Free Form

Free Form

Christian Burchard approaches wood as he does life – with wild curiosity.

Christian Burchard has a way with wood, a gift for seeing and bringing out new dimensions of its natural beauty, the elemental poetry of rings and grain. He puts vision and skill into his expressive sculptures. But his masterstroke is letting the wood simply be.

“I’m in love with wood. What can I say? I’m in love with it,” is how the artist characterizes his passion of more than three decades. “This is the wildest material you possibly could use. Madrone, the trunk, the roots – it doesn’t get crazier than that.”

Burchard makes his home on a 7-acre “slice of heaven” surrounded by mountains and vineyards on the rural outskirts of Ashland, Oregon. There, for the past 17 years, he has worked almost exclusively with madrone, a tree species native to the region. He starts with a chain saw, cutting a hunk of wet, burly root into chunks. Working freehand with a band saw or a large saw mill, he cuts his simple, signature forms – thin panels to be arranged into wall compositions, open “books” with fluttering pages – then lets the pieces dry naturally or microwaves them. As moisture leaves the cells, the wood contracts, transforming into new, often surprising shapes. Once, Burchard cut a pair of panels in a way that turned them into classical human torsos so perfect they surprised even him. “I went, ‘Are you kidding me? Look at that!’ ”

Burchard’s process is a dance, so once the wood dries, he’ll retake the lead, “pull it back in, put my stamp on there.” He’ll sandblast the surfaces and bleach them white, revealing all sorts of detail and nuance, an effect he compares to going from color to black-and-white photography. “I want the viewer really to see what’s inside the wood – the power of it – without just looking at the glorious colors. I take the color out so you get the essence of a structure, its expressiveness.” He may add a final decorative touch, burn or carve a few primitive marks – mysterious, like tattoos or writing, but not. The end result is a collaboration – Burchard’s vision of what a piece of wood can be, and the wood’s willingness to go along. “My job is to see what’s there, and then to take it further.”

That balance – or battle – between control and freedom, predictability and serendipity, has been a theme throughout Burchard’s life. He was born in 1955 in Hamburg, Germany, to an old and prominent family. Despite his proper upbringing, in the late 1960s, like many young people, he was drawn to the counterculture, the zeitgeist of protest. His post-World War II generation, he recalls, was disaffected and angry, ashamed of being German, carrying “huge, unbelievable guilt for something we were not part of.” (As much as he tried to deny his nationality back then, today he laughingly admits that his American wife and kids “think I’m very German” because of the intensity of his craftsmanship and his emphasis on running a good business. Except for the odd, barely perceptible slip – he’ll talk of “verking” with wood, and quickly catch himself – he speaks perfect, unaccented English.)

At 18, he struck out for Australia – “as far away as I could get” – where he worked as a cowboy and for a mining company in the Outback. After a year Down Under, he hitchhiked through Asia, back to Hamburg. “It was a wonderful trip,” he recalls, “but I was never one to spend months on the beach in Goa, smoking my brains out.” In fact, he had a plan, albeit one that horrified his family. He wanted to work with his hands, rather than attend university for business or law. “It came out of protest, saying no to all of that,” he explains. “Also, it was something I could do and live anywhere. I wanted to travel.”

He nevertheless learned his craft the old-fashioned way, completing a traditional two-year apprenticeship in a furniture maker’s shop. It was an invaluable education – “you learned to understand material, wood technology, how to run a business" – and when it ended, he was ready to move on. “It’s pretty confined, a shop like that. Very German, very rigid. Again, it was, ‘Get me out of here!’ ”

He lived in Austria for a while, refinishing furniture, making toys and remodeling old houses. Around that time, he got into tai chi and in 1978 went to Colorado to study with a renowned teacher. One thing led to another in those freewheeling days: When he pondered studying art, a friend suggested the prestigious School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, so he applied and, to his surprise, got in. (“All my life I’ve been lucking out with these connections,” he muses, “and I still can’t tell you how they actually happened.”)

After touring the US and Canada in a Volkswagen bus, he went to Boston and spent 14-hour days devouring courses in everything from drawing and ceramics to metal sculpture and video art, never focusing on a specific degree. (“That wasn’t the point. I just wanted to learn.”) Next, at the Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver, Canada, he studied Northwest Coast Native American art and added toolmaking, forging, and metal casting to his repertoire.

It was woodworking, though, that came in handy in the early 1980s, when he married, settled in Ashland, and started a family. “Reality hit all of a sudden. How do you make a living doing art? Nobody teaches you that in art school. For years he did furniture, carpentry, timber framing, “whatever came along.” In the mid-’80s, he started making turned-wood objects and exhibiting them at fine craft galleries and shows. He had commercial success with a series of elegant vessels (“I made maybe 9,000 of those; that’s how I paid my bills”) before branching out to the more sculptural work he does now.

Today he remains that mix of solid citizen and free spirit. He’s deeply rooted in Ashland; when not in his woodshop, he’s tending his goats and sheep, or making cheese. Ever the curious adventurer, he recently traveled to Siberia to learn Tuvan throat singing at the source. His latest experimental pieces are still about the book, but larger, “not as literal, even quieter,” achieved with a few cuts. It’s a good life all around, says Burchard, who, in his search for the essence of wood, keeps finding the essence of himself.

“How lucky I am,” he marvels. “This fits me. I can go in the shop, talk to the pieces, trust my judgment. I’m not all over the place. That really is what comes after all these years, and then you’re able to put more depth into the work. But to have found – really, by mistake – something that fits! I’ve been very blessed.”

Joyce Lovelace is American Craft’s contributing editor.

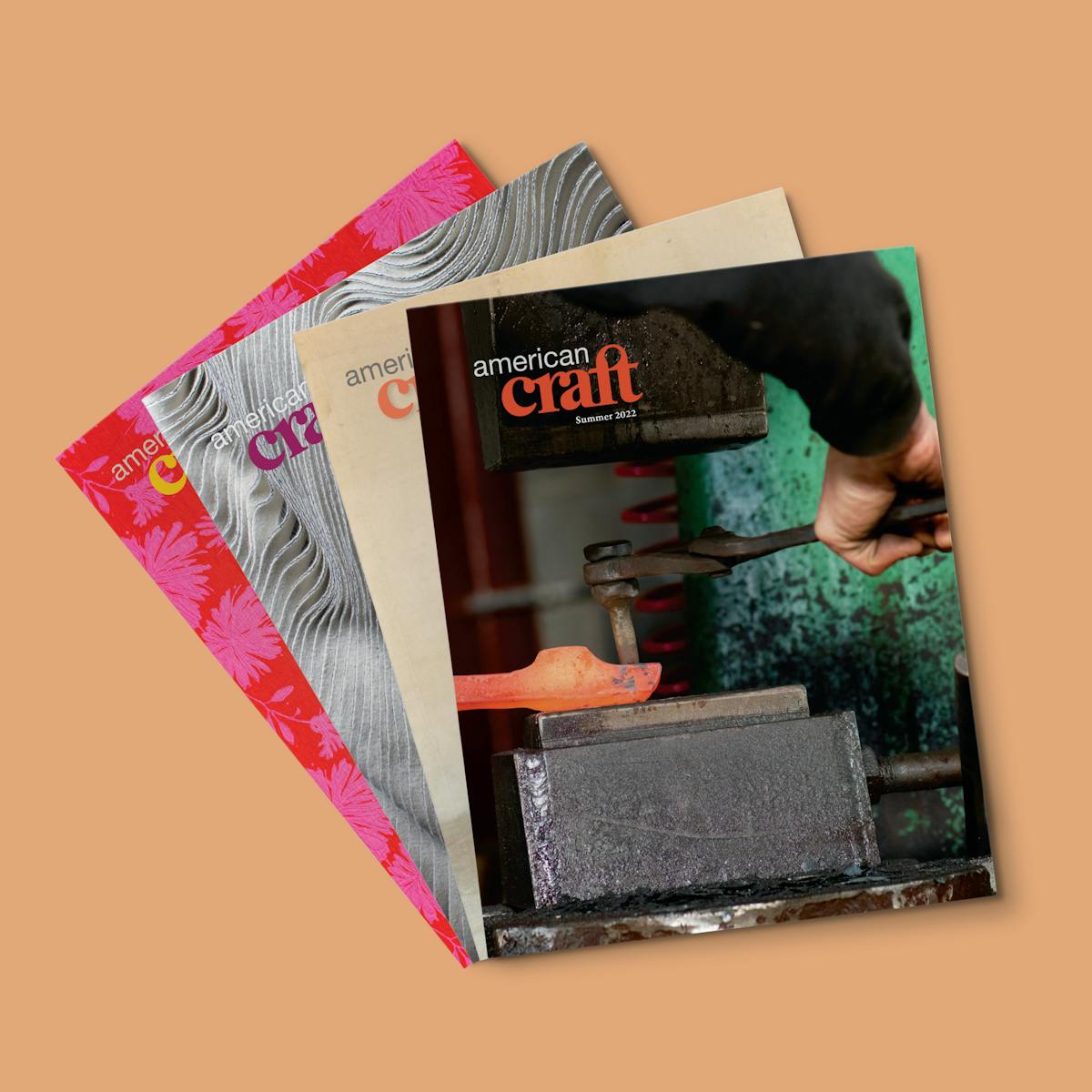

Discover More Inspiring Stories in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.