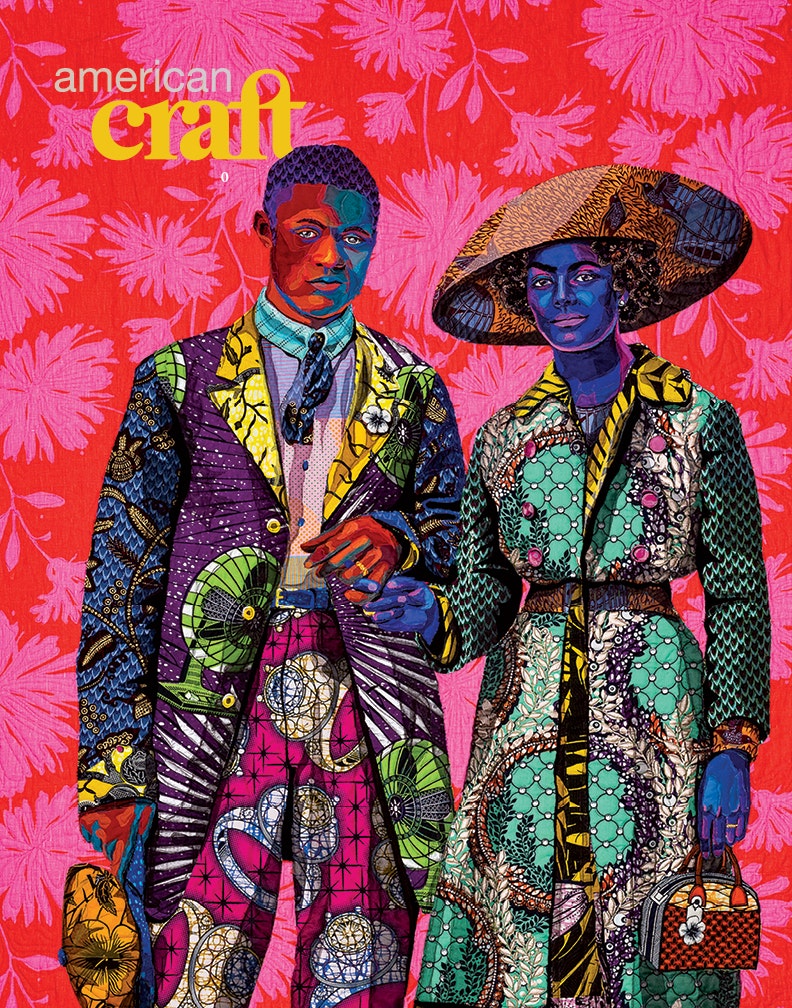

More Than a Plate

More Than a Plate

Black Lung: A Terrarium for Black Breath includes salad leaves and chicken-fried mushrooms. It’s served inside a glass sphere on a ceramic plate that’s a reproduction of the West Philadelphia sidewalk. Photo by Elena Wolfe.

“Plateware has always been important to me, but I could never really afford to buy plates that are specific to the dishes I make,” says Tate, who runs a recurring pop-up dinner series called Honeysuckle in places like New York, Philadelphia, and Martha’s Vineyard and was named Esquire’s Chef of the Year in 2020. “All I could really control from my end were the food and presentation.”

To showcase his multicourse meal, which reflects the Black American experience, Tate met with artist, designer, and ceramist Gregg Moore and quickly realized their relationship would last well beyond the residency. “Meeting Gregg opened up a whole world of possibility for me in the form of what ceramics can be and how it can help create an immersive 360 experience,” says Tate. “Gregg isn’t just some dude who make plates—he’s not Crate and Barrel, you know?”

For his first course, Tate served a dish called Black Lung: A Terrarium for Black Breath, an ode to Black lives lost in conflict in 2020. Bright green salad leaves and chicken-fried mushrooms are served inside a delicate glass sphere on what looks like a slab of asphalt. In reality, it’s a porcelain plate Moore made based on the sidewalk in front of Tate’s mother’s house in West Philadelphia. Tate and Moore together made a plaster cast of the actual sidewalk—with a drainpipe cover, moss, and the name POOKA carved into it—which Moore used as the model for the plate.

Gregg Moore and Omar Tate make a plaster cast of a section of sidewalk in front of Tate’s mother’s home in West Philadelphia. Photo courtesy of Blue Hill at Stone Barns.

“2020 was a difficult year for us all, and the palpability of Black death made it even more treacherous,” Tate explains. “The cast of concrete, a drainpipe cover, moss, and etching of the name POOKA was chosen to examine the tension between black bodies, concrete, and nature in cities and ghettos.”

Another course that Tate conceived, called Notes on a Black Pantry, was served in dishes inspired by colonoware, a type of earthenware pottery made and used by enslaved people during the colonial period. An intact colonoware dish has never been found, says Tate, so Moore purposely created shards of pottery that Tate used to serve his course in fragments at the table. The various pieces of pottery featured confit ham, smoked plantain puree, carrots poached in carrot juice, and what Tate called Cabin Spice, a blend of spices, including clove, nutmeg, allspice, cardamom, and black pepper, that could be used as a condiment.

Colonoware is an unglazed earthenware made and used by enslaved people in colonial times. Omar Tate and Gregg Moore’s design for these ceramic fragments was informed by the fact that no piece of colonoware has ever been found intact. Photo by Elena Wolfe.

“I wanted to represent the spice trade, which was one of the largest perpetuators of the transatlantic slave trade,” says Tate. “The irony is that folks were brought here because of spices and then were not allowed to use those spices. If they did, they would have to use it in secret” in their cabins.

Omar Tate is one of many chefs who’ve collaborated with Gregg Moore this year at Stone Barns Center, which houses Blue Hill at Stone Barns, the pioneering farm-to-table restaurant helmed by chef Dan Barber. Last summer, though, Stone Barns Center announced it was creating its Chef in Residence program and that the restaurant kitchen would be turned over to a series of visiting chefs as a way to strengthen and expand its community—and to tackle racial and gender inequities in the restaurant industry.

“It’s not just a back and forth—it’s a back and forth and a back and forth and a back and forth.”

—Gregg Moore

“Blue Hill and the Stone Barns Center together are very much this synergistic community of cooks, farmers, scientists, producers, artists, and others. We started the Chef in Residence program to extend this community outward, knowing that we need fresh voices and diverse perspectives to create an eating culture that supports and encourages the right kind of farming,” says Barber. “Each resident chef initiates a reimagined community through intimate collaborations with our bakery, our butchery, and with artists like Gregg.”

Back to the Land

The chef-ceramist collaborations that have taken place this year through the Arts & Ecology Lab at Stone Barns Center are not Moore’s first. Before working with Tate, Victoria Blamey, Shola Olunloyo, and Johnny Ortiz, Moore teamed up with Barber. Back in 2014, Moore read The Third Plate: Field Notes on the Future of Food—Barber’s seminal book about food, farming, and sustainability—and was struck by the synergies between Barber’s process and his own.

“There are so many connections between my practice in the studio and Dan’s process in the kitchen. There was hardly a page in the book that wasn’t dog-eared or had Post-its stuck to the page,” says Moore. At the most elemental level, Moore says, both he and Barber use heat as a transformative ingredient: “It takes materials and turns them into objects on my end, and it takes ingredients and turns them into food on Dan’s end.”

The landscape at Blue Hill at Stone Barns in upstate New York. Photo by Alice Gao.

“Gregg visits the farm, spending time with the animals, walking through the fields, immersing himself with the same voracity that I do as a cook.”

—Dan Barber

Moore, who is a professor at Arcadia University and studies the intersection of agriculture, ceramics, and cooking, reached out to Barber with an idea: Why stop at food when it comes to the farm-to-table ethos? Why not craft dishware that also draws on the materiality of the farm landscape? Barber was instantly sold.

“Gregg made me realize that we were thinking about the food—the way it’s grown and raised and everything that goes into the creation of a plate—but ignoring the plate itself,” Barber says. “I was ignoring the raw material of our plates while obsessing over the raw materials of our food.”

Since 2015, Moore and Barber have collaborated on a number of dishes, starting with the foundational Chef’s Plate, a black porcelain plate with a stonelike appearance. “It was a new challenge for me because I hadn’t made pottery for restaurants—ever,” says Moore. Not only did it have to be very durable, he explained, but, most importantly, it could not upstage the food.

Moore and Barber’s ceramic collaborations range in tone from whimsical to jaw-dropping, but they’re always inspired by the farm at Stone Barns Center. For example, a trio of plates called Grazing, Pecking, and Rooting were all made with the assistance of various Stone Barns animals.

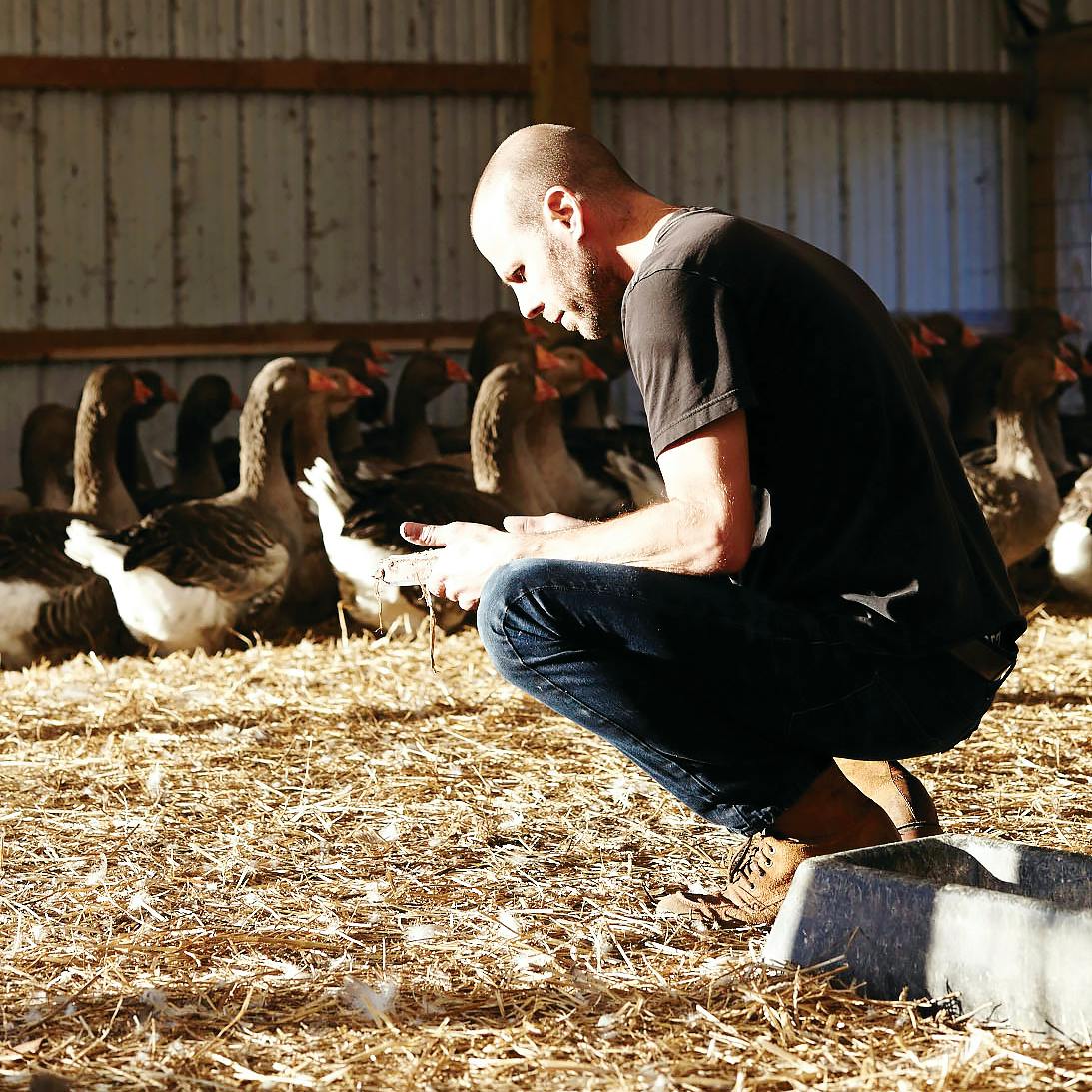

_Photo+by+Andrew+Scrivani.jpg?fit=crop&ar=1:1&auto=compress&cs=srgb)

LEFT: Moore with Toulouse geese. Photo by Jochem Van Grunsven. RIGHT: Impressions left by the geese appear on the Pecking Plate. Photo by Andrew Scrivani.

For the Grazing plate, Moore actually grew grass in a raw clay plate so that Stone Barns sheep could eat off of it. He then used the plate, which was marked by impressions from the grazing sheep, as a mold to make a ceramic version. Barber used the final black porcelain plate to serve a dish of sheep’s cheese coated in biochar, with melon and carbonized sheep bones. The Pecking plate, a black porcelain plate with surface texture formed by geese eating feed, was used to serve two fried chicken’s feet. When Moore made the Rooting plate, the Berkshire pigs that ate off the clay plate were so gung-ho they destroyed it before Moore could bring it back to his studio. Barber used the final version, a black porcelain plate marked by pig-snout impressions, to serve a tiny tart filled with various foods pigs forage.

+%2B+tart+made+from+everything+a+pig+eats_Photo+by+Andrew+Scrivani.jpg?fit=crop&ar=1:1&auto=compress&cs=srgb)

LEFT: Berkshire pigs leave their mark in clay that Moore later uses as a mold for Rooting Plates. Photo by Jochem Van Grunsven. RIGHT: Pig tart with foraged greens and sumac served on a Rooting Plate. Photo by Andrew Scrivani.

“One of the more exciting parts of this whole process for me is coming up with some admittedly strange things to call plates and seeing how Dan runs with it,” says Moore. “It takes looking through a different lens . . . to activate these with food.”

Another collaboration is the Single Stone Plate, a gorgeous stoneware plate glazed with a single fieldstone from the Stone Barns farm. It came about because Moore was looking for a “ceramic analog” to Barber’s famous “single-udder butter”—butter made from the milk of a specific cow. As he walked around Stone Barns, Moore noticed a large stone near the top of the vegetable farm. Moore has a background in geological science, so he was pretty sure that, if processed correctly, the stone would turn into a glaze. His hope was that plates glazed with a single stone would “speak to the locality of the geology of the farm in a way that the butter speaks to the biology of the cow,” he says.

Moore brought the stone back to his studio, fired it, crushed it with a sledgehammer into the texture of sand, and then used a machine called a ball mill to pulverize the sand into a liquid—the resultant glaze which he sprayed onto a plate and fired.

“I got about 100 plates out of the glaze and then it was gone,” Moore says. He had no idea how the richly plum-colored plate would be used, but Barber eventually served eggplant on it, cooked in a bright green turmeric leaf.

_Courtesy+of+Gregg+Moore.jpg?fit=crop&ar=1:1&auto=compress&cs=srgb)

+Plate_Photo+by+Andrew+Scrivani.jpg?fit=crop&ar=1:1&crop=focalpoint&fp-z=1.3&auto=compress&cs=srgb)

This Single Stone Plate is used to serve Chef Barber’s Choryoku eggplant cooked in turmeric leaf. The plate’s glaze was made from breaking a single fieldstone found on the farm with a sledgehammer. Plate photo by Andrew Scrivani. Fieldstone photos by Gregg Moore.

“What I really value in this relationship is that it’s not monodirectional,” Moore says. “I think the word collaboration gets misused way too often these days, and that people are probably more speaking of a commission than a collaboration. The Single Stone Plate is a good example of our deep collaboration—me coming up with an idea inspired by his idea of the butter and then giving it back to him to think about how to use it. It’s not just a back and forth—it’s a back and forth and a back and forth and a back and forth.”

Barber agrees: “The truth is, our collaboration is rooted in the same philosophy as the Blue Hill menu at large—it all starts with the farm. I don’t present Gregg a carrot dish and ask him to design around it, nor does he come to me with a certain aesthetic that I then cook towards. Gregg visits the farm, spending time with the animals, walking through the fields, immersing himself with the same voracity that I do as a cook.

“That’s the magic of Gregg’s work—it captures the textures, flavors, and visuals of the landscape inspiration before it does any individual dish.”

Collaboration, Not Control

That was certainly the case when Moore collaborated with New Mexico chef Johnny Ortiz on earthenware plates that were coated with terra sigillata made from Stone Barns Center farm soil, pit-fired on the farm, and coated with grass-fed beef tallow. The landscape was also the main influence when Moore collaborated with Chilean chef Victoria Blamey on a series of ceramic dishes inspired by the Chilean coast: the glazed porcelain Coast Plate, the glazed stoneware Kelp Plate, and the porcelain Mussel Bowl with interior glaze.

TOP: Chef Johnny Ortiz and Moore firing plates at Stone Barns Center. The earthenware plates are coated with terra sigillata—a refined clay slip—made from farm soil, then pit-fired and cured with tallow from grass-fed beef cattle. Photos courtesy of Blue Hill at Stone Barns. ABOVE: Ortiz’s horno short rib with red chile and tsa tsai mustard greens served on one of the plates. Photo by Elena Wolfe.

Moore, who spent a semester in southern Chile 25 years ago, remembers cooking giant mussels on the beach and paddling through dark, oily kelp forests. “Working with Victoria was very meaningful for me because I have not been back to Chile since college,” Moore says. “The collaboration was like an invitation to travel back through Victoria’s cooking and through object-making for her residency.”

The sky-blue Coast Plate, inspired by the 4,000-mile-long Chilean coastline, is very long and narrow and has sand embedded along its length to represent the beach. At one point, Moore was concerned the plate was too narrow to be functional, so he called up Blamey and said he would make it wider.

“I said, ‘Just make the plate how you want to make it, and I will find a way to make sure I can plate something there,’” Blamey recalls. “This residency is also about showcasing what he’s doing. He’s an artist, and I’m an artist collaborating with him, so this collaboration has to meet in the middle, you know?”

This narrow porcelain Coast Plate—its glaze embedded with silica sand—is paired with a narrow dish: sugar kelp with a shiitake mushroom coating. Photo by Elena Wolfe

Blamey ultimately used the dish to serve sugar kelp stipe with rhubarb and turnip kraut. She had always wanted to do a dish with stipe—the long stalk of the seaweed plant—since she learned from Chilean seaweed farmers that there was only a market for the leaves of the plant. When she learned that she could get sugar kelp stipe from a Maine-based farm, she thought, I have the perfect plate for this.

“It was a very organic, natural process collaborating with Gregg,” Blamey says. “What I loved about collaborating with Gregg is that he is very feminine in his approach. It’s not just a rational, straightforward conversation—we talked about symbolism and creation and the origin behind the dishes I was working on. I think he has an incredible capacity to put himself into whatever it is that you are trying to express.”

This porcelain Mussel Bowl with interior glaze, a collaboration of Moore and Chilean chef Victoria Blamey, was used to serve cholgas secas, a mussel dish. Photo by Elena Wolfe.

Chef Shola Olunloyo agrees. “Working with Gregg was very symbiotic,” says Olunloyo, who makes modern Nigerian food. “We would have conversations about the culture of eating in Nigeria, both in public and in home, and he would literally translate my ideas into tactile objects within forty-eight hours. I’m like, ‘Dude, do you have, like, fifty elves making these things?’”

From Moore’s perspective, he actually embraces the loss of control that comes from collaborating with others. His work is not final when it leaves the studio, he says, because he gets to see how it will actually be used—or “activated,” as he puts it—by the chefs, servers, and diners at Stone Barns, and that can change his process.

Nigerian chef Shola Olunloyo’s roasted carrots, coconut, toasted nuts and grains, and oxalis sorrel on a plate made of iron-stained stoneware. Photo by Elena Wolfe.

“I get to watch Dan cook a lot and see him plate, and that informs a lot of what happens back in the studio,” Moore says. “Watching him use the plates that I’ve already made, I can learn about how to make the next plate better. I can make the most brilliant plate in the world, but if he doesn’t grab it to use it, it’s useless.”

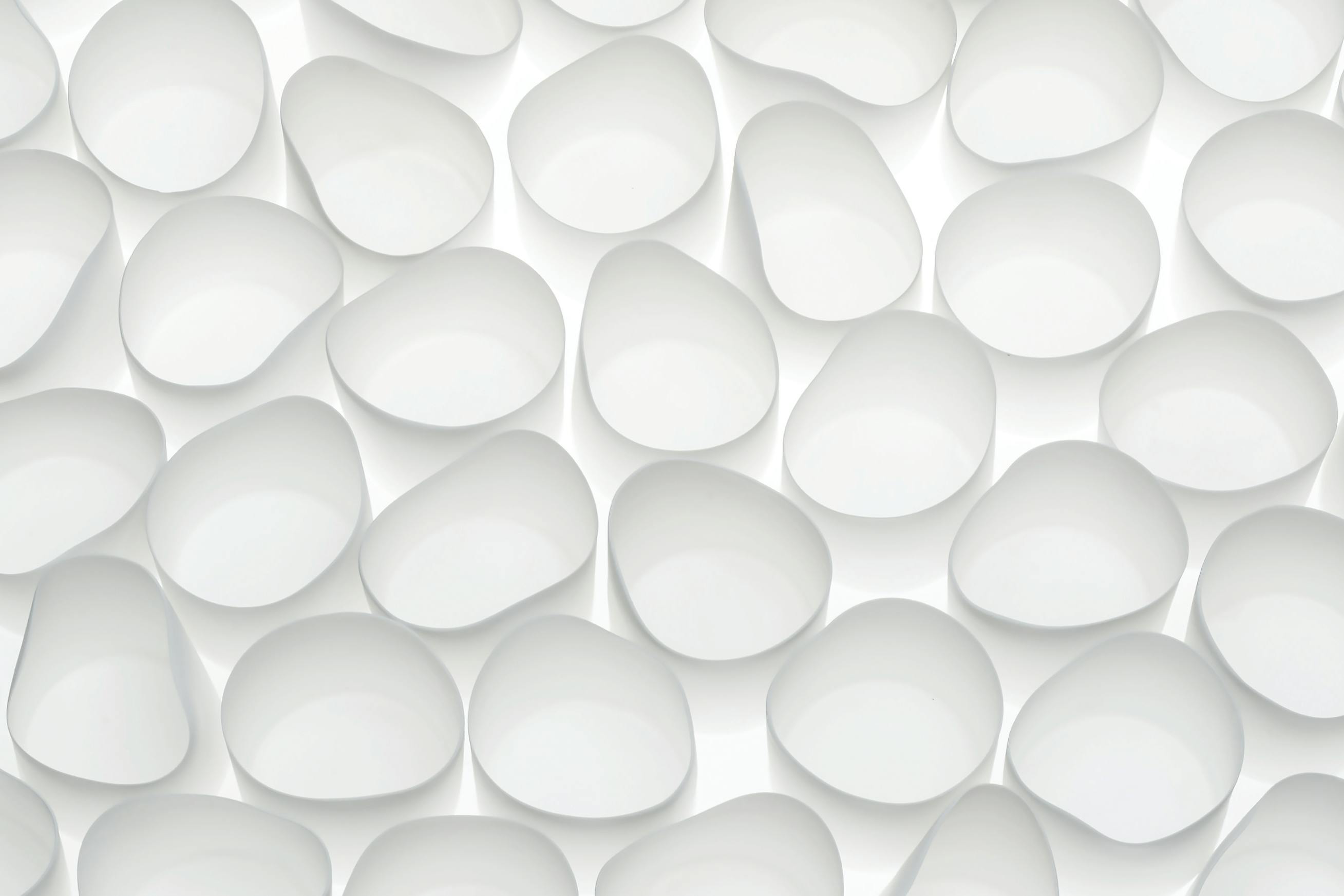

Holding Health in Your Hands

It was a conversation with Barber that led to their flagship collaboration—bone china made from the bones of Stone Barns grass-fed cows. After a late-night kitchen chat with Barber, Moore says, “I remember driving really fast home that night to see if I could make bone china out of these white bones.” The resulting plates, bowls, and cups are both astonishingly white and translucent and very strong. For comparison’s sake, Moore made a dish using bones from industrially raised, grain-fed cows and discovered that the resulting dishware was much more brittle and not nearly as white. Based on his discovery, Moore is working with an evolutionary biologist on a study of the effects of farming practices and animal husbandry on the material properties of bone china.

Moore discovered that these delicate bone china cups—made from the bones of grass-fed cows—are whiter and less brittle than those made from grain-fed animals. Photos courtesy of Gregg Moore.

“In essence, Gregg’s bone china is physical proof about the health and ecological qualities of good agriculture,” says Barber. “That diners can hold that in their hands is a powerful experience.”

Moore is currently overseeing more chef-artist collaborations and is planning to exhibit his collaborative ceramic pieces this fall as part of an exhibit showcasing work from the Chef in Residence at Stone Barns program. He and Barber are also continuing their artistic partnership, a relationship for which Barber is endlessly grateful—especially in this era of Instagram #foodpics.

“It’s actually always been an insecurity of mine because photos of my food tend not to show that well compared to what chefs are doing today,” says Barber, whose deeply complex food can look deceptively simple. “The artistry of Gregg allows me to achieve the kind of beauty that I otherwise would not have had as clearly without them. What the plates have done for Blue Hill is profound.”

stonebarnscenter.org | @stonebarns

greggfmoore.com | @greggfmoore

Discover More Inspiring Collaborations in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.

This activity is made possible by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund.