Look Closer

Look Closer

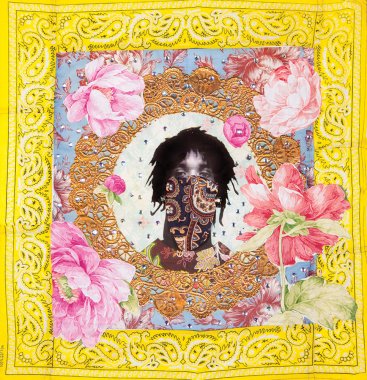

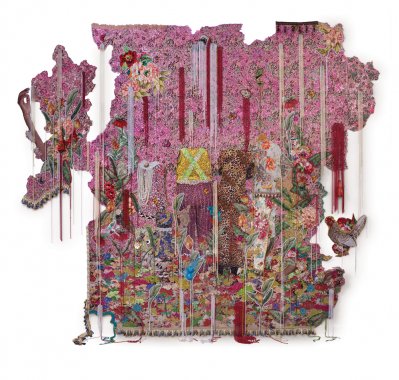

It takes your breath away, that first sight of the color, drama, and shimmer of Ebony G. Patterson’s art.

Walk into a gallery and there it is: a tapestry the size of a movie screen, a lush polychromatic dream of pattern, texture, and imagery, set against a bright pink and white polka-dot backdrop. Densely appliquéd with fabric, glitter, and trinkets, it’s a montage of dolls and unicorns, candy and cupcakes, butterflies and bows – the sweet, simple joys of childhood. At the center is a photographic portrait of two young black girls – best friends, perhaps? – carefree and beaming, haloed in gold Mardi Gras beads like saints in a medieval painting. Balloons float above and around the girls, though several rest forlornly on the gallery floor amid a scattering of trophies, the kind kids accumulate at sports and school. There was a party here, but it’s over.

As your eyes adjust and you home in, a gut punch: The portrait is riddled with holes, bleeding rivulets of red beads. This is a memorial.

…They Were Beautiful Like the Moon … They Were Just Babies … They Were Just Girls. … (… When They Grow Up) is the title of this piece, one of a series by Patterson on the abuse and killing of young people of color. Inspired by a spate of child murders in her native Jamaica (and the suggestion by some that the victims somehow invited their fate), the theme encompasses the systemic prejudices surrounding other violent deaths in the news. A portrait called … They Were Just Boys … shows a pair of young black adolescent males playing with a toy gun – just as 12-year-old Tamir Rice was doing when he was shot and killed by Cleveland police in 2014. “What happens,” she asks, “when a kid is not allowed to be seen on innocent terms?” Why, she asks, are they deprived of the same interests as their white counterparts?

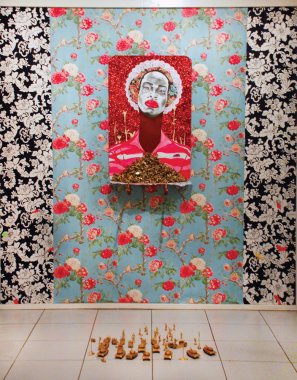

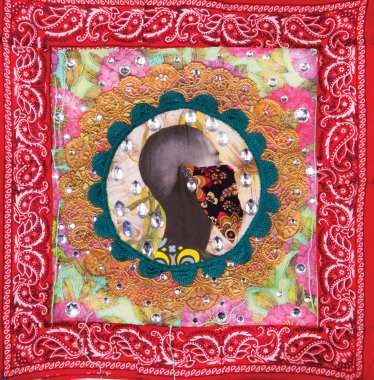

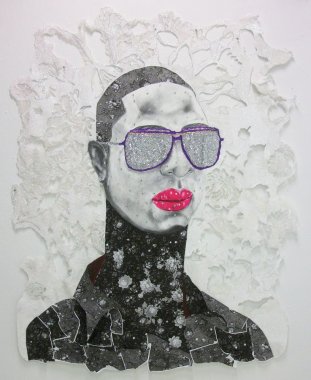

Visibility and invisibility are paramount interests for Patterson, who divides her time between Kingston, Jamaica, and Lexington, Kentucky. Through her work, she examines how people of color and the underclass are seen – and not seen – especially in predominantly white spaces. Her creations explore the ways working-class people often indulge in fashion and material culture as a statement of identity, “to project and reimagine self, in order to assert one’s significance, value, visibility, and dignity.” Lately she has investigated how that practice can be used to commemorate the deceased, especially those who remain largely anonymous in the public realm. In her ongoing Dead Treez series, we stumble on bodies hidden in lush foliage, crime scenes made into strangely beautiful testimonials by the tender application of vibrant decorative elements. Through her use of various materials and disciplines – painting, collage, needlework, assemblage, installation, performance – she creates dazzling declarations of presence that compel us to look and acknowledge.

And she wants us to go a step further, contemplate our own connection to these images.

“They get caught up in its color, and they’ll use words like ‘Oh, it’s so pretty,’ ” Patterson says of viewers’ visceral reactions to her admittedly seductive aesthetic. She’s intrigued when people post selfies with her pieces, grinning in front of some disturbing detail.

Her own feelings about photography and social media are complicated. On one hand, a photo is documentation; on the other, she says, the act of taking someone’s picture is a kind of violation, the “soft murder” Susan Sontag describes in her 1977 collection of essays, On Photography. Social media, likewise, levels the playing field of visibility, carves out space for ordinary people to be seen. Yet when gruesome crime scene photos circulate on the internet, “the act of ‘click, like, and share’ puts those bodies back up for consumption, fetishization, and objectification all over again,” she observes. We maybe can’t help but look, Patterson allows, but what do we do next? If we reintroduce that intrusive shot, are we complicit in that act of violence?

For those reasons, Patterson doesn’t use images of actual victims in her projects. To make a tapestry, she’ll hire models, work with a tailor to design custom outfits for them, and set up a photo shoot. She edits the resulting images in Photoshop, then sends them out to be woven on a jacquard loom. At last she sits down to paint, embroider, and glue embellishments on the weavings. She does the handwork in her studio in Kentucky, but the conception and staging of her visions take place on her beloved island.

“Jamaica is always home, and will always be home,” she says. “Everything that I am is because of the place that I grew up in.” Born in Kingston in 1981, Ebony G. (the middle initial stands for “Grace”) was raised in a solid middle-class household by loving parents who supported her desire to become an artist even if they didn’t fully understand it. Both of them came from poor, rural backgrounds, and many of Patterson’s friends and extended family lived in working-class communities.

She remembers the first time she became starkly aware of social bias, in her teens. Jamaican dancehall culture had entered the mainstream, in the form of nighttime street parties where revelers expressed their personal style and bravado within a flamboyant, “bare as you dare” dress code. “The argument coming from the upper echelons of society was that it was lewd, raucous, low-class,” she recalls. Yet at the annual Jamaica Carnival, an official event, approved participants (from that same upper class) were allowed to parade half-naked down public streets cordoned off for the occasion. The disparity, Patterson concluded, was due to the fact that “one set of bodies come from the lower class and the other from the upper class.” Years later, during the 2014 carnival, she would organize an intervention/performance by 50 marchers carrying hand-decorated coffin sculptures, a nod to “bling funerals” where the poor and working class honor their loved ones with lavish burials.

She attended the Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts in Kingston, then earned her MFA in printmaking and drawing from Washington University in St. Louis in 2006, by which time she was exhibiting in earnest. Her early work dealt with intersections of bling culture, the body, and changing notions of gender – for example, what it means for men to use grooming tools and techniques traditionally associated with the feminine, to create a sense of presence for themselves. After the death of her father in 2010, she turned toward memorialization.

With her work critically acclaimed and in demand, Patterson has a busy schedule of exhibitions (“I asked the universe for it, and so it’s giving it to me, I guess”), including solo shows opening this year at the Baltimore Museum of Art, Pérez Art Museum Miami, and the Monique Meloche Gallery in Chicago. When two of her pieces were featured on the second season of Empire, she was glad for the opportunity to create “a moment of visibility” for her subjects through the far-reaching medium of a wildly popular TV series. Her latest work is focused on acts of witnessing – those instances when bystanders or victims’ loved ones are caught in vulnerable moments by the news media – as well as the garden as a symbol of social demarcation, at once utopian and dystopian. As ever, she’ll make us look – and perhaps see.