the sculpture Passage II (2006), part of Kobayashi’s graduate thesis, she cut nearly 4,000 mortise and tenon joints and gathered them into a bridge of sorts, 17 feet long. Where Believing presents an organic whole that almost obscures the discipline required to make it, Passage II shows itself as a feat of endurance as well as vision, and is a little less comforting.

About that discipline and endurance: primed by early training in repetitive work in her native Japan, Kobayashi spends eight-hour days at the saw, with only a few breaks. During this cutting time she will play a song over and over again on repeat and make herself into a sort of woodworking engine. The song must be one she doesn’t understand. “Once I learn it in English,” she admitted to me, “the spell is broken, and I can’t listen to it while working ever again.”

Yuri Kobayashi in her studio at the Center for Furniture Craftsmanship. Photo by Bailey Davidson.

TOP: Vessel I, 2007, 5 x 60 x 9 in., is inspired by boats, which Kobayashi considers “the most romantic vehicles.” Photo by Jim Dugan. BOTTOM: A detail of Passage II, 2006, 72 x 204 x 18 in., constructed solely with mortise and tenon joints—nearly 4,000 of them. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Believing and Passage II reflect Kobayashi’s more expansive vision, her self-discipline, and her near tirelessness, but another example of early work presents a side of her that’s softer, more contemplative maybe, but no less startling and precise. Vessel I (2007) seems an object, functional as well as decorative, freed from a log, the way we hear that an artist working in stone frees the embedded, hidden subject from the rest of the material. Five feet long, it’s a wing of fir, hollowed out and fitted with a lid. What would be stored in it? Marbles? Pennies? Sea glass?

Not So Simple

Like any other highly accomplished craftsperson, Yuri Kobayashi evolves. But even as her work changes, there’s continuity in it: all of her pieces look both simple and complex, clear and deceptive. “Nothing I do is easy,” Kobayashi notes. “But the forms aren’t complicated.” It’s when the viewer looks more closely at the work, at the detail, that the full force of Kobayashi’s care, skill, and precision, but also a certain delicateness, strikes home.

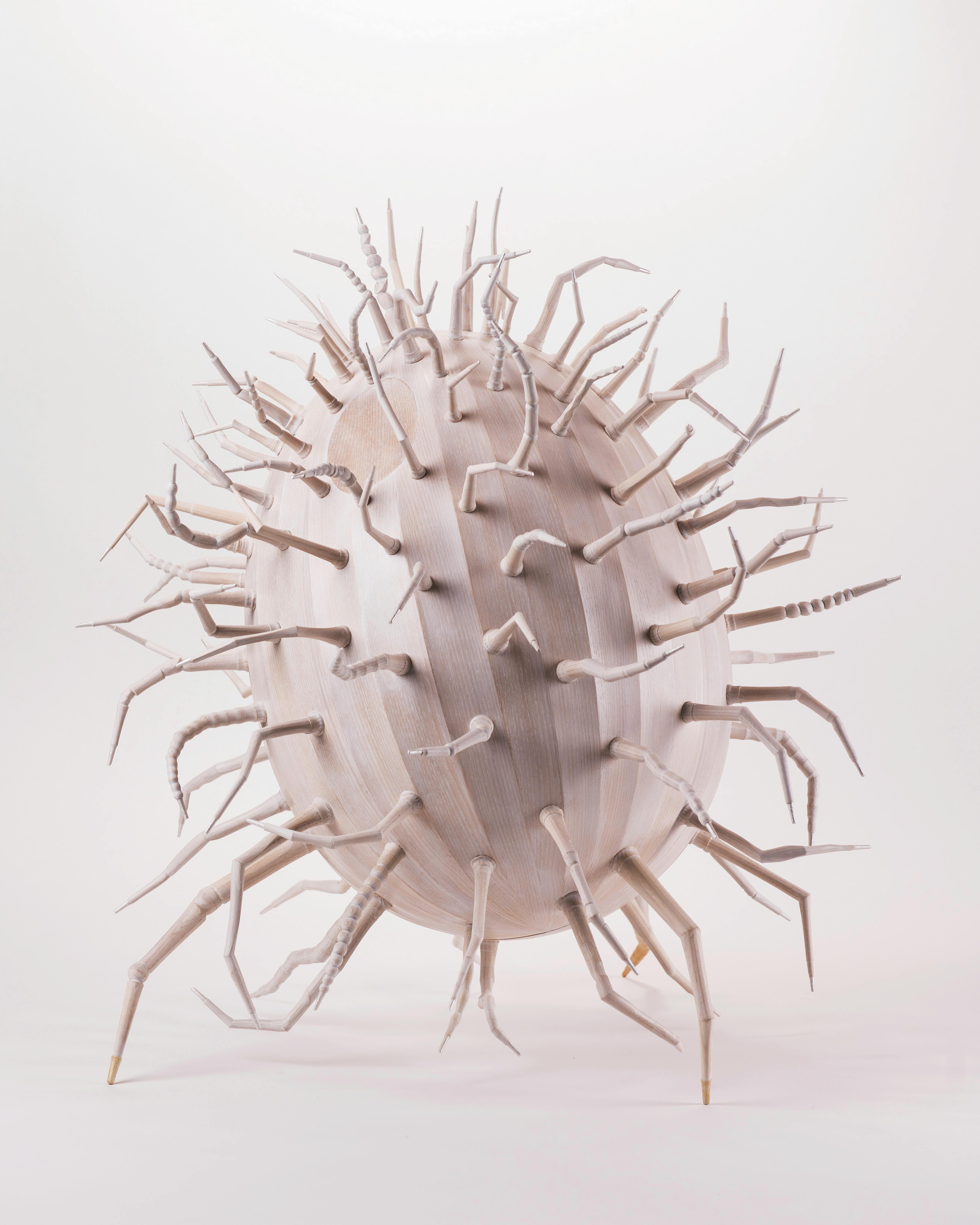

CURIO, 2015, 29 x 29 x 30 in., is a hollowed egg-like sculpture with over 100 turned and crooked spindles. Kobayashi says it represents negative thoughts and distractions coming from too many antennae. Photo by Dalton Paley.

“Every project has a problem to solve,” she told me.

I asked: “Is this how you learn new skills or approaches, trying to solve the problem of construction or form?”

“Yes,” she replied. “An answer might look easy, but it’s not.”

On the issue of complexity-in-simplicity, I queried Kobayashi about why she uses single words, with their distilled, almost poetic effect, for the titles of her work.

“When I began,” she said, “I didn’t know English. I learned to communicate my feelings and thoughts in my work. The thoughts themselves are both simple and complicated, and yes, poetic.”

The Gifts of Bending

The bending of wood has become more prominent in her work in the past few years. Through bending, Kobayashi has found her way to sculptural and functional forms that blend the totally organic, seemingly spontaneous exploration of Vessel I with the more technically and physically challenging process represented by Believing and Passage II.

TOP: Woven III, 2014, 11 x 23 x 9 in., shows Kobayashi’s devotion to nature and the magic of craft. Photo by Mark Juliana. BOTTOM: Courage, 2010, 18 x 120 x 12 in., a sculpture suspended from the ceiling contains curves of varying lengths. Photo by Jason Ramey.

“Bending frees me up. I think less about right angles, but it’s all harder to control.”

—Yuri Kobayashi

Take, for example, the large-scale Courage (2010) or the smaller-scale Woven III (2014). The former, 9 feet in length, resembles a giant double pod, holding a million invisible seeds, or even, from another angle, a creature of the deep sea. The latter, less than 2 feet long, might be some curious natural thing lying still behind a fallen tree. We see in both the repetition of elements found in earlier work, but the curves and the ends of varied length—giving the impression of a rough bundle of sticks interrupted by craft and human skill—these make us feel the maker’s devotion not only to natural form but also to the magic within craft, one aspect of which is the manipulation of materials that don’t readily surrender. (Kobayashi uses bent wood for functional pieces as well as sculptural ones, by the way. In the Lin chair [2015], for example, all the parts, including stays and seat, are bent; there’s not a straight plane to be found, except where leg meets floor.)

TOP: With Breathe -i hear you-, a 2019 rocking chair, Kobayashi calls on herself and others to sit down and have a rest. BOTTOM LEFT and CENTER: A glass-topped side table, Triumvirate, 2017, 25 x 21 x 21 in., involves repetitive use of a simple bent form. BOTTOM RIGHT: The Sui sidetable, 2016, 27 x 16 x 16 in. Photos by Mark Juliana.

To bend wood requires trial and error, patience, time. Steaming softens the lignin and fibers, the muscles of the wood. Then, when softened, the length is fit to a form and clamped in multiple places. Hopefully, when released hours or a day later, it won’t have cracked or twisted. With luck, it will not have sprung back out of its new form too much either, which would make it unusable. “Bending frees me up,” Kobayashi says. “I think less about right angles, but it’s all harder to control.”

Lin, 2015, references Kobayashi’s “aspiring persona as a grown-up human being.” Photo by Timothy Hogan.

For Kobayashi, one project in particular, her first kinetic sculpture, represents a triumph. Made for a solo show at the Arizona State University Art Museum, Consonance (2018) blends all of her explorations into one motorized piece. If it were hanging in stasis, there would certainly be enough for the observer to admire: the shape, the myriad parts, the collected elegance. But for the maker, physical motion, the parts coming to life, represents a new direction for her craft.

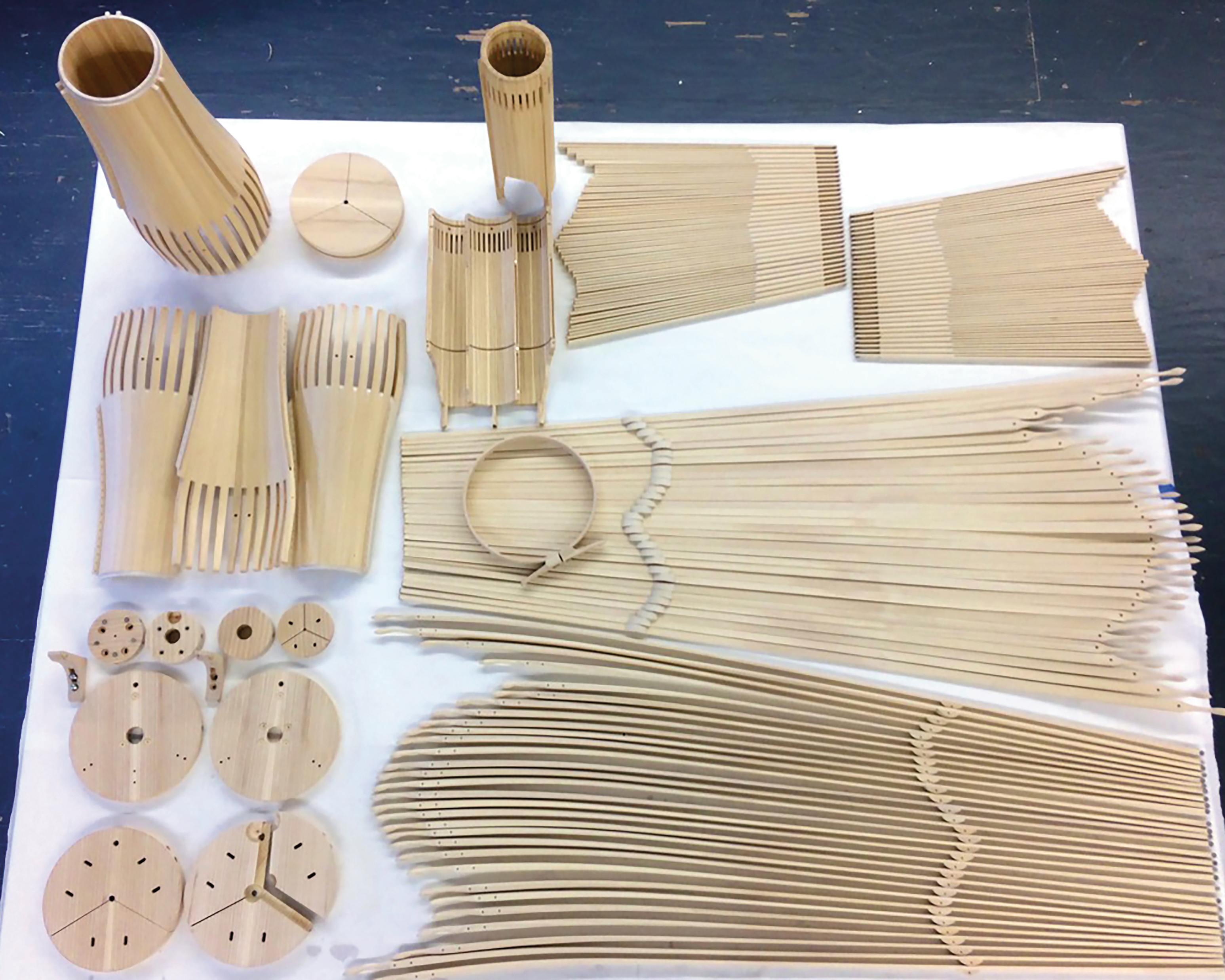

TOP: Consonance, 2018, 60 x 100 x 50 in., is a kinetic sculpture that moves slowly to soothing sound. BOTTOM LEFT: Consonance is made up of these small handcrafted components. Inspired by Leo Lionni’s children’s book Swimmy, Kobayashi’s work operates on the principle that many small parts working together can lead to meaningful and powerful outcomes. Photo courtesy of the atist. BOTTOM RIGHT: Detail of Consonance. Photo by Craig Smith.

Another thread runs through Kobayashi’s work across the years: her sense of time slipping away. The COVID pandemic, which kept her away from the shop for months, only reinforced this awareness. “I often think I won’t have enough time to make everything I can,” she told me. That’s a common thought in the minds of artists like Kobayashi, artists who need to work, whose lives and work are unified, and who pour all their vision and skill into craft.

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.