Drawing Plans

Drawing Plans

Tough decisions and patience laid the foundation of Ayn Hanna's success as a textile artist.

One morning last fall, a question popped into Ayn Hanna’s mind: “What do New York, Chicago, Minneapolis, and Connecticut all have in common?” A hint of disbelief comes through as she reveals the answer: Before the end of the year, exhibitions featuring her textile work would open in all four locations.

In describing her recent successes, the artist, 52, resembles an architect watching her blueprints taking physical shape – excited, but grounded in the knowledge of what it took to get here. The work began some 30 years ago with a pivotal decision in her junior year at Colorado State University. “I was sitting in my cell biology class, and I literally got up in the middle of the class,” Hanna recalls. “I walked across campus to the art department and said ‘I want to change majors.’ ”

Just like that, she went from pre-med to graphic design. It wasn’t that she hated math or science. It was that she could no longer deny her creative self, despite an aversion to the financial risk of an art career.

Hanna is no stranger to a precarious existence. Growing up in Kansas City, Missouri, she watched her single mother struggle during tough times. “Even though I loved art, loved to draw, and wanted to be an artist, I had decided by sixth grade that I was going to be a doctor,” she says. “Somewhere along the line I picked up these messages that art was not a viable career.”

So when Hanna finally got there, the art department felt like a homecoming. During her graphic design studies, she discovered printmaking, and after graduation she stayed at Colorado State, earning an MFA in printmaking and sculpture. After that, she took an internship at a Colorado etching studio; then a job with a master printmaker led her to Manhattan. She honed her printing and etching skills for three years before again finding herself facing an uncertain future.

“I’ll never forget it. I was standing on the corner of Broadway and Canal, and I had nothing but a dime and a subway token in my pocket,” she says. Faced with student debt and trying to make rent, she made another tough decision. She returned to Colorado and took a night shift soldering parts onto PC boards for Hewlett-Packard.

“I’m an artist, but I’m a realist,” Hanna says. “It was important to me to be fiscally responsible. So I put a plan in place at that time. It was building a runway to be able to really launch my art career in an effective way.” She climbed from production worker to corporate executive – a trajectory where her creative skills were an advantage.

“I was an artist in a sea of computer science engineers and technicians,” she says. “As I was able to show good results, I kept getting asked to take on tougher challenges and higher-level roles with more responsibility.”

Hanna managed to stay artistically engaged, regularly working on her art at her alma mater’s print studio and joining an artists’ book-making group. Then, about 10 years ago, an artist friend introduced Hanna to textiles. It was a medium she had never before considered, and it was something she could work on at home.

“I didn’t really have a studio at the time and the kind of equipment that I use today,” she says. “Working with fabrics and threads and things, it’s pretty easy to be able to do that in a room. It’s not messy.”

Now, a decade on, Hanna’s textile work has grown alongside her corporate career. She installed her dream studio in 2008: 1,500 square feet of well-lit working space, an etching press, and three stitching machines. It was a crucial investment, enabling her to keep up with increasing demand for her work both from galleries looking to feature her detailed stitched wall art – which she calls her “soul work” – and shops, which sell her popular hand-dyed pillows and scarves.

In 2014, Hanna started creating Personal Badges – small fabric squares featuring stitched drawings, the artifacts of her life story. Mad Scientist, with its microscope, harks back to her chemistry days, while Perseverance features an oversized needle in a haystack and calls to mind the deliberate pace of her artistic journey. Others are more specific; Self-Reliant is a celebration of her first car, a Volkswagen Bug she saved up for at 17.

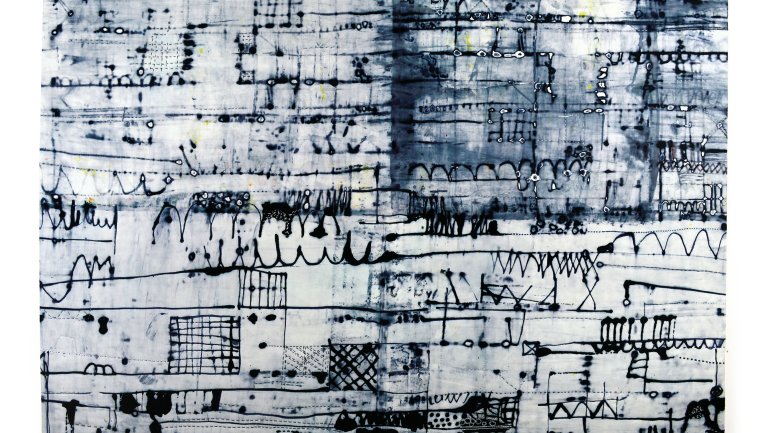

Her larger works can be equally personal. City Lines, a dye drawing that pays homage to her time in New York, exemplifies Hanna’s deliberate but flexible approach. The lines are confident but allow nature to take its course as the dye bleeds and thins; it’s Hanna as architect, drawing plans but accommodating the unpredictable.

“I really do believe that all of us are exactly where we need to be in this moment,” she says. Even though she sometimes feels overwhelmed by her demanding job and recently accelerated art career, Hanna’s patience, pragmatism, and faith in the long view prevail.

“It’s all really great stuff,” she says. “So I just have to drink a lot of water and get a lot of sleep and just remember that I’ve drawn this all here, and I have a lot of gratitude about all of it.”