A Floating World

A Floating World

Kristy Kún at work in a pool she constructed by placing a pond liner over a wood frame. Photo by Olivia McLeod.

Instructions for living a life:

Pay attention.

Be astonished.

Tell about it.

—Mary Oliver, “Sometimes”

Years later, I learned the basics of felt-making at my daughter’s elementary school, where we created balls and toys simply through the agitation of fibers in soap and water. Feeling a moistened bundle of fine wool slipping over the surface of my skin, gently tickling it with my fingertips and coaxing the fibers to tangle more closely—to form their own skin—felt magical.

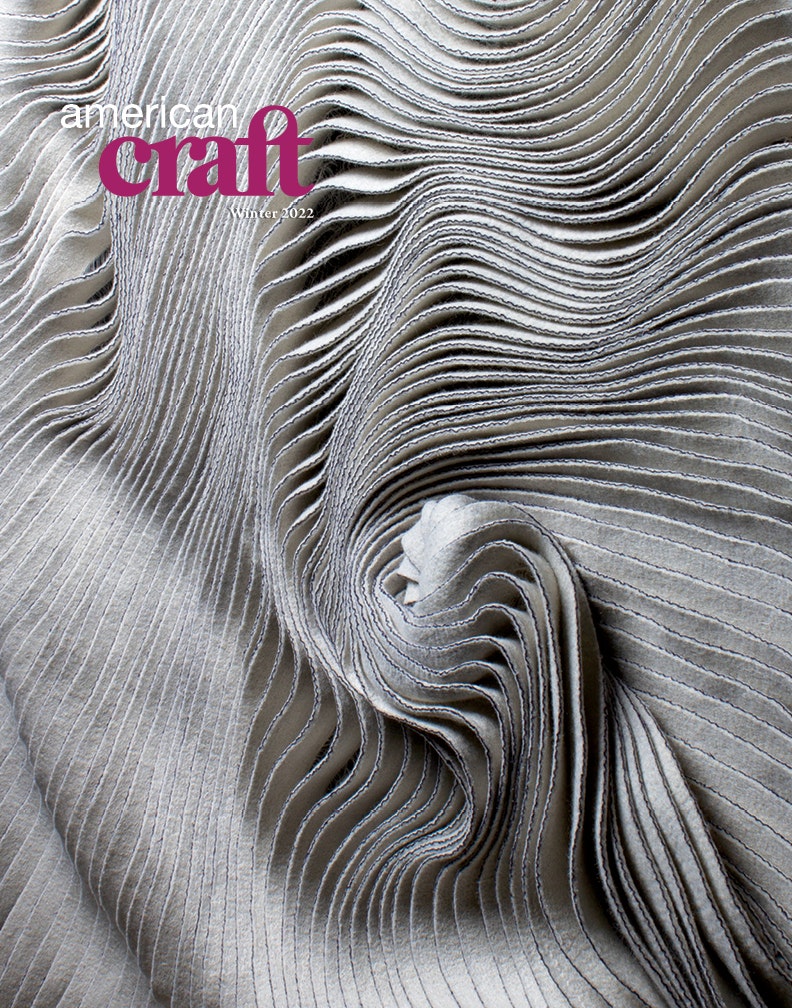

Measure of Retention, 2021, 78 x 36 x 4 in., a single sculpted piece of handmade felt. Photo by Kristy Kún.

When I create felt, my initial gesture of laying out wisps of wool fiber is as delicate as protecting a seeding dandelion from the warm summer wind. Then I wet the fibers and the felting begins. But just minutes into the process, as the fibers begin to tangle from my touching and the bundle begins to gain strength, I rub with much greater force, working deeply into the mass of the fibers. I work harder, with more soap and hotter water, squeezing and pressing the fibers into each other to finally entwine them into a firm, dense formation of felt.

The possibilities of working with this reactive material are endless. Tufts of wool can be worked into limitless sculptural forms; longer fibers spread into thin overlapping layers can be felted as textile sheets. Beyond techniques like creating dense forms and fabrics solely from wool, I can also coax the fibers through the weave of lightweight and sheer fabrics, creating new felted versions of woven structures. These novel structures retain their translucence, yet are reinforced with new textural strength and can be shaped and draped with more intention.

I’ve long been deeply moved by the transformative qualities of wool and plant fibers, which, when plied correctly, parallel environmental transformations: birth, fruition, decay.

For the first few years, I worked with felt to emulate the beauty I saw in wood. By pushing the limits of the fibers, I could in some way re-create in this new material some of what I was awed by in my previous medium. I created a number of personally developed methods—for instance, first needle-felting thick layers of drapery silk into the wool to engineer new kinds of constructions. The resulting patterns and glittering details were reminiscent of those radiant rays of the wood grain I sought when building furniture.

The more I explored, the larger and more complex the pieces became. Unconventional jigs (again, my builder brain pushing to engineer something new and never before seen) made way for layouts of heavy, sculptural ribs bonded to the lightest fabrics and threads: hemp, flax, cotton cheesecloth. The results were an innovation to the field of felting. The materials I was working with demanded I adapt both my studio and my physical process. I constructed larger and larger pools of water to float the complex wool layouts, adding buoyancy and relieving the weight and stress of the heavy, water-logged wool that I worked on for days and weeks.

Color of Wind, 2021, 27 x 21 x 6 in., was inspired by the autumn sky of southern Oregon. Photo by Kristy Kún.

In creating felt, I found a re-creating of myself. After leaving woodworking and the life that went with it, the loose fibers of my life slowly tangled together into a strong, resilient fabric; I built a new community, and a new life, among textile artists. In doing so, I also honored the values I had nurtured in the woodshop: working sustainably, with low-impact materials, and with methods that revealed the materials’ greatest potential. You could say I have slowly fallen in love with this gentle and quiet material.

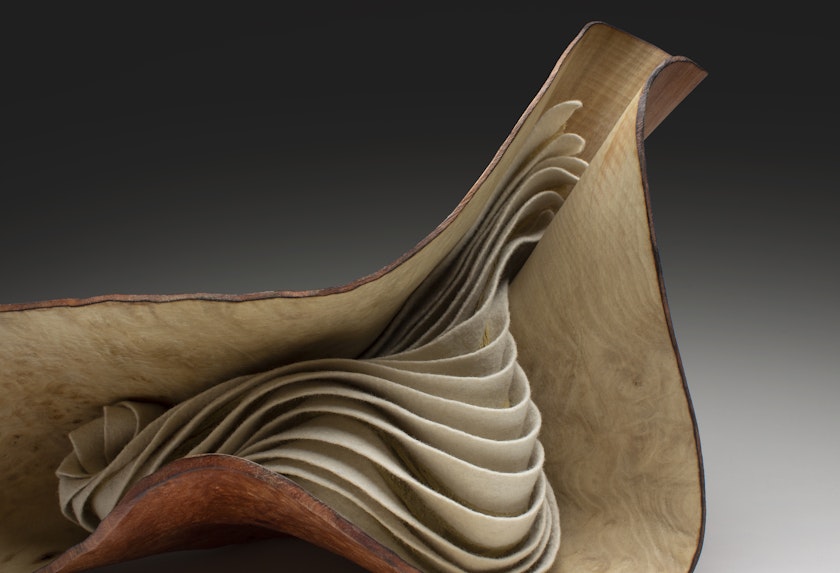

In the Current no. 3, 2020, 8 x 16 x 6 in., a felt sculpture mounted inside a madrone wood shell, is a collaboration between Kún and Christian Burchard. Photo by Kristy Kún.

And now, somehow, woodworking enters the scene again. My current projects include collaborative work, combining my felting with the woodwork of my partner, Christian Burchard. Christian works wood when it is green, so changes in the form and surface of the material are created through drying it in different ways. We have found that our treatment of materials blends and enhances the two mediums, inspiring viewers to consider how to preserve delicate ecosystems and how to hold them with reverence.

I’ve long been deeply moved by the transformative qualities of wool and plant fibers, which, when plied correctly, parallel environmental transformations: birth, fruition, decay. I strive to translate this energy from nature into new forms. In the later stages of the physically exhausting work of felting, naturally, I daydream—becoming lost in the mesmerizing transformation of the three-dimensional surfaces undulating in my hands. When I’m sculpting felt, formations of water, earth, and sky can emerge as if breathing. Free-flowing textures, forms evocative of shells, delicate ecosystems filtering light—full of alchemy and wonder . . . These are the places where I meditate.

I float the nearly finished project in front of me in a pond, letting it sink, watching it move like a living being. When the wool and silk hit the surface of the water, they break the reflection of the sun in patterns all their own. It’s like touching another world. I try to capture this flow and movement in the finished forms of my work, to keep the sensual and living magic of the fibers alive.

kristykun.com | @opulentfibers

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.