Maquettes at the McNay

Maquettes at the McNay

Stage sets may be the most eloquent co-stars in any performance to never say a word. Yet as actors, choreographers, lighting designers, and others bring a show to life, sets speak volumes: Does the street where Boy meets Girl inspire joyful gestures or fearful whispers? Is their apartment cozy or nightmarishly claustrophobic?

Because sets might not be built and installed until rehearsals are well underway, scene designers create maquettes: usually three-dimensional, dollhouse-size, to-scale renderings of their visions for the cast and crew to refer to. Designers might use wood, paper, wire, metal, string, fabric, plastic, photos, or found objects, incorporating elements of sculpture, collage, and assemblage.

Among the 12,000 rare books, costumes, paintings, and other objects in the Tobin Collection of Theatre Arts at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio are about 250 maquettes. Some were made by designers working strictly for the stage. Others were crafted by artists for whom scene design was an intermission in a fine-art career – among them Pablo Picasso, Erté, Louise Nevelson, Fernand Léger, Jean Cocteau, David Hockney, and Robert Indiana.

A designer might make several maquettes for a show, or just one. “Scene designers must plan for all settings of the story and then consider what is needed in those settings,” explains R. Scott Blackshire, the collection curator.

For a 1977 production of Alban Berg’s opera Lulu, the tale of a young woman’s descent from wealthy mistress to impoverished prostitute, Jocelyn Herbert created a series of maquettes that begins with a luxurious interior and ends with a stark, shabby room. “[They] communicate a visual arc of Lulu’s downfall in life and allow the singer to imagine the emotional changes her character might experience living in these very different environments,” Blackshire says.

By contrast, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s In the Heights (2007) takes place entirely on one street in the Washington Heights neighborhood of New York City. To render it on stage, designer Anna Louizos visited the neighborhood, photographed and sketched the skyline, then created a maquette of a crowded streetscape that lends itself to everything from exuberant dance numbers to intimate duets.

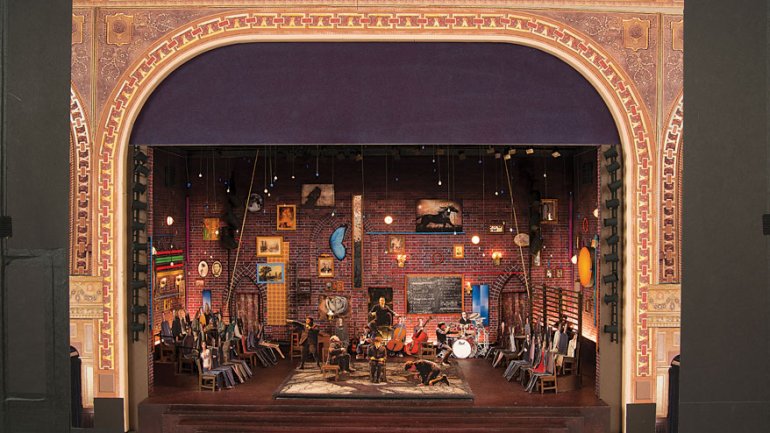

Some maquettes are marvelously specific, such as Christine Jones’s for the musical Spring Awakening (2006), with working lights, intricate arched doorways, and brick walls embellished with tiny paintings, portraits, and a chalkboard covered with legible writing. The final Broadway set may have differed from its mini-me in a few details, but all of its key elements are present.

Visitors to the McNay can see selected maquettes in shows such as this year’s “Picasso to Hockney: Modern Art on Stage,” opening in October. Maquettes are usually displayed on pedestals within plexiglass vitrines so visitors can see them in the round and appreciate all their details. “People do get close,” Blackshire says. “Every now and again, we need to wipe nose prints off the vitrines.”

In the upcoming show, the curator’s personal favorite will be on view: Picasso’s subtly colored cardboard maquette for the ballet Le Tricorne, which is “very different than the portraiture or other cubist work we know from him. As an artist designing for stage, he tapped into his softer side.”

For the future, Blackshire contemplates acquiring work from more women designers, as well as contemporary American designers whose work “captures the growing diversity of America. I would like to identify designers who reflect the spectrum of art lovers we serve – in San Antonio, the region, the state, the nation, and beyond.”