Mozart in the California Desert

Mozart in the California Desert

When the New York-based designer Marsha Ginsberg was brought on to create a set for Mozart's opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio) for Theater Basel in Switzerland, she had a problem most people would love to have. "Everything was made too well," she explains. "The shop was too good!"

Working with the American director Christopher Alden, Ginsberg was charged with bringing Mozart's 1782 tale of exile up-to-date for a performance in the fall of 2007. The pitfalls that she encountered were a twist on stories we are all too familiar with in too many facets of life-shoddy workmanship and little care for craft.

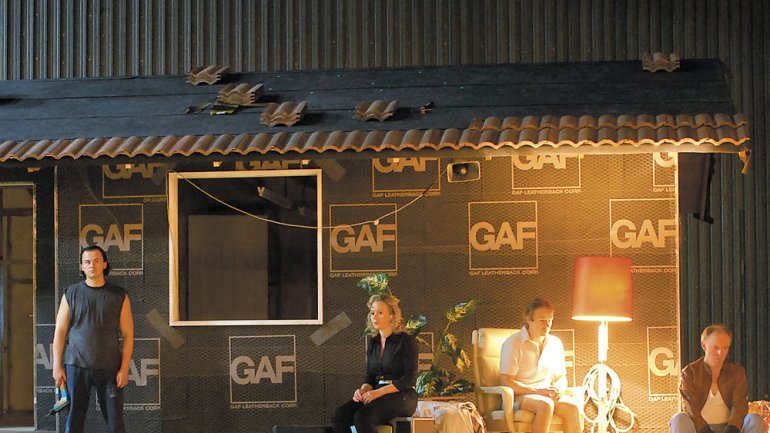

Alden and Ginsberg's directive called for Mozart's story to take on a post-9/11 glare-the two Muslim characters in the opera, Osmin and the Pasha, have been transplanted to the California desert, where they have taken up residence in an abandoned house in an abandoned subdivision. Ginsberg took inspiration from John Divola's photographs of areas around the Los Angeles International Airport. She aimed to give the opera that same strange aura of isolation, desolation and desperation-feelings that would reflect the unresolved, complex emotions of the characters-especially the two sets of lovers toward one another. "The main set was a house that was in mid-construction but hadn't been touched for close to 10 years," Ginsberg says. "We needed it to look bad!"

To the stage technicians she'd be working with, however, the idea of poor workmanship was something more difficult to translate than Ginsberg's self-proclaimed broken German. "Everyone in the shop just looked at me in dismay," Ginsberg says. "They understood what I was asking for, but they were shocked I would want such a thing. More than that, I think they were perturbed that they were expected to make something badly."

In Europe, there is a healthy competition among the various opera and theater companies, and to the team at the Basel shop, the idea that their stage work would be represented by a house that was supposed to be in terrible condition was an affront to their refined sensibilities. However, working with such a skilled group meant that the set, even in its appropriately dilapidated form would take on a certain air of dignity. "The quality of the building was amazing," Ginsberg says. "It was somewhere between a stage set and a real house, except many parts, like the lap joints, were far superior to what you'd find in most houses."

The way the shop in Basel operated was quite different from anything Ginsberg had experienced, mainly because it is highly unusual for a company in the United States to have such an expansive scene shop attached to it. Though the Metropolitan Opera and the San Francisco Opera do have shops-as do many regional groups, though on a much smaller scale-it is becoming increasingly rare as financing becomes harder to secure. In Europe, the shops are still state financed, resulting in a system that allows not only young designers and directors to gain firsthand experience with opera production, but young woodworkers, welders, lighting designers and other technicians as well. This nurturing of talent ensures a steady stream of high-quality productions and contributes to making opera a significant force in contemporary culture.

So, with all the time, effort and skill that went into this production of Il Seraglio, how was it received? "Bringing operas into the present day always will have its detractors," Ginsberg says. "When we staged Carmen together in Mannheim and put it into a modern context," Alden, the director explains, "there was quite an uproar." "It was a success," Ginsberg says, "in that everyone was talking about it for weeks." But what about Il Seraglio? "Some people were confused, but we received a lot of reviews, and I think most people were pleased with the presentation." Regardless of the audience and critics' reaction, one thing is certain. The opera in Basel will always have a sound, sturdy and striking structure to set the stage.