Funk and the Spirit

Funk and the Spirit

Photo by Jenna Bascom, courtesy of the Museum of Arts and Design.

Throughout her decades-long career, the artist, designer, cultural activist, and visual storyteller—perhaps best known for her vibrant and cosmic African-inspired headwear—has crocheted wall and floor mandalas, tents, and garments using her hands, four-ply yarns, and barrel-shaped plastic pony beads. Her work has evolved into major public installations that embody a design philosophy she calls “Paradise Under Reconstruction in the Aesthetic of Funk.”

Xenobia Bailey grew up with a “funky-chic urban household aesthetic” that informed her exploration of what she calls “funktion. Portrait by Daisy Chen, courtesy of Xenobia Bailey.

And what funk—which she remixes into “funktion”—means to Bailey is complex. Rooted in the ingenuity and sustainable practices of African American homemakers across time—including making do with what is at hand, creating vibrant beauty from humble materials, and facing hard times with resistance, faith, vigor, and energy—it cultivates a passionate spirit charged with uplifting emotional power. “This is a continuation of a non-commercialized craftiness, engineering, and design practice from rural and urban communities that gave birth to the funk, blues, and gospel music of the ’40s, ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s,” she says. “It’s a material culture that has a never-ending, germinating life cycle.”

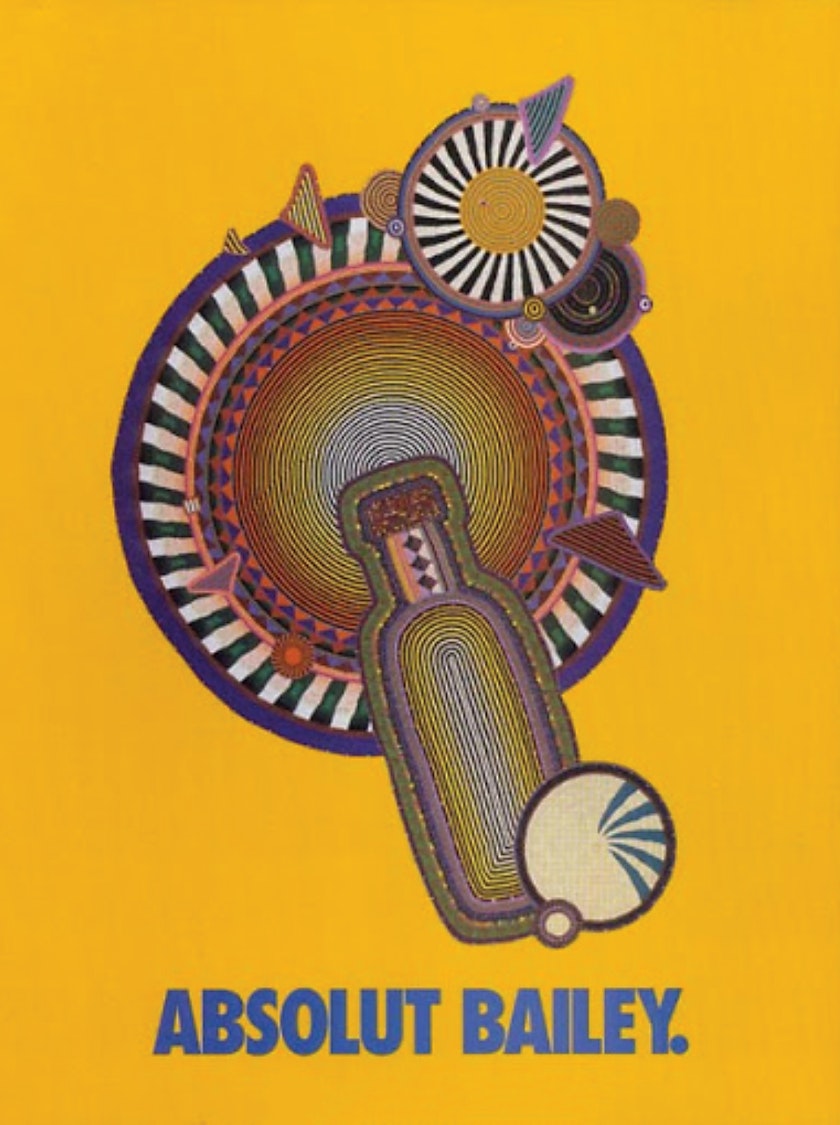

Bailey’s celebrated designs have shown up across pop culture, from TV to movies to this 2003 ad for Absolut vodka.

Her crochet mandalas start with “a simple primal shape: a circle” and flourish into tapestries of concentric circles and repeating geometric patterns that create vibrations on different visual frequencies. Often they’re embellished with plastic pony beads and glittering metallic filaments.

Some of her one-of-a-kind sculptural crowns are inspired by African headdresses, decorative hair braiding, and traditional design patterns and color affinities of different cultures. Throughout the 1980s, these crowns appeared all over: in Elle magazine, in Benetton and Absolut Vodka ad campaigns, on TV in The Cosby Show and A Different World, and in Spike Lee’s film Do the Right Thing.

After the workday, she returned to her apartment, where she created wooden toys and furniture for sale using exotic woods from around the world. But “sawing and sanding hardwoods in an apartment wasn’t healthy or easy,” she says. “I started searching for materials that were more conducive to my workspace.”

So she learned how to crochet from fellow CETA artist Bernadette Sonona, a needleworker whom Bailey describes as a master craftswoman. “Bernadette taught me everything I needed to know in just two days,” she says. “She taught a basic, free-form, fundamental type of crochet of comfortably holding the yarn with good tension as it moves through one’s fingers to make the desired stitches.” Bailey first learned the chain stitch and single stitch, then the double stitch, how to increase and decrease stitches, and how to change colors and create patterns. “I taught myself how to add beads,” she says.

“This is a continuation of a non-commercialized craftiness, engineering, and design practice from rural and urban communities that gave birth to the funk, blues, and gospel music of the ’40s, ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s.”

It was a technique that Bailey says “felt comfortable.” For her, crochet is “an intuitive human skill” based on “a system of knots” that is easily manipulated once you’ve learned the basics. Within days, she had learned all that she needed to in order to construct what she calls her “deferred material culture.”

Plus, the materials were highly accessible. “I just took a trip to the Woolworths variety store for yarn and a hook, and I was in business,” she says.

For Bailey, crochet is a therapeutic practice that has the power to heal. Photo by Jenna Bascom, courtesy of the Museum of Arts and Design.

Her home environment was filled with functional, decorative objects constructed from humble materials. Unable to find or afford an African American presence in the popular ceramic figurines and sculptural home decor of the time, Bailey’s mother instead graced the space with her own hands. “My mother and the women in my community created from found objects,” she says. “When I was a child, she made flower arrangements from newspapers and Better Homes & Gardens magazines because of the colorful pages.” She also created their clothing, curtains, and furniture cushions using mismatched textiles. “It was a funky-chic urban household aesthetic,” Bailey says. “It brought a special kind of energy to our home."

Many rural and some urban African American households applied sustainable “upcycling” long before the practice went mainstream, she points out. Bailey pays homage to this history in another aspect of her “aesthetic of funk” today by repurposing newspapers, grocery store flyers, advertising posters, and cardboard boxes with colorful advertisements into furnished art installations. “I take trash, and I give it value,” she says. “We can create currency from anything we apply our creativity to.”

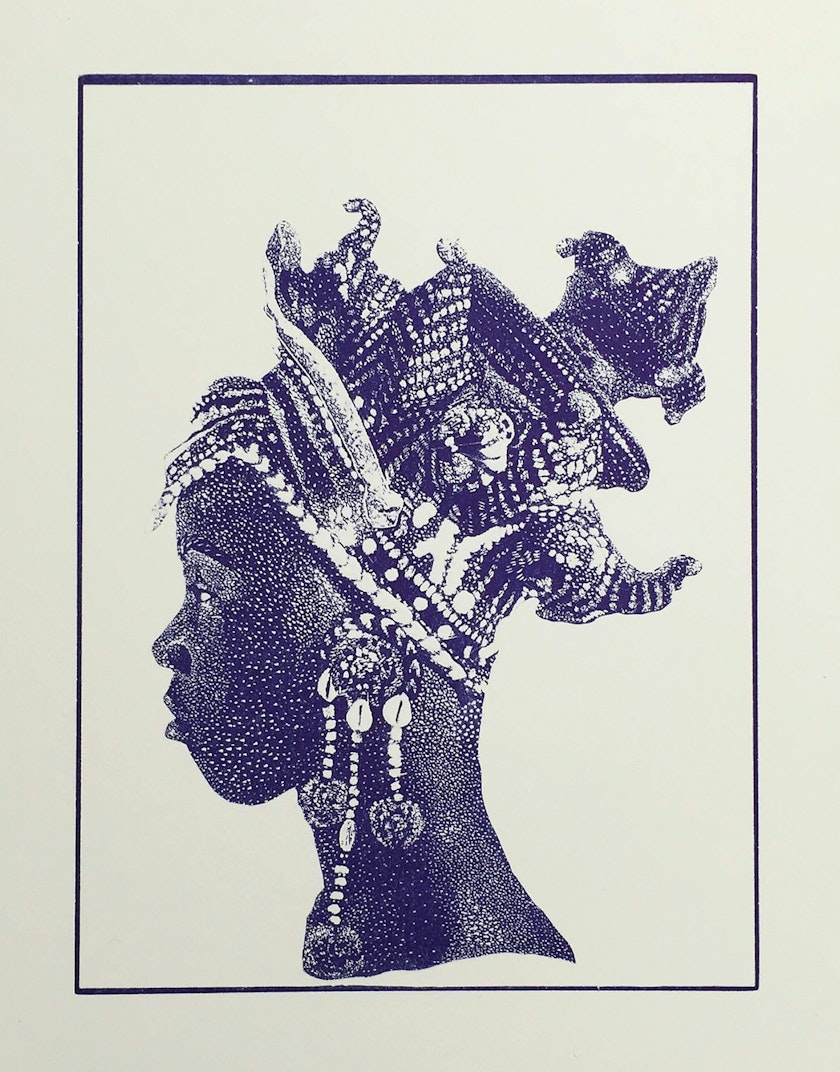

Urban Mystic #2, a 2016 limited-edition print by Bailey of one of her sculptural crowns.

Her desire to expand her knowledge of the African American design sensibility and its history was the major impetus for her studies at Pratt. “I knew there were commercial African American potters, weavers, metalsmiths, carpenters, engineers, and designers who designed and fabricated automobiles, boats, and other domestic power tools and equipment,” Bailey says. But “the official American history of the industrial revolution implies there was no such African American design population.”

Faced with this Euro–American and Eurocentric view of design and design history, she knew that although it was isolated, skilled industrial design was practiced in the African American population—she just had to locate it.

At Pratt, she learned how to work with forms, shapes, textures, color, and other facets, but always had to adjust them to communicate her emotional needs. “My natural sensibility of color differed from the industrialized manufactured palette, which didn’t move me,” she says. “I felt no energy with the mainstream system of color. I do not have the European sensitivity needed to utilize a European-American [design] aesthetic,” Bailey explains. Not wanting to surrender her principles, she dropped out of the industrial design program and transferred to an individualized program within the same school. But the industrial design chairman convinced Bailey to return by working with her to customize the program to fit her needs, and she pursued the research and study of African American design and material culture. Her thesis, “The African American Aesthetic of Interiors: Wooden Furniture and Wooden Toys,” was a culmination of that study.

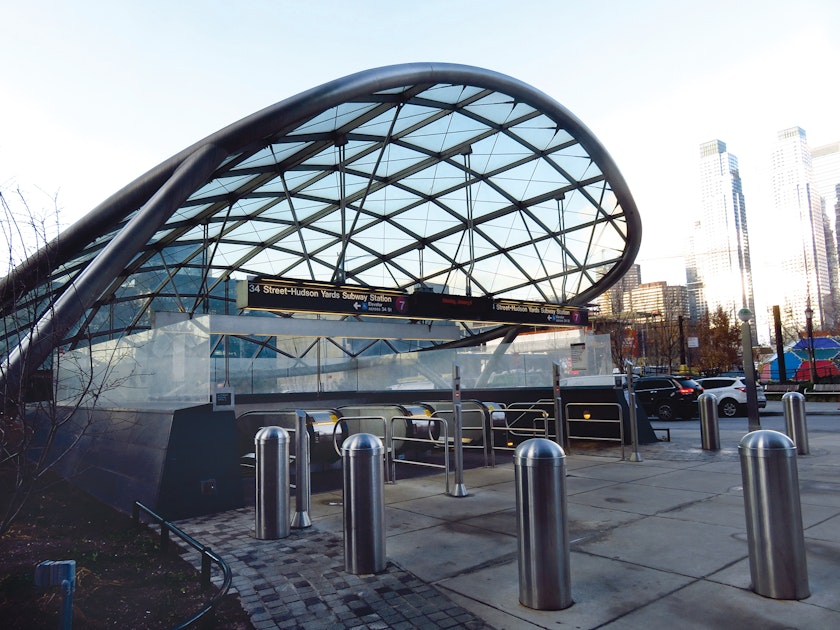

Bailey translated her mandalas into mosaics for Funktional Vibrations (2015) in New York City’s 34th Street Hudson Yards transit station. Photos by Paulette Young.

In 2018, Bailey was selected to create an installation for the grand reading room of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in Washington, DC. The large undertaking is scheduled to open early this fall. Her design incorporates a mystical ceiling with symbols from the Farmers’ Almanac and abstracted cosmic elements to guide African American homemakers, caregivers, domestic workers, and other cultural practitioners. She’s also crocheted large mandalas out of multicolored, 26-gauge copper wire, a challenging but satisfying task. “Copper wire is a conductor of energy,” she says. “The piece looks like a suspended electrical power plant, conducting energy for those studying in the reading room.”

She notes that the healing aspects of her art are meant to reach beyond herself. “The transatlantic enslavement of Africans created deep trauma that has been passed down through generations by environmental degradation, police brutality, economic disparities, educational deprivation, and unfortunate situations untold,” Bailey says.

She believes that design, engineering, and crafts are therapeutic practices that can heal the community from this socially engineered trauma. She aims to inspire African Americans to surpass the culture of trauma and to encourage folks “to be in touch with their natural talents, in order to support their needs” with the option “to raise the frequency of life through the aesthetic of funk.”

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.