Inside Out

Inside Out

More than once since meeting him in 2015, curator Jennifer Zwilling had seen ceramic artist Ibrahim Said throw a sizable vessel in public in less than 20 minutes, leaving other accomplished ceramicists slack-jawed.

The 48-year-old Said had also demonstrated to Zwilling—at prestigious showings in select East Coast cities, during workshops and symposiums, and at the wheel—that he possessed the technical skill, “feel for the clay,” as Zwilling defines it, and wisdom to routinely realize his generative, seemingly borderless imaginings.

But the ways in which Said was beginning to define his next project, set to premier in April 2022 at The Clay Studio’s newly built, state-of-the-art building in Philadelphia? If the scheme were hatched by almost anyone else, it could’ve been dismissed as brash and ill-fated.

After all, it would ultimately involve engineering and then somehow displaying three sheets of kiln-blasted clay that were each nearly seven feet tall, two feet wide, a half inch thick, meticulously engraved, and brilliantly glazed. A feat that would require an almost superhuman understanding of the material’s molecular makeup, not to mention a saint’s patience. Which is why Zwilling, who serves as curator and director of artistic programs at The Clay Studio, decided it just might materialize. And if it didn’t, something enthralling would result regardless.

With financial support from the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, Said and two other artists (Kukuli Velarde and Molly Hatch) were commissioned to create work for The Clay Studio’s space-christening exhibit, Making Place Matter. Said’s contribution, titled On the Bank of the Nile, finally came to fruition after three failed, time-consuming, heartbreaking attempts. And it is, as Zwilling anticipated, even more stunning than the original concept.

“One of the things about us being able to give him funding is that it allowed him the space to experiment. He’s brave enough and skilled enough to take risks,” she says. “After trying again and again, and [the work] breaking every time, he actually pushed even further. You only do that if you have incredible knowledge and deep understanding. You need that much-talked-about ten thousand hours. And he passed that a long time ago.”

It’s the culture I lived. It’s a feeling that comes from daily rituals. . . . It shaped me and it shaped my world.

Ibrahim Said

Bustling Beginnings

At the age of 6, Said began visiting his father’s humming ceramics studio in Fustat, a neighborhood in Cairo that was the first Muslim capital of Egypt before being absorbed by the larger city; it remains renowned for its titanic, high-octane commercial pottery industry. “I was always playing around in there. It would make my mother crazy,” Said says, animated by the memory. “Seeing all the pottery and forms that people made was very important for my development. It was my college. It was my art school.”

The family business demanded speed and concision. By the time he was a teenager, Said says he was throwing so many pots in so little time he came to briefly loathe the wheel’s potential for mass production, preferring to hand-build and hand-carve the clay whenever possible. His father supported these impulses in his son—without necessarily intending to—by occasionally letting the “production cycle” lapse and lingering over a detail or a distinctive flourish in his own work. It was a practice that made his studio a hangout for groundbreaking makers. “My father had a lot of artist friends,” Said says. “Over the years, many people would come to him to help do something on the wheel. So I saw what artists were thinking and how their ideas were growing.”

At the same time, the maturing Said consistently found himself enchanted by his surroundings: The traditional Egyptian architecture, exemplified by the oldest mosque in Africa, which he walked past most every day of his adolescence. The geometric patterns and arabesques typical of the Islamic art that crowded his favorite museums and everyday haunts. The smell of wood fire in the air. The dust from marble and granite quarries.

“Egyptians are really rich in culture,” says Said, who emphasizes that what he’s referring to transcends any particular type of carving or design. “It’s more than that. It’s the culture I lived. It’s a feeling that comes from daily rituals. . . . It shaped me and it shaped my world.”

With the full-voiced encouragement and material support of his proud father, Said left Egypt for the first time in 2002 to attend a craft fair in Belgium. The experience convinced him to further explore his passions, including specific types of Egyptian pottery, such as the vase forms from the Naqada III period in Egypt (3200 to 3000 BCE), as well as broader creative concepts involving storytelling, tradition, and remembrance.

A decade later—after participating in competitions and showcases in Qatar, Spain, Oman, Kuwait, and Shanghai—Said emigrated to Greensboro, North Carolina. “It’s a really incredible town,” says Said’s wife, the painter and art professor Mariam Stephan. “It’s big enough and small enough. It’s a really rich community, where artists can stay and grow.”

Ceramist Ibrahim Said.

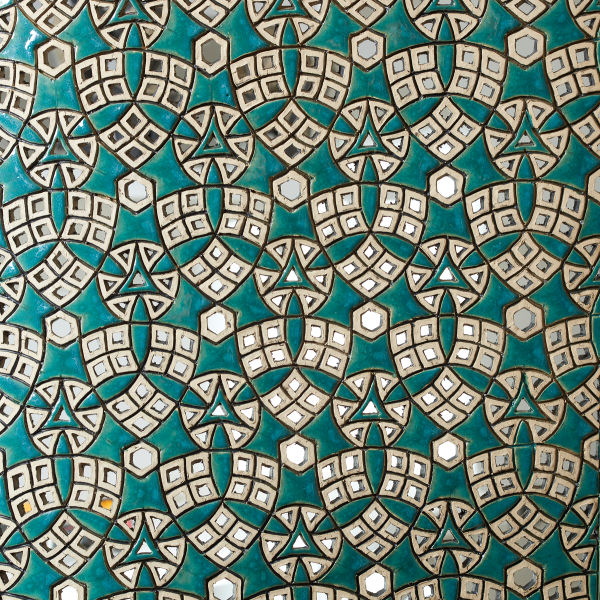

On the Bank of the Nile's geometric shapes, colored Nile green, reflect patterned light.

Seen and Unseen

Before leaving Fustat, which he now visits once or twice a year, Said found himself pushing boundaries out of necessity. “In Egypt, artwork is often copied. You’d find your piece in a show before you’ve even made it,” he says. “I would make myself do work that would be so hard to copy, so daring, that I hoped those who might take my ideas would think it easier to make something of their own.”

It’s clear that Said’s kind of risk-taking is actually rooted in the technical confidence he developed as a commercial potter. Elizabeth Essner, Windgate Foundation Associate Curator of Craft at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and co-curator of Making Place Matter, says it’s this sort of real-world, market-level experience—where invention is born of an almost existential necessity to produce work—that makes Said’s tool box so formidable. “Ceramics is the understanding that the hand is an extension of the mind,” she says. “You understand it and know it as an embodied experience. And while Said’s background might not fit into some academic ideas of what ‘training’ looks like, he’s been training his entire life.

“His innate understanding of his material allows him to have certain freedom. He knows how to push to that very edge of his potential.”

For Said, the medium demands commitment and trust: “There’s a relationship when you work with clay that you can’t ignore. It is the only material that will listen to you—that will do what you ask it to do. You are easy with it. You are hard on it. And you will usually fail. Once. Twice. Three times. But if you’re very patient, I believe you can do anything with it you can imagine in your head. That’s why I try to have conversations with clay, not about clay.”

When Essner and Zwilling describe Said’s distinctive approach, they alternately reference the size of his creations and his delicate, detailed carvings. Both of these characteristics are present in Said’s most recent vessels, including Hourglass, Gold Rings, and Karnak, which will be exhibited beginning in May at the Yossi Milo Gallery in New York City.

Pieces in Said’s new stoneware Karnak series combine papyrus flower forms seen atop ancient Egyptian architectural columns. The pieces range from 26.5 to 64.5 inches tall.

Front and side views of Hourglass, 2023, an earthenware sculpture inspired by Egyptian water filters, exploring the concept of inner and outer beauty, 55.5 x 22 x 22 in.

“He is going against the nature or rules or laws that the viewer believes define what’s possible,” Stephan says of the upcoming show. “In this case, finding the lightness and balance in the positive and negative spaces is what pushes him to be more inventive.”

Upon examination, the pieces in the series appear somehow inverted. This is deliberate, a riff on a design conceit that solidified Said’s place on the international map not long after his arrival in the United States: a preoccupation with the relationship between the inside and the outside.

His carvings on a variety of vases continue to be directly inspired by artifacts of water jugs made between 900 and 1200 CE in Fustat. These early jugs had filters inside to strain out river sediment. Cut into geometric, floral, and animal designs, the strainers weren’t visible until a person actually took a drink. By making the engravings visible on the outside of his jugs and other ceramic objects, Said reveals what was previously unseen. This is a career-long throughline designed to spark dialogue about public and private, inner and outer, perception and reality. “We might hide things from each other, but you’re always vulnerable,” Said says. “Every person has inner beauty. God doesn’t care how you look on the outside. God cares about your heart.”

Stephan says her husband is also grappling with whether it’s possible to hide something and reveal it at the same time. “This has been an intellectual and formal struggle for him over the past decade,” she says before pivoting back to a discussion of Said’s newest innovations. “He wanted to carve the inside components, but open up the middle. That’s what sort of brought those cutaway sections.”

Even On the Bank of the Nile involves a visual nod to the inside out. The first prototypes were modeled after the mashrabiya, a type of wooden lattice screen associated with Islamic architecture, often covering windows on the upper floors of a building. Carved into culturally recognizable geometric patterns, its basic purpose is to create privacy and discreteness between private and public spaces.

Thin and light in their native form, when made of Said’s clay the mashrabiya needed a unique support. So he taught himself marquetry and built a decorative wooden base for the three ceramic sheets, which, after being bolted in, looked like undulating sails. The resulting title all but wrote itself, thanks to the artist’s feelings for the great river.

“The Nile is one of my most beautiful memories,” Said says. “When I was a child, I would go to the bank and sit and watch the sky and water and be in a new world. Cairo was busy with people. Sitting by the Nile was different. I could think about my career, think about life, think about the beautiful stuff I wanted to create. It felt like being in heaven.”