Life on Earth

Life on Earth

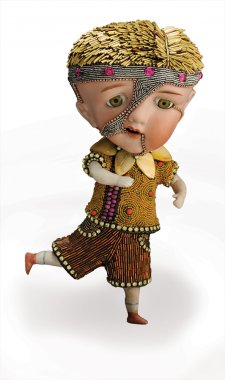

Betsy Youngquist’s creatures are “all harmless and charming, but they can be off-putting because they’re not quite right,” says the 54-year-old artist, speaking from the spacious attic studio in her Rockford, Illinois, home. She uses beads, quartz crystals, and antique doll parts – all lovely by themselves – but combines them to create disquieting hybrid creatures: a bird standing on pale, skinny human legs, a dragonfly nymph that seems true to its species except for its human eyes, teeth, and lips.

The roots of Youngquist’s creativity trace back to her childhood. Her parents enrolled her and her two younger brothers in art, music, drama, and dance classes, “to see where we landed, interest-wise.” During one summer-long Airstream family trip to Alaska, she became fascinated with Northwest Coast artifacts and Native American beadwork. In high school, art was her favorite subject, “but there was no pathway to becoming an artist,” she says. She turned to another love, biology, studying at Chicago’s North Park University. (She was already certified as a scuba diver and joined the Cousteau Society.) Just a few years later, she returned to her first passion, earning a master’s in arts education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Returning to Rockford, her hometown, Youngquist began incorporating bits of foil paper and beads into her watercolors. She met R. Scott Long, her partner for more than 20 years, through a mutual friend when they were both “fledgling Rockford artists.” The two began collaborating on three-dimensional bead-covered animals. He made the figures out of epoxy clay, wire, and urethane foam; she added doll parts and beading.

One day, a doll head broke off. Reattaching it resulted in an off-kilter redo and a eureka moment. “It was the right evolution for the work,” Youngquist says. “I’m a surrealist, which means creating something that isn’t quite in sync with our real, physical world.”

That element of strangeness is eye-catching, but it also reflects a deeper layer of meaning. As Youngquist sees it, animal and human forms are intermingled because life on Earth is intertwined and interdependent. “It’s a way for me to show empathy and stewardship with all life on the planet. If we have the power to destroy, we have the power to be stewards,” she says.

Her art is also a reminder that mystery and magic don’t have to disappear when we grow up. UFOs figure prominently in her work, and dolphins and their apparent ability to communicate over thousands of miles are a source of fascination for her. (“I want to bead a dolphin – I just need to talk Scott into carving me one,” she says.) They’re invitations to explore unknown realms and express imaginative possibilities.

Youngquist’s works can be as small as 1-inch pendants or as large as installations that measure 6 by 7 feet. She likens the process of covering forms with beads to a dance, partly planned and partly intuitive. She attaches the materials with glue, and for most pieces she also adds a layer of black tile grout over the surface, allows it to set, then rinses and scrubs it off the beads. The grout provides additional adherence, but also tames the colors and makes the pieces seem older, as if they were discovered after centuries underground. “There’s something mysterious and primal about a dirt-covered object,” she observes.

If a piece has eyes, though, Youngquist always begins with them, incorporating prosthetics or glass pieces from antique dolls. “I’ve been eye-centric in my art since high school,” she says. “In meeting a creature through the eyes, I begin to understand what each character wants to become.” Still, the process of meeting and making each one must follow its own, often unpredictable, path. Among her best-known pieces is Metamorphosis, a nearly 4-foot-tall, bead-covered human figure modeled by Youngquist and carved by Long. The 2011 work was a response to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico the year before. Initially, the artist thought she would create a black-bead-covered pelican, as if smothered in oil, but she changed her mind. “I realized it needed to be human, because whatever we’re doing to the Earth, we’re doing to ourselves,” she says. With a large beaded butterfly on her back, the figure came to represent “recovery, restoration, and healing,” Youngquist says. “It’s about our inner connection and the world’s beauty. We’re all cells in the same body.”