Mountain Meets Modern: Knoxville, Tennessee

Mountain Meets Modern: Knoxville, Tennessee

At the edge of the Smoky Mountains, craft thrives with an Appalachian heart.

As a southern city, Knoxville has its fair share of sweet tea, folks who say “Bless your heart,” and the thick humidity that the region is known for. Still, the artisan scene perhaps identifies more with another, overlapping label: Appalachian, and all that implies – fortitude in tough times, a deep connection to the land, and a fierce sense of independence.

Founded as a fort on the trans-Appalachian frontier, Knoxville today is the western gateway to Great Smoky Mountains National Park and within striking range of two major destinations poised to propel Smoky Mountain heritage through the 21st century.

Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts, located just outside the national park, has long been renowned for both its craft education as well as its advocacy. Highlights of the 102-year-old organization’s dedication to local artists include its pivotal role in founding Gatlinburg’s Arrowcraft Shop. The store first served to help mountain families by selling their handicrafts; shoppers can continue to buy fine craft curated by the Southern Highland Craft Guild.

Blackberry Farm, in Walland, Tennessee, is much newer to the scene. The luxury inn and farmstead promotes the region’s heritage, employing artisans to produce small-batch goods ranging from honey and aged cheeses to delicacies such as pickled ramps and even beer. The farm has also published two cookbooks, one dedicated to seasonal cuisine and a second the organization describes as a mix of “recipes and wisdom from our artisans, chefs, and Smoky Mountain ancestors.”

About 30 miles from the farm, Knoxville is a thriving modern city of around 180,000, complete with karaoke bars and downtown parking headaches. Yet its craft scene retains traditional mountain virtues, emphasizing hard work and individualist tendencies, and an appreciation for nature. The latter is embraced by sculptor Kelly Brown, a seasoned rock climber whose public art uses materials such as tree limbs. His magical “twigloos” can be seen at the Ijams Nature Center in South Knoxville.

Richard Jolley perhaps best exemplifies the region’s ingenuity. Jolley moved to the Knoxville area to start a glass workshop in the 1970s, and his industrious creativity and sheer determination have won him international acclaim. “It’s as if someone suggested, ‘Let’s pick the most dangerous, most difficult medium to work with – how about glass?’ ” says David Butler, a close friend of Jolley and the executive director of the Knoxville Museum of Art. “Richard wants glass to do things that nobody knew it could, that no one else ever thought of.”

To get a true feel for the range of art that thrives here, however, one must zig and zag to various galleries and workshops, and traverse the city.

Downtown

Knoxville’s art scene is anchored by the downtown Knoxville Museum of Art, which has bolstered its mission in recent years to promote East Tennessee artists. That includes the 2014 unveiling of Richard Jolley’s Cycle of Life, a huge assemblage of thousands of individually blown and cast glass elements in the museum’s Great Hall, now known as the Ann and Steve Bailey Hall. Butler describes it as “a 7-ton argument that East Tennessee is a place where important things happen in the visual arts.” The work, several years in the making, helped the museum in its successful $6 million capital campaign to renovate the building. The museum has also begun expanding its contemporary glass collection, including many works from regional artists.

A similar effort to celebrate regional culture is at Pioneer House, a boutique, art gallery, and printmaking studio just a brisk 15-minute walk away, in the heart of Knoxville’s downtown Gay Street corridor. Owner Julie Belcher describes the clothing and accessories for sale here as “contemporary honky-tonk” and “hillbilly vintage” – fancy cowboy/Western wear with elaborate embroidery and, often, lots of fringe. Oversize letterpress postcards boast folksy slogans such as “I Love You Like Biscuits & Gravy” and “Butter My Butt and Call Me a Biscuit.” Both are popular when Knoxville’s premier foodie event, the International Biscuit Festival, makes its appearance each May.

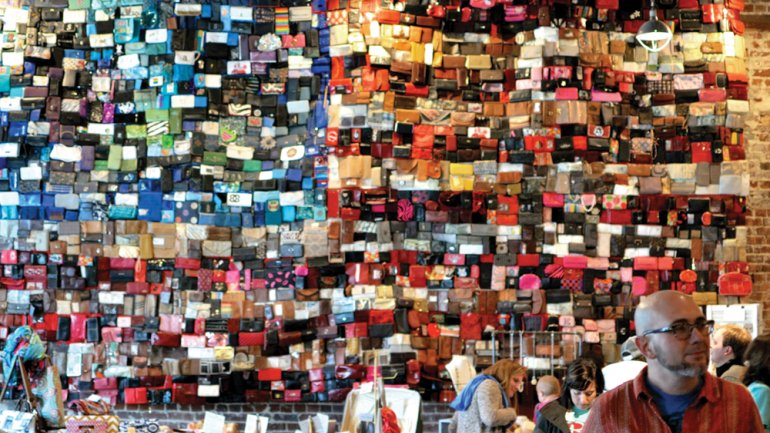

Not far away is the Emporium Center for Arts & Culture, a cornerstone of Gay Street with a rich history of its own. Built in 1898 as the original home of the prestigious Sterchi Brothers Furniture Company, the building went through various incarnations, then sat vacant for many years until its renovation in 2004. It now hosts two art galleries featuring regional artists, 10 artist studios, and offices of the Arts & Culture Alliance, as well as other arts and cultural organizations.

Bearden

West Knoxville’s Bearden neighborhood is a bustling commercial corridor that’s home to craft destinations such as Liz-Beth & Co., founded by Liz Gobrecht, with son and daughter Bart and Beth Watkins, in Liz’s mother’s basement more than 20 years ago. In addition to serving as a custom framing and fine art printing shop, Liz-Beth & Co. has carefully cultivated work from a wide range of artists, including regional artists such as ceramist Buie Hancock, glass artist Daniel Pacific, and jeweler Dale Armstrong.

Bennett Galleries is just a few miles away, located in a 35,000-square-foot former cinema. Started by Rick Bennett in 1976 and now run with his wife, the gallery was one of the first shops to sell works by Jolley, and it still offers some of the smaller works that have garnered the glass artist worldwide acclaim. The gallery also represents glass artist Tommie Rush, whose vividly hued, lyrical vessels are in the Smithsonian collection; Rush and Jolley, who are married, were the subjects of a summer show at the gallery.

A more recent entry into the neighborhood is the District Gallery & Framery, founded in 2011 by East Tennessee natives Jeff and Denise Hood.

North Knoxville

The northern fringe of downtown is home to Ironwood Studios, the brainchild of artists Preston Farabow and John McGilvray. Longtime friends, McGilvray and Farabow bought the warehouse together several years ago to house each artist’s business; one half of the building hosts Farabow’s design house and metal fabrication shop, Aespyre, and the other side hosts the eponymous McGilvray Woodworks. Farabow also makes art from the wreckage of banged-up race cars, once even on the grounds of the Daytona 500 race track while a race was in progress. (He had permission.)

Not far from Ironwood Studios is the home of the Retropolitan Craft Fair, in a newly recognized historic district known as (no, really) Happy Holler. Organized by Alyssa Maddox and three other local makers, the group’s first show this past spring drew more than 400 attendees and included vendors from around Tennessee, as well as from North Carolina and Alabama. Maddox says the plan was to create a thoughtfully curated show of indie craft and design, drawing on top Southeast artists and mixing in upcycled goods. The reality for craft lovers regionally: A new generation of artisans has hit the Knoxville scene, and they will not forget the past.

Rose Kennedy profiles artisans for Knoxville’s Metro Pulse.