Maker Spotlight: Jorge Palacios

Maker Spotlight: Jorge Palacios

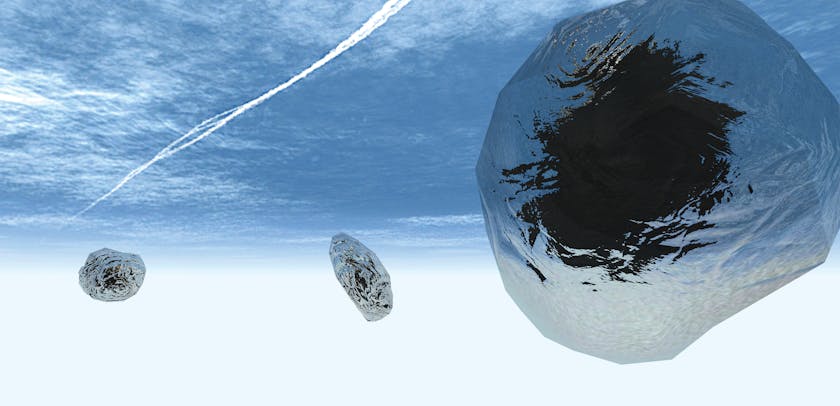

↑ For their installation Ancestors (2019), Jorge Palacios created glass meteorites and a video game with a handmade glass controller. Viewers use the game to explore Indigenous kinship through projected images and poetry.

Photo: Eden Tai, courtesy of Jorge Palacios

Glass is not a medium Jorge Palacios, who identifies as nonbinary, ever thought they’d work with. While growing up in San Antonio, they immersed themselves in the fantasy world of sci-fi and video games. “They were my escape from reality,” says the 23-year-old. Intending to develop skills to explore a career as a storyboard artist for video games, they only discovered glass after entering a dual program in astrophysics at Brown University and art at Rhode Island School of Design. “It’s an unusual and really beautiful medium that commands presence, vulnerability, and intimacy,” Palacios says, which makes it a good fit for their multimedia art that sits at the intersection of physics, ancestry, and legacy.

↑ The Ancestors installation combines user-controlled digital imagery, poetry, and a tactile environment of soil and fiber. Palacios rolled molten glass on land to create the meteorites (right).

Photos: Eden Tai, courtesy of Jorge Palacios

Palacios is a Mexican-American Xicano with Indigenous roots in central Mexico. Their parents immigrated to the United States in the 1980s, and their grandparents didn’t share specifics about the family’s history before passing away, so Palacios makes efforts to fill in this missing family history through research, art, and imagination. “It’s interesting to me what kind of narratives I had to fill in as a child, and to think about the kind of futures I had to imagine.”

Now their multimedia installations employ blown- or cast-glass objects with digital or print mediums, such as video games, photography, or writing, to examine their family history or the history of the land they occupy at any given time. They are intrigued by exploring new worlds while honoring not only their family’s history but also the histories of Indigenous peoples everywhere. “A lot of my work stems from displacement and what taking up space on stolen land might mean.”

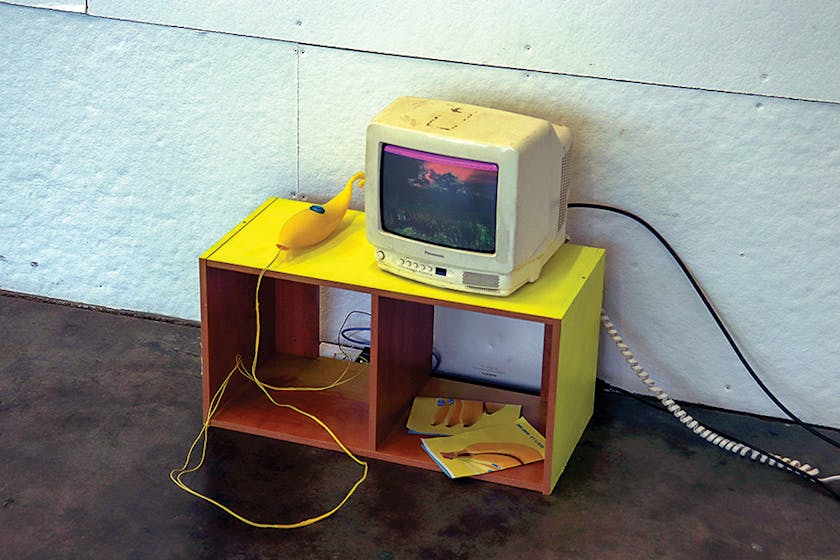

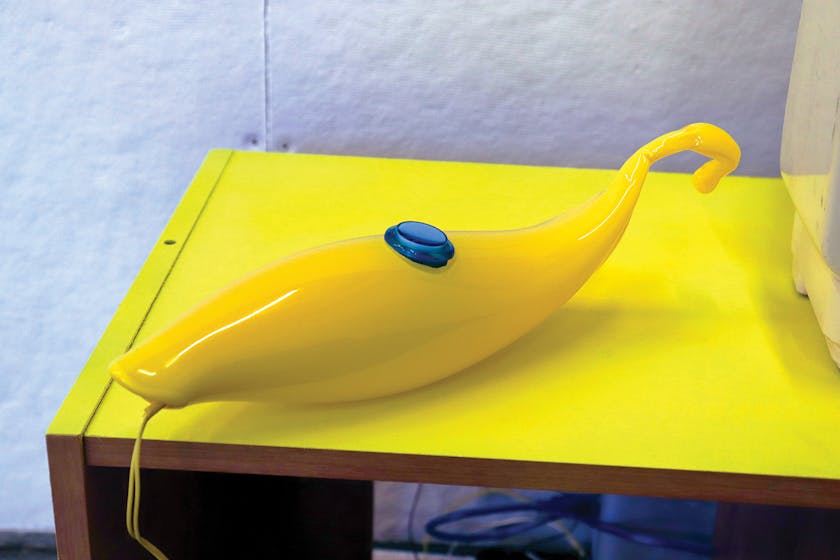

For Convergence (2019), Palacios first created the blown-glass controller in the hot shop, added a color overlay, and – once the glass had cooled – cut and polished holes to accommodate the electronic components. The controller allows users to navigate through 3D objects and 2D images floating in digital space inside the glass orb.

Photos: Courtesy of Jorge Palacios

For the installation Ancestors (2019), Palacios engineered “meteorites” by rolling molten glass directly on the land of the Narragansett and Wampanoag tribes (which today is Rhode Island and Massachusetts). They then silvered the interiors of the meteorites to create a mirror-like effect that reflects “the earthly ancestral information recorded on their surface texture.” To accompany the meteorites, Palacios designed a video game depicting a utopian-like digital universe with poetry exploring the themes of identity and Indigenous kinship for the viewer to explore with a handmade (and hand-wired) glass controller.

In 1954, the US backed a coup d’etat overthrowing the Guatemalan president in support of the United Fruit Company. Palacios, thinking about this and other coups d’etat in Latin America, created Gorilla Warfare (2019). In this video game, the user plays a Guatemalan farmer and uses a magical glass banana to defend against trained US troops.

Photos: Courtesy of Jorge Palacios

Convergence (2019), which took Palacios a week and a half to make, consists of a glass controller and orb that has an image projected onto both its front and back hemispheres. Using the controller, you can navigate through many 3D objects and 2D images floating in digital space within the orb. Palacios describes the work as a means to collapse timelines “to experiment with ways of engaging with the ancestral past and ourselves as ancestors of the future,” as well as an exploration of utopias.

For On the Land (2020), a glass piece with no technology, Palacios used soil casting – as opposed to the more common technique of sand casting, which involves pouring molten glass into imprinted sand – to cast footprints in the earth. “I wanted to make a piece that bridged my feelings of displacement and also of being in Providence, Rhode Island, [and at RISD] for five years,” they say. “The piece revolves around soil and uses the physical substrate that the school was built on to speak about histories and how I was inhabiting the space.”

↑ Palacios poured glass onto their footprints in the soil on the RISD campus to create glass feet for On the Land (2020). The project, a study in displacement, also includes photographs.

Photo: Courtesy of Jorge Palacios

The artist graduated from Brown and RISD last spring. They are now back in San Antonio with family and plan to continue their multi-media art while also exploring careers in physics. “It took some convincing for my family to understand the value of this work, but today they are very proud of me,” Palacios says. “I hope that my art can change people’s perspectives and provide healing.”

What do you think of Jorge's work?

We'd love to hear from you. Send your reactions, reflections, questions, and concerns to [email protected].

We need your help to share artists' stories

Become an American Craft Council member and support nonprofit craft publishing. You won't just receive our magazine – you'll help grow the number of lives craft has touched.