A Legacy Unceasing

A Legacy Unceasing

Don’t call Hank Willis Thomas a political artist.

Although some media sources use the term for his perceptive, quietly confrontational art, Thomas says his work operates from a broader place. “I would describe my art in the context of my humanity, because it is hard for me to separate the work that I do as an artist from anything else I do in my life,” Thomas says. “I often don’t introduce myself as an artist. I say I am a person.”

For nearly 20 years, Thomas has used his platform as an artist to examine how images manipulate our understanding of identity and history, particularly as they relate to black people and black life. He is an observer and explorer, soaking in the stories of the people around him, deconstructing their narratives to find hidden meanings and universal truths.

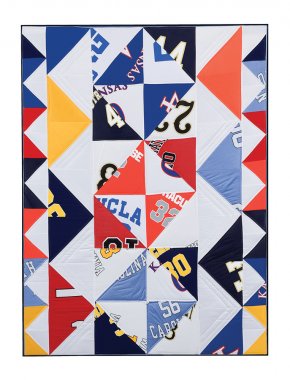

Thomas, born in 1976, earned a BA in photography and Africana studies at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts in 1998, then an MFA in photography and an MA in visual criticism from California College of the Arts in 2004. Those initial areas of interest grew into his current artistic practice. He works in various mediums – photography, film and video, installation, sculpture – and is not tied to a particular technique or approach, instead choosing whatever fits the project. In South Bend (2012), for example, he used cut-up, realigned basketball jerseys to create a quilt more than 6 feet tall. In his Blind Memory series at Savannah College of Art and Design, Thomas examined the region’s history of slavery, filling glass cases with four agricultural products – cotton, indigo, rice, and tobacco – fueled by the antebellum slave economy.

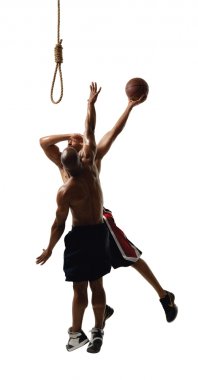

One of Thomas’ best known pieces, 2014’s Raise Up, is a bronze sculpture of black men’s heads and arms emerging from a white base. The sculpture is a three-dimensional interpretation of a famous apartheid-era image by pioneering South African photojournalist Ernest Cole, showing naked miners with arms raised during a medical exam.

The image evokes the conditions and circumstances of contemporary black life: It’s easy to see the men of Raise Up as young black men in the United States with arms raised during a police search. The result is searing, confrontational – and hauntingly familiar. Here, Thomas suggests, little has changed.

Many of Thomas’ sculptures are in conversation with photographs, his own or others’. “Photography gave me justification for something I was already always doing,” he says, “which was looking for the truth.”

Thomas credits his mother – a photographer, collector, and educator – for his interest both in art and in his subject matter. In her capacity as a historian, she developed a keen focus on the exploration and preservation of marginalized and ignored populations, especially people of African descent. “I think I developed a great appreciation for alternative histories and how what’s going on outside of the frame of a camera shapes our notion of the truth just as much as something that’s inside the frame,” Thomas observes.

At first, Thomas was a reluctant student – but his mother would not be easily deterred. “She was more forcing me to do it,” he remembers, “and by the time I realized I was being played, so to speak, I was already following in her footsteps.”

Thomas’ father held many jobs – soldier, chemist, physicist, film producer, jazz musician – and Thomas says that continual reinvention inspired him. “I think his constant search for new beginnings and new opportunities and new ways to explore the world was something that I witnessed pretty closely,” Thomas says. “I think I warmed up in a similar style in my work, which is eclectic, and it’s reflective of both of my parents in their approaches to the world – to life.”

For one such exploration, 2017’s All Power to All People, Thomas built an 8-foot-tall, 800-pound aluminum and stainless steel Afro pick, with a clenched fist topping the handle, placed across from Philadelphia’s City Hall on Thomas Paine Plaza. In his artist statement, he notes, “As an accessory of a hairstyle, [the Afro pick] represented counterculture and civil rights during one of the most important eras of American history. It exists today as many things to different people; it is worn as adornment, a political emblem, and signature of collective identity. The Afro pick continues to develop itself as a testament to innovation. This piece serves to highlight ideas related to community, strength, perseverance, comradeship, and resistance to oppression.”

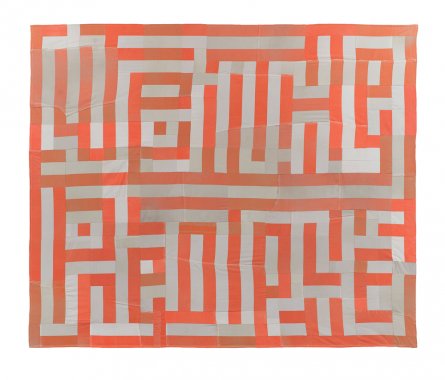

Now Thomas aims to take these ideas, and those of fellow artists, to the political world. In 2016, Thomas co-founded For Freedoms, the first artist-led super PAC. If all art is political, he wonders, why is art so far removed from the political process? Super PACs are “political advertising agencies,” Thomas says, and For Freedoms aims to advertise artists’ ideas to the decision-makers in public office. “I thought that by creating For Freedoms,” Thomas says, “we would be able to hopefully propose the idea of art having a necessary role in civil society, but also encouraging the ideas throughout the world, and not just in museums and galleries.”

This is a new kind of project for Thomas, but it is also the continuation of a lifetime of exploration. He was raised not to be afraid of breaking artistic barriers, to view challenge as opportunity. It is a lesson he has never forgotten.