From Discarded To Maximized

From Discarded To Maximized

Upcycling artist Nicole McLaughlin sewed together used and sample Puma soccer-goalie gloves that would otherwise be discarded to make this jacket. Photo by Nicole McLaughlin.

Nicole McLaughlin is familiar with going viral. A recent outfit made from upcycled CamelBak water reservoirs drew close to 50K likes and effusive Dune references from commenters. She’s had more pieces meme-ified on the internet—where her cheeky humor is celebrated—than she can keep track of.

McLaughlin’s “wild and weird” work earned her a fast and devoted following (767K and counting on Instagram alone) and the role of first-ever design ambassador for the outdoor brand Arc’teryx. There she drives ReBird, the outfitter’s in-house upcycling program. Through her own work, and through a nonprofit workshop series that partners with big brands to donate their unused stock and samples for upcycling, McLaughlin has carved out an inspiring place in the sustainability conversation.

McLaughlin in her studio. Photo by Spencer Blake.

It’s no wonder that her fans include huge names like musician and tastemaker Pharrell Williams, all of them moved by her message to look at the everyday a little differently—and hopefully, McLaughlin says, to realize that trash can be a resource if you take the time to play. Here she offers ways to begin.

McLaughlin didn’t set out to make work that actively engages with the big idea of sustainability. “I was just making things. I didn’t know [then] that what I was doing was called ‘upcycling.’ I just saw potential in the material and wanted to explore that.”

TOP TO BOTTOM: Shower curtains and deadstock (unsellable) party favors reborn as pants. A bikini made from a Carhartt tool belt. A shoe made from beachballs; “This is functional and blows up,” says McLaughlin. Photos by Nicole McLaughlin.

The former graphic designer was an intern at a major athletic shoe company when she noticed the bins upon bins, every season, of unused samples from fabricators and factories. It didn’t sit well with McLaughlin that most of these design tests, by-products of the process that turns a designer’s idea into a real-life product, would ultimately be destroyed. Single shoes, drafts of jackets, and tested athletic gear would never see the inside of a store; all were fated for shredding and incineration or simply to be thrown out. It’s a fashion industry dirty not-so-secret. McLaughlin was intrigued to explore how those samples and other castoffs, as well as excess stock, could be reenvisioned.

Designing comes naturally for McLaughlin, but she says it took hours of trial and error, and deconstructing finished garments, to learn to technically execute her ideas for tongue-in-cheek, functional pieces.

“I started rummaging through those boxes [of samples],” McLaughlin says of her free time while interning at the athletic company. “I didn’t have a plan. I didn’t know how to make anything. But I saw value in these things. Taking them apart helped me understand construction, how things are made.” She started with hot glue and staples to put them back together in new ways (“Frankensteining,” she says with a laugh) and hasn’t really stopped. Not only did she learn about garment patterns and details like darts, but she says those first pieces were “a really good early exploration of shape and how things could have function.”

Every new material and project brings its own challenges, she says. A rock climber in her spare time, McLaughlin draws on the parallel of “problem-solving” in both climbing and design when faced with something new or unfamiliar. In climbing, she said on the Arc’teryx blog, “you don’t need to be in peak, tip-top shape to just go ahead and try it. Anyone with any body type can start climbing.” With time, you learn the unique advantages of your own body and experiences that you can draw on, she says. Which sounds a lot like how McLaughlin thinks about her upcycling practice.

Next on her list? Tackling woodworking and metallurgy.

One of the first pieces that McLaughlin felt was successful—she still remembers well—was a hooded vest made of bubble wrap. It was one of the first times that the idea of a garment pattern really clicked for her, she says. She used a hot glue gun to fuse the plastic seams.

“My process is fluid, [and] the materials really do what they want.” It’s important, she says, just “spending time with the material, and then figuring out the correct approach for it.” A lot of McLaughlin’s process is focused on “sculpting,” or “just wrapping a new material around my body, my foot, a chair—depending on what I’m making—to see what works.” The designer’s most-used tools are straight pins, like those used for sewing; they serve as temporary nails to keep the material in the new form that works best. That might mean aligning the zipper pockets of an old windbreaker over the top of a slipper, collaging half tennis balls into a beanie or oven mitt, or fusing packets of gummy bears into a utility vest.

“I didn’t know how to make anything. But I saw value in these things. Taking them apart helped me understand construction, how things are made.”

—Nicole McLaughlin

Mitten made from tennis balls. Photo by Nicole McLaughlin.

Everything McLaughlin sees has potential for creating something new. “Fleece, paper, food. I’m always asking: How I can maximize this? At a thrift store, I look for the thing that has the greatest amount of details to work with. Multiple pockets, reflectors, a great lining or logo. I may only need a hood for one thing, and the scraps go to something else.” Nothing is wasted, McLaughlin says. Even the tiniest leftover scraps that can’t be sewn into something can become stuffing for puffier pieces or pet toys.

But the key is to work quickly, by instinct. “The less I overthink it, the better it turns out,” she says. And if she does go a little too far? “Upcycling is very forgiving. You can overcut or patch something. No one will question if it’s weird.”

McLaughlin understands that conversations around sustainability and the future of fashion are a tough sell. “[Sustainability] is not an enjoyable topic at all, and it’s hard to get anyone to want to talk about it.” The general public can’t always relate, she says, because they don’t see the whole global supply chain that goes into making the thing they buy at the department store. It’s easier to turn a blind eye and continue to buy, accumulate, and eventually cast it all off. “[Our trash] ends up in a landfill, or exported to wind up on beaches halfway around the world,” she laments.

TOP: CamelBak water reservoirs, still functional, as a jacket. BOTTOM: The artist rescued damaged JanSport backpacks from the company’s warranty repair center and turned them into JanShorts. Photos by Nicole McLaughlin.

“I found that if you show it in a way that is more approachable, the conversation can start,” McLaughlin says. “That is the through line of my work: every piece is something that was discarded. People don’t always realize it because of the level of transformation, and I think it makes people look at things differently around their house.”

The sense of accomplishment McLaughlin felt with that first bubble-wrap vest is still there in her practice, but there is something really special, she says, about seeing others experience those early successes—to whatever extent that might be. Someone might come away from her workshops with sewing skills to hem their own pants or mend their family’s clothes. Another could eventually take upcycling to a level she hasn’t in her own work. A brand’s representatives might see what she’s done with their discarded backpack or jacket that’s gone viral and understand the potential in an upcycling program.

This is one of the reasons McLaughlin is passionate about her workshop series, and about growing her nonprofit to collaborate with more brands to donate their samples and unsold garments. The more of us who take a small step, McLaughlin asserts, the bigger the move we can make—together.

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

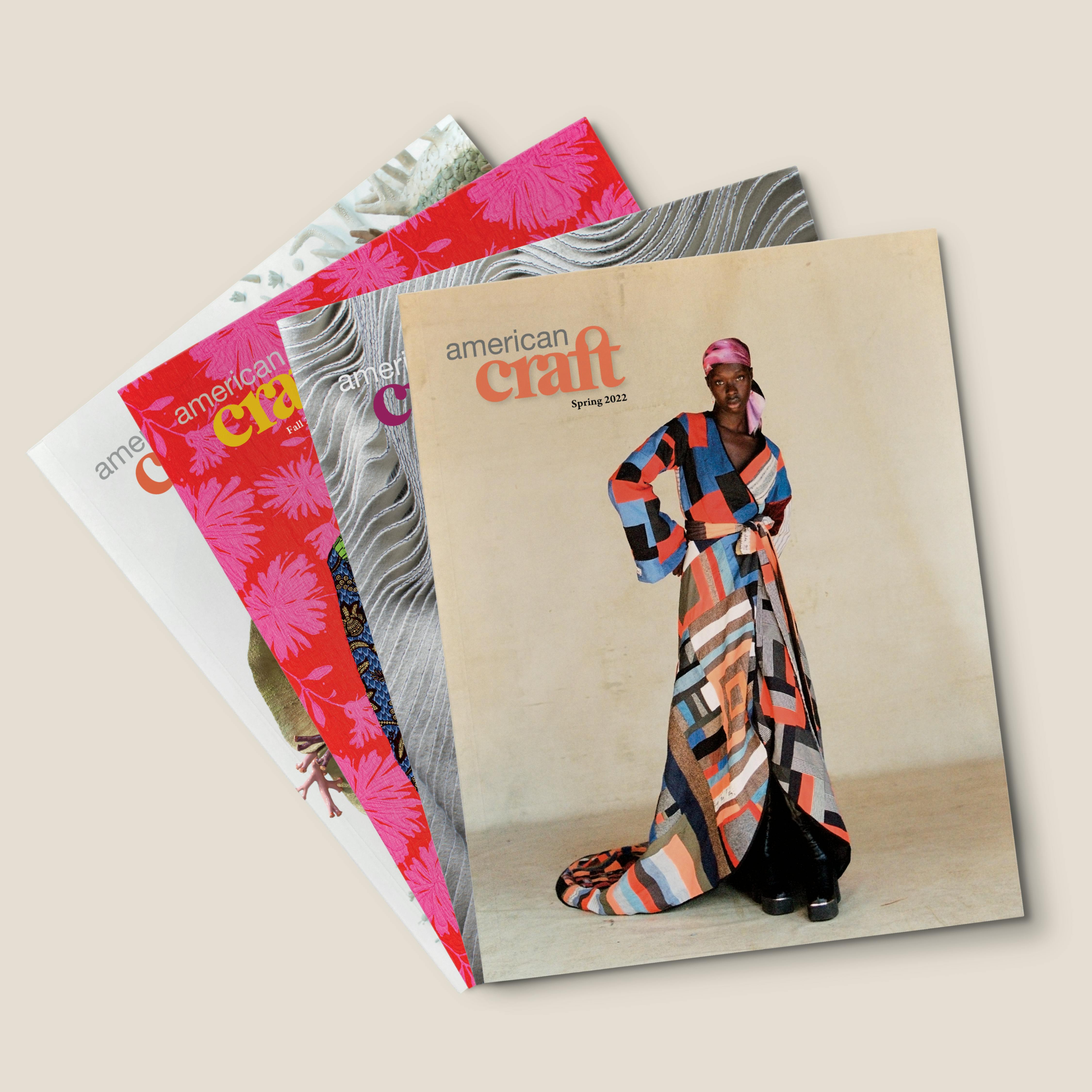

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.