Natural Metalsmiths

Natural Metalsmiths

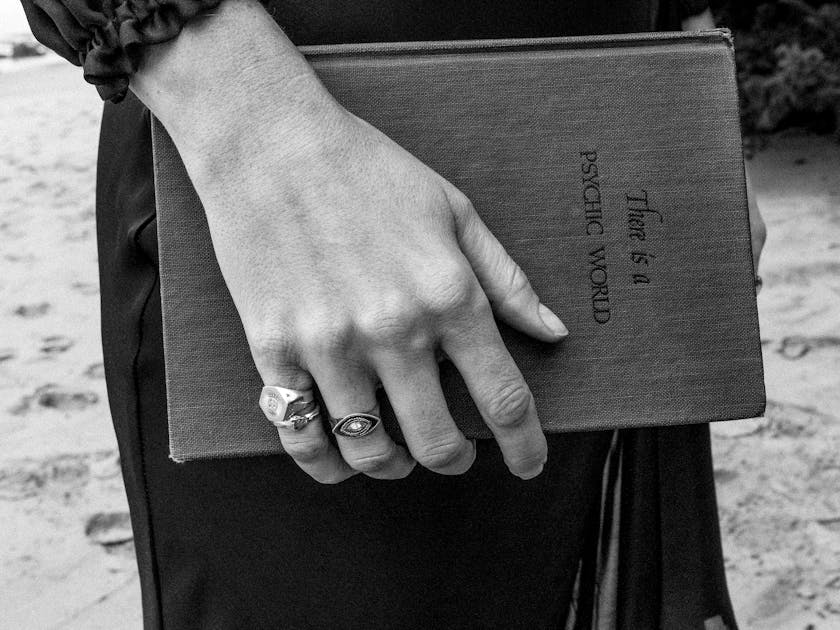

↑ Many of the granules on this Slither Band ring made by Loren Nicole Teetelli are smaller than a pen point. A former archeologist, Teetelli employs ancient techniques in her goldsmith practice.

Photo: Courtesy of Loren Nicole

Beetle wings and victorian mourning jewelry. Gleaming ancient Egyptian gold and Viking treasure. Medieval coats of arms and family crests. Mussel shells and spruce-stitched copper. You might expect to find this list in many major museums around the world. You will also find these things in the studios of four jewelry designers working today.

For some of these jewelers, following the practices of the past links them to a deeper history of makers. For others, seeking personal connection through design is the ultimate joy. But all of them, through the materials they use in their studio practice and stunning designs, create beauty that’s meaningful to wear.

↑ Jennifer Younger's Raven and the Sun, a mussel-shell sculpture, includes formline engravings of Raven and Sun inside the

shell. Formline is a 2,000-year-old practice involving curving lines that widen and narrow.

Photo: Caitlin Fondell

Ancient Methods, Modern Makers

Tlingit jeweler Jennifer Younger shapes, polishes, and hand-engraves every piece she creates in her Sitka, Alaska, home and studio – from bangles depicting Sitka’s wild roses to silver disc earrings made from tanned sockeye salmon skin to copper mussel-shell pendants with a blue patina. Younger specializes in silver and copper engraved with Northwest Coast Native formline style and incorporates materials from nature in her work. She likes designing motifs that anyone can wear, but respectfully leaves out sacred patterns or animal designs belonging to tribal clans. “I see my work as an entry point for [non-Native] people who appreciate formline and want to support Indigenous makers,” she says, “And that helps me feel stronger in my Tlingit identity, but also as an artist.”

At its most basic, “formline” refers to curving lines that widen and narrow “almost calligraphically,” Younger says. The artistry is in balancing formline ovoids (oval-like shapes), U-shapes, and S-shapes as positive and negative spaces to create an image or pattern.

Formline engraving is a continuation of Younger’s efforts to reconnect with her heritage through art – work that began because of her grandmother. “She was Tlingit at a time when it was especially bad for Native people,” Younger says. Her grandmother was taken from her family as a child and sent to a white boarding school. Like generations of Native children in the 19th and 20th centuries, she was forced to forget her culture – her language, dances, music, everything.

Her grandmother and her grandmother’s children were outsiders to both the white community in Alaska and to the Tlingit. Younger and her mother have found reconnection to their culture through artmaking, starting with spruce-root basketweaving, a complex weaving practice among the Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, and other tribes. Later, she earned a grant to apprentice with Tlingit-Unangax artist Nicholas Galanin and his father, Dave Galanin, a Tlingit silver- and wood-carver. Both are experts in the Northwest Coast formline style.

Though this style is a 2,000-year-old practice known for its strict rules of form and balance, Younger finds freedom in its structure. Early on, she says, “I would ask Dave: ‘Have you ever seen a formline spider?’ And he would say to me: ‘Why don’t you make it and see?’ ” As long as you are true to formline style, there are no limits to what you can depict: “That realization really felt like the world opening up to me. I still can’t get enough.”

↑ While working on a project related to Standing Rock, Younger created this Water Is Life bracelet, which combines Tlingit and Lakota floral and seaweed beading patterns.

Photo: Caitlin Fondell

Silver is widely used by Native jewelers, says Younger, but copper holds her special fascination. It was an important material to Alaska Natives well before European and American ships brought it to the region to trade, she explains. “Coppers” or Tináa to the Tlingit, are shield-shaped copper sheets wielded by chiefs as a sign of power and wealth. The materiality of historical copper is something Younger finds especially striking. The tears, patches, bends, tarnish, polish, and patinas – all the ways that copper behaves and can be manipulated – are something she continues to explore in her work. “The patina – the effects you can get from copper – keeps it interesting and chaotic,” she says. “Add heat, add chemicals, add time, and you never know what will come out!”

“I would ask Dave: ‘Have you ever seen a formline spider?’ And he would say to me: ‘Why don’t you make it and see?’”

~Jennifer Younger

Thousands of miles south of Younger’s studio, in Hermosa Beach, California, Loren Nicole Teetelli also draws on an ancient alloy in her goldsmith practice. Teetelli’s third collection, Nebu: Sands of Gold, is inspired by Egyptian dynastic jewelry – right down to the goldsmithing techniques. Think long torpedo earrings with vibrant drop gems, wide granulated-gold rings, and a truly impressive pink fresh-water pearl and gold multistrand necklace. “My goal is to use ancient techniques to craft eternally modern pieces,” she says.

↑ Teetelli sought out experts to learn ancient goldsmithing techniques. She uses materials, like a 22k gold alloy, closest to what the ancients used.

Photo: Austin Harris

Teetelli started her career as an archaeologist and later worked as a conservator for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s African, Oceanic, and Ancient American Arts collection. To better understand the pieces she was caring for, she decided to learn how they were made. Teetelli, who has no formal training in jewelry making or metalsmithing, sought out experts in methods closest to those of early artisans. Goldsmithing came naturally to her, she says, and it was so fulfilling creatively that what began as a project in experimental archaeology became her full-time career by 2016. Her business is called Loren Nicole.

↑ Depicting two hippos from an ancient Egyptian legend, this Horus Will Be King is made using the processes of chasing and repoussé.

Teetelli textured this ring using an antique Roman hammer.

←

Photos: Courtesy of Loren Nicole

“It’s like magic every time,” Teetelli says of repoussé and chasing – specialties of hers – in which flat pieces of malleable metal are hammered on one side to create a design in relief on the opposite side. Teetelli, too, makes every piece by hand. She also works in age-old granulation and cloisonné techniques, preferring a 22k gold alloy closest to what the ancients used. While slower, her processes afford her a close and intimate control over her work, something that she finds calming. “I actually don’t know how to make jewelry any other way. I didn’t learn the modern techniques and processes,” she says, “But I like what I’m doing – there’s a quietness to it.”

Beauty in the Unexpected

Like Younger’s experiment-ations in copper and Teetelli’s ongoing homage to gold, Chicago born-and-raised Alicia Goodwin values interplay of texture and the unexpected in her jewelry line, Lingua Nigra. The name means “black tongue,” actually derived, she says, from a rare disease meaning “black hairy tongue.” It’s appropriately unconventional given the broad sources of inspiration that Goodwin draws from, which include natural history, entomology, macabre Victorian culture, and her travels around Central and South America.

Goodwin works mainly in gold-plated brass (or sometimes nickel or zinc) casting each piece from the mold of a hand-tooled, acid-etched prototype. Many designs start from a large sheet of reticulated brass that she has been working through for years. She looks for interesting shapes or textures that mimic something in nature. She might even finish a piece with natural materials, such as dentalium shell or iridescent beetle wing (technically, the outer shell covering the delicate wing). The latter, Goodwin says, is so vivid that people often mistake it for enamel.

↑ This Rough Smoke Etched Cigar Band is carved from wax, then cast in brass.

Photo: Courtesy of Alicia Goodwin

“I love this idea of the unexpected,” she says. “Especially taking one material and making it into something else.” This is why she loves Victorian mourning jewelry, which was usually made to remember someone who had died or gone to war. Victorians wove their beloved’s hair into a keepsake to look like a basket weave, fabric, metal, or other material. “I’m amazed at the uniqueness of these pieces. The fact that they’ve survived is because they were sentimental and so strange,” she says. Goodwin plans to resume a series of custom mourning pieces for close friends and family members who have lost loved ones. It’s a project she hopes to eventually debut as a body of work in an art gallery.

↑ Textures on these gold-plated brass bangles are created in part by applying paint splatters to the metal’s surface.

Photo: Joan Cuenco

True Self as Talisman

Goodwin’s greatest joy is in making work that speaks to her personal style. She only makes what she would actually wear, she says.

That dedication to her own instincts and tastes has served her well after nearly two decades in the industry. Goodwin first set out to be a fashion designer at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, but learned quickly how the industry regards Black women – at times closed-off, or at other times, even blatantly racist. While seeking internships, she was frequently told her design portfolio was too “ethnic.”

After graduating from FIT’s jewelry program, Goodwin worked across the New York jewelry industry, including a stint in Manhattan’s high-octane Diamond District before a series of jobs under costume jewelry designers, where she says she really cut her teeth in metallurgy and casting. On the side, she was always working on her own designs. “People kept stopping me in the street to ask me where I got my bangles, so eventually I just opened a shop on Etsy so I could tell them!” Hearing that people like her designs has been “the best gift,” she says.

“My work is so personal,” says Goodwin. “So when customers tell me they are really happy with something, or they see something at a Craft Council event that they just have to buy right then for a friend or family member – that’s an amazing connection as a designer, but also on a human level.”

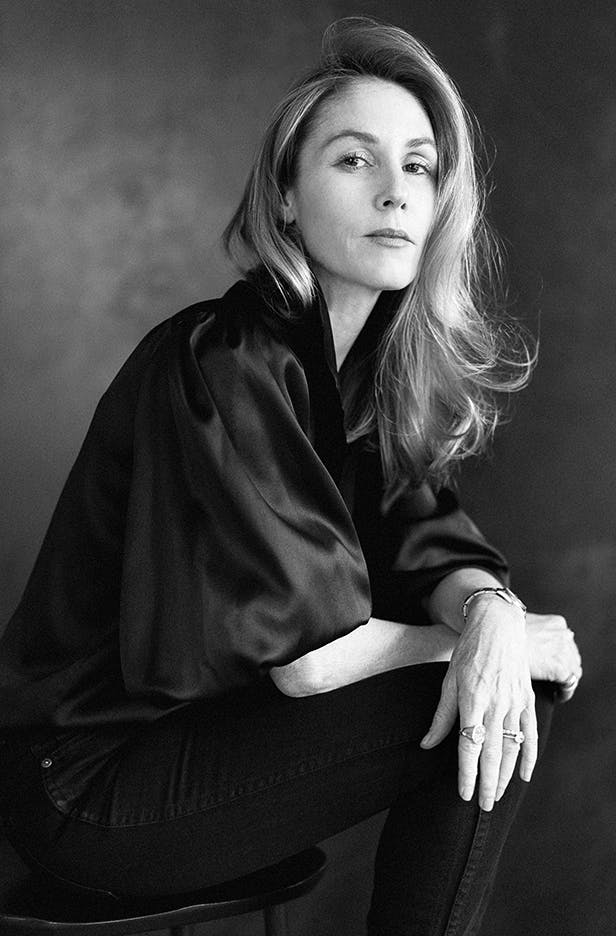

Personal connection is also at the heart of New Yorker Kim Dunham’s custom signet rings. Her designs, she explains, are wearable biographies: “Clients want to honor and remember their story. Where they are, where they came from, where they’re going.”

↑ Dunham wears a self-designed signet ring with her personal crest.

Portrait: Courtesy of Kim Dunham

The Southern-born jeweler got her start, like Goodwin, in costume jewelry design. “I always wanted to make jewelry that was meaningful,” Dunham says, and eventually, she launched a line of bridal hair jewelry that offered an inherent heirloom quality. Intrigued by the idea of modern, personal heirlooms, she says her signet rings grew out of an interest in classic, everyday pieces that would stand the test of time. Her mother had given her a signet ring as a teen, and she “was enamored with the timelessness of signet rings and their depth of personal narrative.”

Today, Dunham wears a self-designed signet with her personal crest. Her birth year is at the top of the crest, with a tiara, a compass, two seahorses, and the North Star nestled above a Latin phrase that translates to “I shine, not burn.” The tiara commemorates the beginning of her jewelry career. The compass stands for her wanderlust and love of travel, with the North Star “to remind myself I always find my way.” The seahorses symbolize her triple-Pisces star-moon-sun signs and her Kentucky roots.

↑ Kim Dunham creates modern heirloom rings that contain meaningful symbols for wearers.

Photo: Courtesy of Kim Dunham

Initially, Dunham was making rings for friends. Now, she has a sought-after, Goop-spotlighted fine jewelry business. With new clients, Dunham shares a “Proust-like” questionnaire: Who are your favorite writers and poets? Favorite quotes? Your favorite places in the world? What is your greatest fear? Then she holds a phone session to dig deeper into certain themes (like strength or love) and key symbols or images (like cheetahs or olive branches). Family and personal history are important, as well as nationality, cultural affiliations, geographic locations, and so on. It’s an intimate and sensitive process and highly collaborative.

↑ A client’s most private design choice is which words to include inside the band.

Photo: Courtesy of Kim Dunham

“I have just about every book on symbols available,” she says. Her studio’s research library contains world history, ancient cultures, art history, tarot, and astronomy, as well as astrology, psychology, and theology – anything and everything that a client’s consultation might spark. To one client who asked for a heart, Dunham suggested the leb from ancient Egypt. The water-pitcher-like shape sym-bolizes the heart for its likeness to the vital organ, but it’s more unique. It also honored the African connections they were bringing into the design.

What goes inside the ring band is one of Dunham’s favorite features. This is the most private design choice – known to the wearer and whomever they choose to reveal it to. (Dunham’s ring includes a line from Charles Bukowski: “She’s made but she’s magic. There’s no lie in her fire.”) Clients will often choose engraved messages or mantras, special dates or beloved names, or a hidden gem or birthstone. “[It’s] something that you can look to for comfort or inspiration, that’s just yours,” she says. “Keeping things to yourself is a luxury these days, a gift even,” Dunham tells her clients. “The unspoken is a talisman.”

Thoughts on this piece?

We'd love to hear from you. Send your reactions, reflections, questions, and concerns to [email protected].

We need your help to share artists' stories

As a national nonprofit, the American Craft Council relies on the support of our community to elevate artists from across the country. Please join to today to help make our work possible.