Lowrider

Lowrider

↑ Fashioned from a 1985 Chevrolet El Camino in 2014, Rose B. Simpson’s Maria celebrates the artistic expression of pottery and lowriders.

Photo: Kate Russell

Every inch of Maria is matte black, except for the lines and curves of the shiny, geometric design that animates its surface. It looks as though these glossy areas were carefully burnished to make them pop against their flat background. The abstract shapes are inspired by the inventive work of potter Maria Martinez and echo Pueblo motifs of a vast and dramatic natural landscape dating back centuries. As for horsepower, you’d have to ask the artist, Rose B. Simpson.

I should clarify that Maria is a car, not a piece of pottery. Fashioned from a 1985 Chevrolet El Camino in 2014, Maria is Simpson’s homage to two art forms she holds dear, both of which have deep connections to the world she calls home.

↑ Simpson drives Maria to the Denver Art Museum flanked by a squad of post-apocalyptic Indigenous warriors wearing accoutrements Simpson made of leather, metal, found objects, and ceramic components. A heartbeat emanated from a 1,000-watt speaker system in the cab of the El Camino.

Photo: Kate Russell

Lowriders are classic American muscle cars that have been retrofitted with hydraulic systems that allow drivers to raise and lower the chassis (supporting frame) at will, and retro-style wire wheels that shimmer as they turn. Their history can be traced to the community of Mexican Americans living in Los Angeles in the mid-1940s who customized their cars to roll along slowly, allowing onlookers to appreciate their designs in full. Lowriders are made to cruise; they are vehicles for artistic expression.

And yet, “Despite the care and craftsmanship that goes into these cars, they have sometimes had negative associations,” writes Katherine Ware about the New Mexico Museum of Art exhibition she curated, “Con Cariño: Artists Inspired by Lowriders,” which featured Simpson’s Maria. (Currently, the lowrider is touring the nation as a part of the exhibition “Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists,” scheduled to open October 7 at the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma.) One-dimensional and sensational depictions of life in the Southwest have led to an association between low-riders and gangs. According to Ben Chappell, the author of Lowrider Space: Aesthetics and Politics of Mexican American Custom Cars, this perceived link is largely unfounded. The investment of time and money that the customization of lowriders requires suggests a life of stability and access to resources. He describes one of those resources in a New York Times interview as what many would recognize as a craft community: one of mechanical know-how and tools. “[A] car should be an expression of the owner,” he says, “and you have to work to build and maintain it. So working on cars and sharing knowledge is a big part of it. People will barter labor and parts. There’s a really extensive social network around lowriding.”

↑ Maria is part of the traveling exhibition “Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists,” shown here in 2019 at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Photo: Courtesy of Minneapolis Institute of Art

Many might assume that the lowrider world is exclusively male, but Simpson proves that isn’t true. In addition to holding an MFA in ceramics from the Rhode Island School of Design, she is an expert in lowrider customization, a form of auto body work deeply rooted in New Mexico’s car culture. After finishing up at RISD, Simpson moved back to the Southwest. “Instead of moving to New York City like many of my peers,” she says, “I came back home and enrolled in the automotive science program at Northern New Mexico College because I have always been inspired by the Española Valley community that I grew up in – the Lowrider Capital of the World.”

The artist grew up on the Santa Clara Pueblo in northern New Mexico, and is a member of a family that includes generations of ceramists. Her mother, Roxanne Swentzell, is a figurative ceramic sculptor who, according to Simpson, built the house they lived in, fixed cars, and never let anyone borrow her chain saw. Her father, Patrick Simpson, is a sculptor who works primarily in wood and metal. Simpson’s maternal grandmother, Rina Swentzell, made contemporary pots on the wheel. Her great-grandmother, Rose Naranjo, and several of her nine children, made traditional pottery by hand. For a period of time, her mother turned off their electricity to see if they could live off the grid. “We were very empowered to figure things out on our own,” Simpson told Pasatiempo magazine. Thus Simpson comes from a culture where men and women get equal time making things, using tools, and solving problems, as well as shaping evolving traditions to meet the moment.

↑ Simpson with her piece River Girls (2019). The mixed-media artist’s practice engages ceramic sculpture, metalwork, fashion, performance, music, installation, and writing.

Photo: Kate Russell

Maria is named after and inspired by the work of potter Maria Martinez (1887 – 1980) who was born and raised in San Ildefonso Pueblo, about 10 miles from where Simpson grew up. By the time Martinez began making pottery, the proliferation of commercially produced wares had drastically reduced the need for handmade ceramics for use in daily life. The work for which Maria Martinez is renowned, then, is not part of a static and unbroken Pueblo tradition; rather, it was a conscious historical revival and a form of artistic innovation. In 1907, Dr. Edgar Lee Hewett, director of the Museum of New Mexico, approached her about creating replicas of ceramics based on recently unearthed shards for a museum display. Already known as a talented potter, Martinez began working on these revival forms along with her new husband, Julian Martinez, a self-taught painter. The pair began experimenting with surface designs and techniques; she made the vessels, and he decorated them.

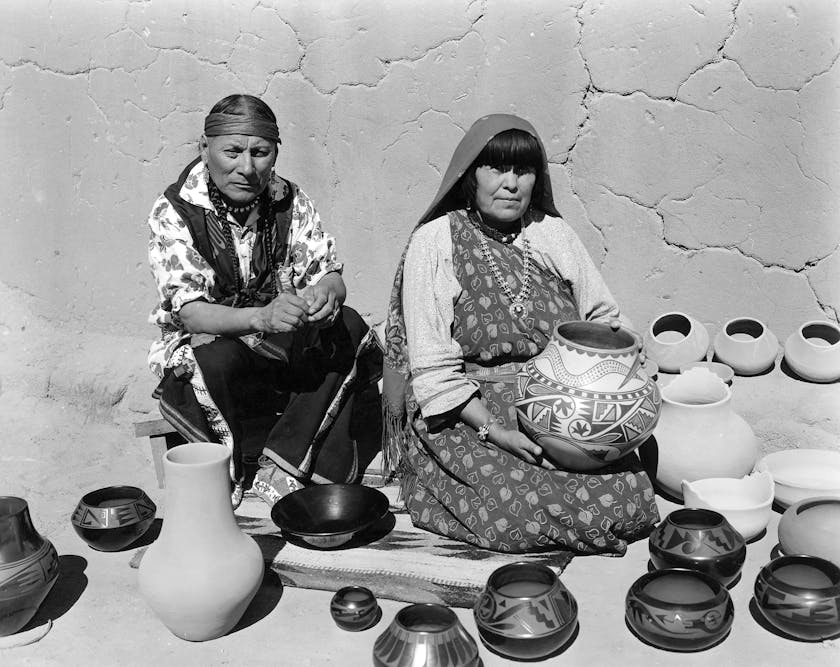

↑ Julian and Maria Martinez in an undated photo displaying finished pottery at the San Ildefonso Pueblo in New Mexico.

Portrait: Wyatt Davis, courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives

↑ Maria Martinez and Julian Martinez, Plate, ca. 1930s, blackware, 1.9 in. x 14.6 in. dia.

Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum

↑ Maria Martinez and Julian Martinez, Bowl, undated, blackware, 6.7 in x 9.5 in. dia.

Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum

↑ Santana Roybal Martinez and Maria Martinez, Feather Bowl, 1948, polished black matte ware, 2 x 14.9 in. dia.

Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum

By 1918, they had produced the first of their first black-on-black pieces, and these vessels, with burnished designs that stand out from a matte background, earned wide acclaim. Martinez became a symbol of Southwestern craft and Pueblo aesthetics, demonstrating pottery-making techniques at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, the 1914 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego, and the 1934 World’s Fair in Chicago. It may not have been obvious to buyers and collectors at the time that she wasn’t merely carrying on an existing ceramic practice, but revitalizing and adapting one to new times. She made her pieces individual expressions of her artistic intent by signing them, something that Pueblo potters had not typically done in the past.

“I knew about Maria Martinez’s work for most of my life, as many people in my community made work similar to hers,” Simpson tells American Craft. “Her black-on-black style was groundbreaking and incredibly influential. The designs that her husband, Julian, painted on her pots are cultural symbols and metaphors for a lifeway and perspective that I am familiar with, sharing the same Pueblo culture and place-based religious belief system.”

For Simpson, cars were as much a part of her local ecosystem as art was. As she told Pasatiempo magazine, “In Española, when I was growing up, I saw lowriders everywhere.” She fixed up her own used Jeep Cherokee before she even entered middle school, so her choice to use a car, of all media, as a tribute to Maria Martinez is meaningful: “I am paying homage to the back-and-forth ties of history and preservation and customization and recycling and inspiration and cultural integrity. Vessels such as the ones that Maria Martinez created are no longer in daily functional use for many Pueblo people, but vehicles are.”

The work for which Maria Martinez is renowned ... is not part of a static and unbroken Pueblo tradition; rather, it was a conscious historical revival and a form of artistic innovation.

Simpson rebuilt and customized Maria during her 2013 residency at the Denver Art Museum, adding a custom-made 410-horsepower, 350-cubic-inch small-block engine – one reason why she describes Maria as a “power object.” It was there that she premiered the piece in front of the museum, driving the car herself, as seven models sporting Mad Max-inspired leather ensembles accompanied her on foot. The car’s sound system played the sound of a human heart beating at full volume. Though a viewer unaware of Maria Martinez’s oeuvre likely wouldn’t think of ceramics while witnessing Simpson’s performance, her choice to frame Martinez’s motifs in the form of a lowrider is perfect. For the artist, the lowrider is also a vessel, metaphorically and literally, for wildly original work emerging from and iterating upon traditions.

This article has been adapted from “Power Object: Rose B. Simpson’s Maria,” from American Craft Inquiry: Volume 2, Issue 1.

What do you think of the lowrider as a craft medium?

We'd love to hear from you. Send your reactions, reflections, questions, and concerns to [email protected].

We need your help to share artists' stories

Become an American Craft Council member and support nonprofit craft publishing. You won't just receive our magazine – you'll help grow the number of lives craft has touched.