An Interview with Artist Rogan Gregory

An Interview with Artist Rogan Gregory

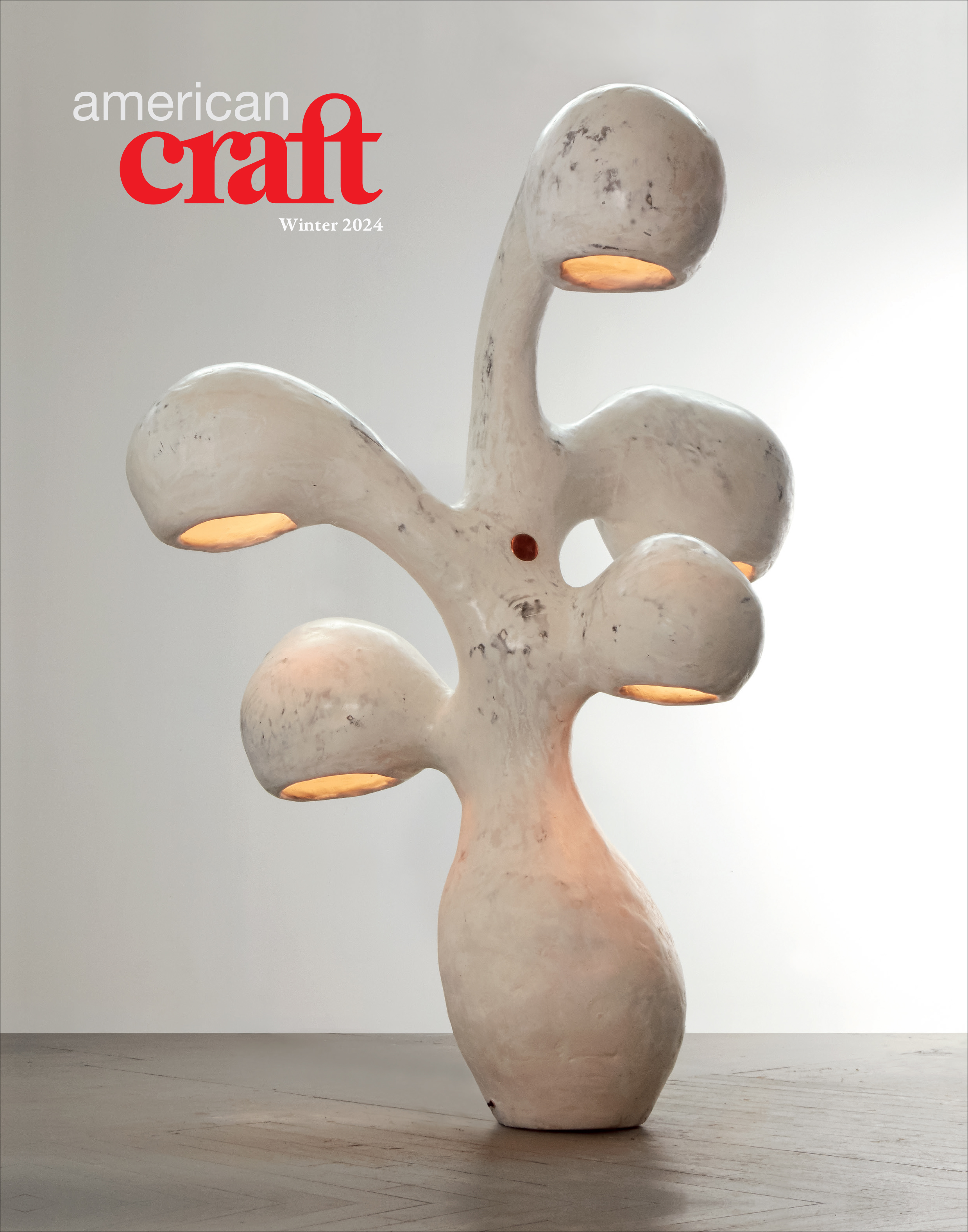

Sinuous and sensual, the honed gypsum floor lamp that graces the cover of the Winter 2024 issue of American Craft was coaxed to life by Rogan Gregory in his sun-washed primary studio in Santa Monica, California. Like much of Gregory’s work, this untitled, illuminated sculpture from his Fertility Form series has an organic presence that animates the interior landscape while bridging the gap between art object and functional furniture.

While Gregory’s gallery/showroom, R & Company, displays a curated selection of the artist’s finished work, his studio is like a mash-up of sculptor’s atelier, archaeologist’s lab, and cabinet of curiosities. The assemblage of chairs, tables, lamps, sculptures, objects, and works-in-progress illuminates both the free-range imagination of their maker and the power of his pieces to elicit anthropomorphic projections.

Some objects gesture toward animals, others at primordial plants, and several evoke hybrids of both flora and fauna. A chandelier with multiple arms blooms and hovers from the ceiling like a many-headed hydra. The textured seat of a splay-legged stool is gently rounded in the manner of a tortoise’s back. And a flock of crook-necked bronze Dune lights peer inquisitively toward a monolithic Venus of Willendorf. Some forms conjure desert-bleached bones; others, excavated artifacts or floating tendrils of kelp. And many pieces evoke humor—such as floor lamps that appear poised to break out in a Merce Cunningham solo. By marrying his imagination and reverence for nature with his fabrication prowess, Gregory creates pieces akin to the love children of Dr. Seuss and Isamu Noguchi.

I recently had the pleasure of chatting in person with Gregory about his work, his philosophy, and his belief in the power of curves to connect us to the natural world.

You’ve said that you hope for your work to evoke joy and emotion, which is not the response elicited by most mass-produced or custom furnishings. Although your works vary in scale, materials, and function, they all eschew right angles, by design. Are they intended as biomorphic correctives to the tyranny of our rectilinear built environment—like a connective tissue to the emotive shapes found in nature?

RG: Yes, and yes. The most efficient way to lay out a city or to build a structure is a square box or on a grid. However, it’s not the most livable—and there’s a whole science around this. Even going for a walk, there’s a difference between moving in a straight line and meandering along a curving path, which is really good for the brain.

For me to carry on doing what I do, I need to have some raison d’être. And my life thesis is that we were not meant to be living in square buildings, sitting in rooms surrounded by flat surfaces. We didn’t evolve that way and I don’t believe it's good for us. It’s not like I was one day thinking, You know what the world needs? More round stuff! But there’s something about being in the presence of these shapes that is therapeutic and beneficial—and so nothing in my work is symmetrical and there are no straight lines.

I’m not particularly optimistic about what we’re doing to the planet. But my contribution is an aesthetic one, and I can hope that these anti-synthetic forms—which are not made on a quadruple-axis milling machine but by human hands—might have some kind of impact.

The lamp on our Winter cover is from your Fertility Forms series, in which you loosely interpret the cycle of life—intercourse, implantation, cell division. You’ve also spoken of the primal importance of light. How do these ideas mesh?

RG: The thing I worship most is life on this planet. Because light is the fuel for everything living, my light sculptures always have spheres and spherical bulbs—because they look like eggs, the sun, the planets, all that. The idea is that many of the lamps are either ovo-repositories or ovo-depositors, and evocative of both the life cycle and the light that is essential for life on Earth.

That particular lamp is made of gypsum. But you’re equally agile manipulating brass, stone, alabaster, terrazzo, plaster, wood, clay, and glass. Yet you’ve had no formal education in either fashion or carving, casting, sculpting, and the like, correct?

RG: That’s right. Just one art class in high school with a great teacher where I made an insane amount of ceramics! I’m so fortunate that my dad, a sociology professor who made sculptures at night and [on] weekends, out of anything and everything—including a pile of old silverware—handed me a chain saw at age 9, when we built a 35-foot hemlock totem pole up in Canada. He was my ultimate art teacher and he still makes work every day. Because I never learned the “right way” to do certain things, I’m not afraid to approach a material, pick up a new tool, and devise a novel way to work with them.

Gregory’s Boniface, 2022, is an illuminated sculpture covered in sheepskin that stands at about 8 feet tall. Photo by Alexa Hoyer, courtesy of R & Company.

Inside Gregory’s studio. Photo by Joe Kramm, courtesy of R & Company.

Inside Gregory’s studio. Photo by Joe Kramm, courtesy of R & Company.

Rogan Gregory’s gypsum lamps including (left to right) Loe Depositor, 2022, 66 x 31 in.; Ovorepository, 2022, 91 x 24 in.; and Tiny Dancer (Ballerina), 2022, 68 x 18 x 22 in. Photo by Joe Kramm, courtesy of R & Company.

Back in the aughts, you won a Vogue/CFDA Fashion Fund Award for your eponymous line of denim and spearheaded two other celebrated clothing lines, one with Bono. How did you pivot from fashion to art?

RG: The definition of success in the clothing business is to make 10,000 of something. But for me, when something did well, it was my cue to try something else instead. When I realized it’s not what I wanted my life to be, I started making objects on weekends, because it made me happy. But I never thought it would be possible to make a living this way because I could always hear my dad’s voice saying, You can’t make a living as an artist. It’s not a viable occupation! Honestly, not one person in my life thought it was a good idea, except for Evan Snyderman at R & Company. And it worked instantaneously: the first show, in 2015, sold out.

Furniture and illuminated sculptures by Rogan Gregory inside his Santa Monica, California, studio. Photo by Joe Kramm, courtesy of R & Company.

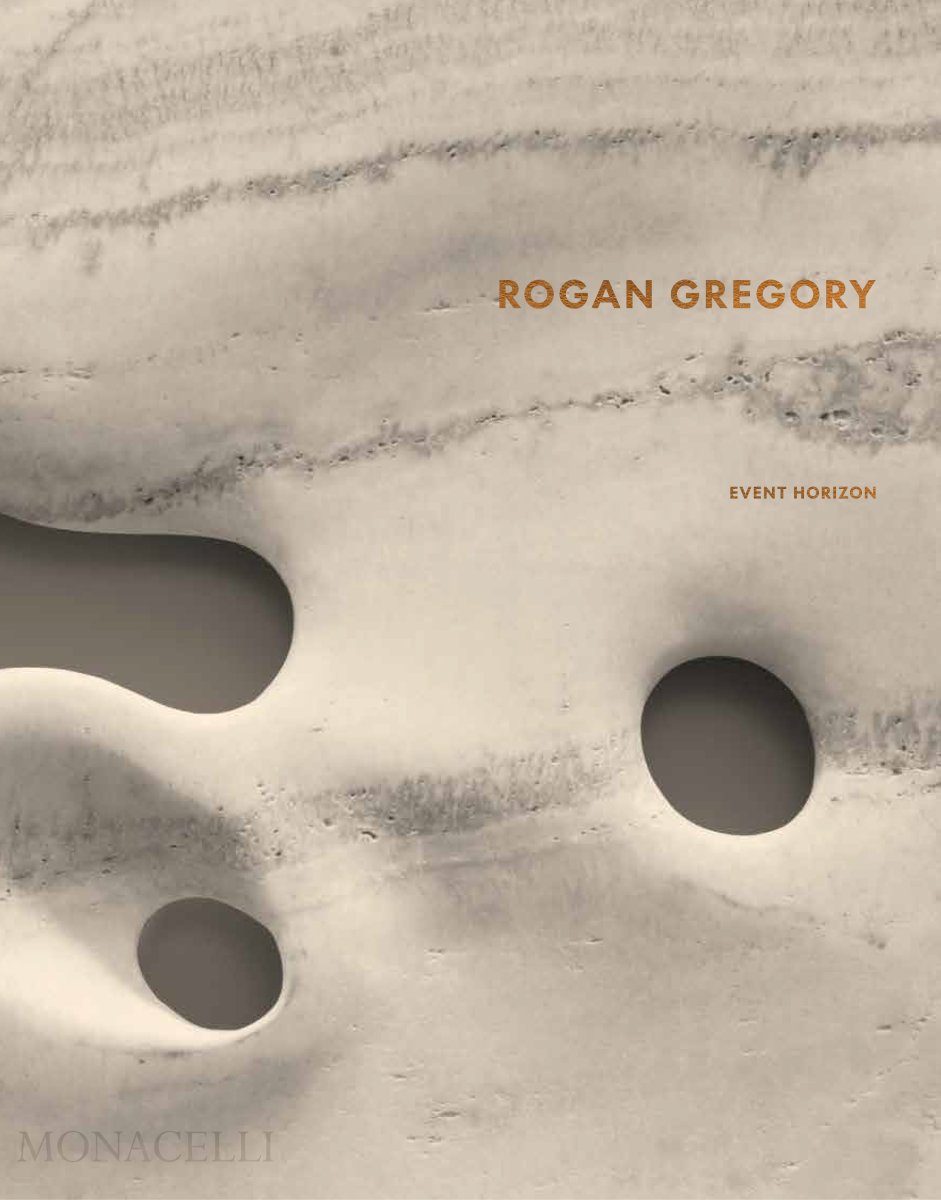

Perhaps your father [Stanford Gregory] makes up for it with his contribution to your recent monograph, Event Horizon. I love how his essay about your embrace of asymmetry embarks: “Order and conformity have never been Rogan Gregory’s modus operandi.” Your sister Tremaine, a biological anthropologist, also wrote about your work through the lens of her field. Clearly, your family is an integral part of your artistic development.

RG: Absolutely. I grew up in Ohio in a scientific milieu where nature was hugely important. We spent summers in the Canadian shield, where the receding glaciers scraped everything off, leaving these lakes, cliffs, and boulders. It’s harsh and minimalist, like a Japanese landscape. I grew up studying these forms, as well as looking at plants and animals and trying to understand why they do what they do. Why kelp floats a certain way, or how a coral reef reproduces. And that’s the impetus for a lot of my work.

Event Horizon (Monacelli) was published alongside a 2023 exhibition of Rogan Gregory’s work at Jeff Lincoln Art & Design in Southampton, New York.

A chair by Rogan Gregory. Photo by Joe Kramm, courtesy of R & Company.

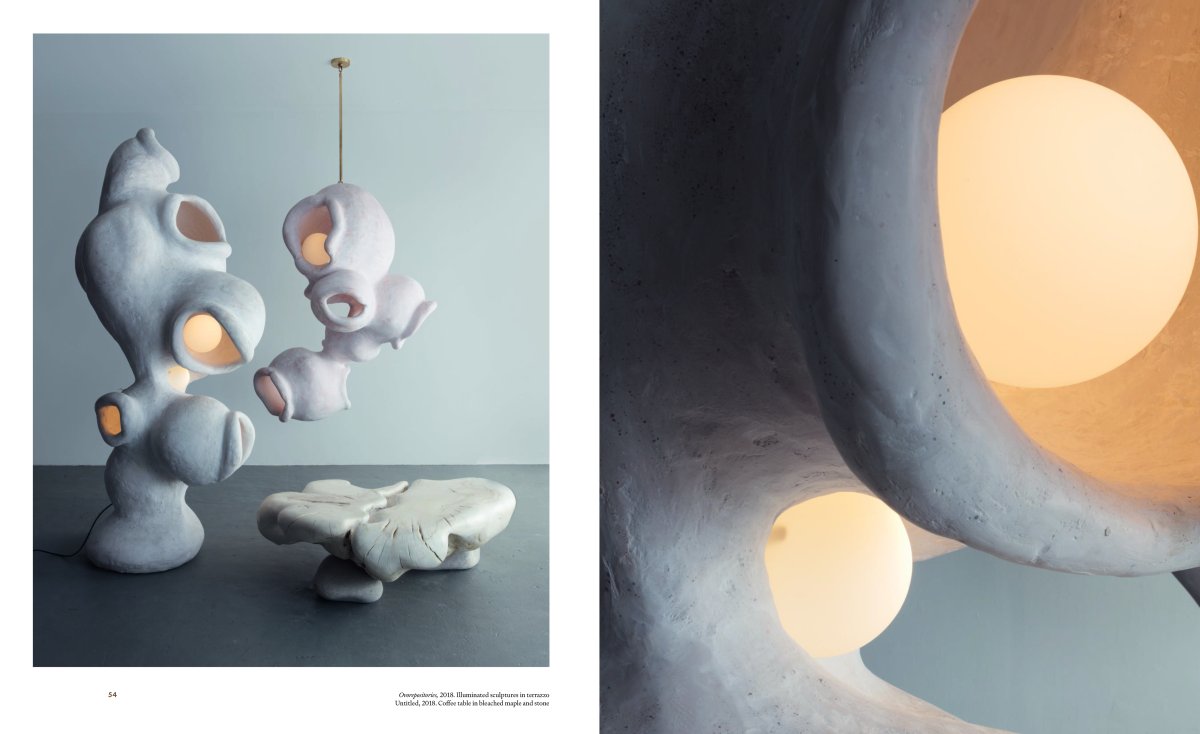

Ovorepositories, 2018. Illuminated sculptures in terrazzo. Untitled, 2018. Coffee table in bleached maple and stone.

Your work has a salubrious effect on those who live with it but, realistically, is inaccessible for a large swath of the population. How does great design trickle down to an audience that might be equally appreciative?

RG: It’s a great question and I do think about it. And while it’s not something I could do with my work, it’s not to say I wouldn’t be open to a collaboration with, say, someone like Ikea. In fact, I should do something like that, because it really would be more democratic.

Inside Gregory’s studio. Photo by Joe Kramm, courtesy of R & Company.