In My Father’s House

In My Father’s House

Whenever I give an artist’s talk, people inevitably ask me about my father, the acclaimed studio jeweler Earl Pardon, who died in 1991. They ask, “How did he influence you?” My answer often surprises them: Both my parents influenced me, but I learned more about art from my mother than my father.

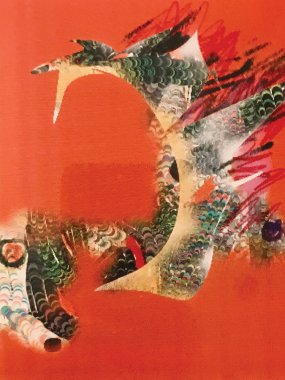

Like my father, my mom, fiber artist Eunice Pardon, taught for more than 35 years at Skidmore College. And though my father was celebrated for cleverly combining enameled silver chips of many hues in his jewelry, it was my mother who taught me about color – the push-pull, how to use it, and how to make it pop. She knew a lot about color and juxtaposition and worked with materials others wouldn’t think of. She was always experimenting. She’d go into her studio and make these magical little things that were never finished, and I loved that. I found her work exciting. That was true when I was a child and still true at the end of her life, when her arthritis got so bad that she had to give up fiber work. I set her up with a paint program on the Mac, and we collaborated on print projects until she died in 1997.

How could I grow up with Earl Pardon and not be shaped, even transformed, by the experience? Of course, I was. That’s true even though for a long time I wanted nothing to do with jewelry; I was a painter. But as it turned out, in my 30s, I ended up working side by side with my dad for four years, before a heart attack killed him at age 64.

My relationship with my father was complicated. I think about that often these days, as I watch my own son, who’s 20, learn and grow as an artist. The relationship between parent and child is like that between teacher and student – but sometimes, whether or not it’s acknowledged, the child is the teacher. I’ve learned as much from my son, Dexter, as I’ve ever taught him. Being a parent is a matter of subtle, constantly shifting give-and-take.

That’s true even when the parents are professional teachers, like mine. I remember watching my father in action in the classroom when I’d visit as a kid. He always encouraged his students. “Oh, look what you did there. See? This is a good move,” he’d say. And “Well, if you have this line here and bend this line …” and “Five is better than four” – all those classic design things. He was funny. He was always joking with them, and his students loved him.

I remember the envy I felt, because he didn’t talk to me that way. Instead, when I’d bring home work from high school, he’d shake his head, concerned. “Oh, boy,” he’d say. He couldn’t compliment anything I did. Instead, he’d correct me. “Look,” he’d say, “this is what you need to think about when you’re thinking about this.” And he’d pull out a book of Picasso and show me line drawings, and say, “Look what this man did. He’d take this line, and he’d chop it here, and he’d bring it over here, way on the other side of the paper.” He wanted me to learn the important structural things.

Seeing him with his students and then experiencing him at home, I was amazed at how almost Jekyll-and-Hyde he was. Even as I matured and made my way through the painting program at Alfred University and on through graduate school, he never told me directly if he thought I was doing well or if he liked a piece I’d made. I would always hear later, from my mother, that he did. He was a hard one.

That’s why I knew it would be difficult working alongside him, as he proposed I do in the mid-1980s. I didn’t know much about metals or jewelry making at the time. I knew he wanted to teach me and pass on his knowledge, his legacy. And maybe he wanted an assistant to do his bidding, too. So I entered into an apprenticeship with the great Earl Pardon, and it was an old-fashioned apprenticeship. I started out cleaning, organizing, doing menial things. Earl frowned on sick days and vacations. I had one week off each year for the first several years. Eventually he trusted me to make hundreds of the little enamel chips for his mosaic-like pieces – which was laborious, to say the least. As I was producing all of these parts, I figured out better ways to make them, speeding up the process, doubling his production, and freeing him to focus on his signature brooches. Within the first year, I was making more than just parts – I made earrings, cuff links, and then bracelets.

I was his assistant, but I also tried to be a one-man OSHA for Earl. In the studio, we put jewelry in acid baths, and did enameling, soldering, and polishing, but there was hardly any ventilation. And this was a guy who smoked three packs of cigarettes a day. I had to go outside regularly just to breathe. He wouldn’t listen, though. It wasn’t until after he died that I was finally able to put in proper ventilation.

Over time, in that rank space, our relationship evolved. Gradually, as we worked side by side, we learned to relax around each other. We could be silent and not feel pressure to chat. Eventually, we started talking. And Earl had things to say – about his life, World War II, the early years of the craft movement, old girlfriends. (Who gets to talk to their dad about old girlfriends?) We learned to appreciate each other’s experiences. We became friends. I had four great bonding years with him as a person, rather than as a dad. To this day, I treasure that time.

Earl never got to meet Dexter. But my mother did. We adopted him in 1997, when he was 3 days old, and my mom got to be with him for 10 days before she died, delighting in being a grandmother.

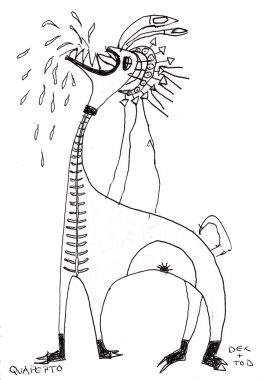

As Dex grew up, he and I were always drawing together. We made our own games and Pokemon cards. I made him a jeweler’s bench in the studio when he was about 4, and he would make jewelry out of silver scrap and sell it to his obliging aunt. One day, I remember, instead of drawing his own figures, he tried to re-create a drawing of a superhero he’d seen. He was actually crying because he couldn’t get it right.

Now, here’s the difference between my father and me: Forty-five years earlier, if I’d been the distraught budding artist, my dad would have sat me down and had me break up the figure into spheres, cones, cylinders, and correct proportions. My approach was different. “Why on Earth would you want to restrict yourself to someone else’s superhero drawing?” I said to Dex. “Think of all the possibilities you’re giving up by doing that. Make your own superhero; it can be anything in the world.” Dex thought about it and then drew in his room for an hour. When he came out, he had a pile of drawings. The best was Lamp Man, whose power was to help kids read. My wife, Jackie, and I still have some of those drawings.

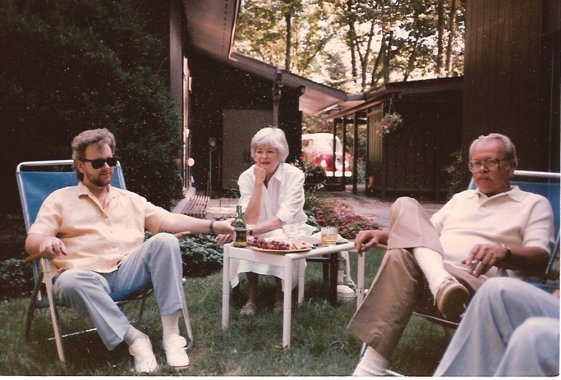

I think about my parents every day. Jackie, Dex, and I live in their home – the Techbuilt house that architect Carl Koch designed in 1960. My parents and I moved in when I was 8. All around me today are the echoes of my childhood: the wooded area in Saratoga, ideal for exploration; the studio I built with my dad in 1974, when I’d graduated from Alfred, and that I later rebuilt; the white stones I had ringed around an old oak (which my son, at age 3, dubbed the Family Home Rock Place). I remember playing with his tools and exploring my father’s materials, digging through the drawers, seeing all the semi-precious stones and things he’d collected. It was like treasure. I still have a collection of my father’s work, and I still repair his pieces for collectors and handle his business affairs.

Artistic collaboration is special, especially with your parents. It transcends the mundane and binds you through love and respect. When Dex was about 4, I called back all of my work from the galleries to do an inventory. On the floor, I lined up dozens of pieces, work from 1983 to 2000, chronologically. Dex sprawled out, examining each one. “Which pieces did Grandpa Earl see?” he asked. There weren’t many before 1991, because most had sold by that time. He looked at the long line of newer pieces and said, “Wow, he would have been proud of you.” As I watched him head off to play, I smiled.

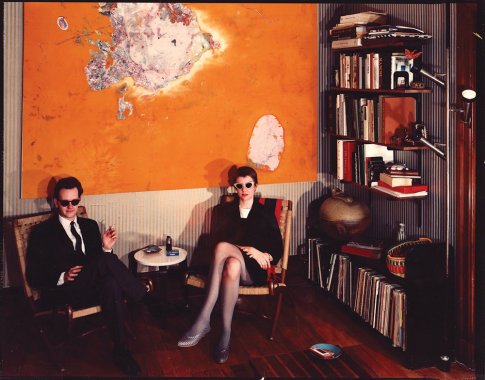

Tod Pardon is an artist in Saratoga Springs, New York.