Piñata Pride

Piñata Pride

The gypsy rose is a 1964 Chevy Impala washed in a flashy pink and detailed with intricate paintings of the namesake flower. The world-famous coupe is a deeply symbolic artifact of Chicanx culture in East Los Angeles and a beautiful example of how Mexican Americans pioneered the swaggering art of the lowrider as an emblem of pride. Three versions of the vehicle were made, each picking up where the previous one left off.

But there’s also a fourth variation: a life-size piñata-style replica by Las Vegas artist Justin Favela, whose sculptures and installations of lowriders, tamales, burros, and Mexican murals are a vibrant, loving interrogation of Latinx culture’s past, present, and future.

Growing up, Favela, 31, didn’t think he would be an artist – an occupation he says “financially didn’t seem to make sense,” particularly in Vegas, where most people work in hospitality. But a drawing class at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, sparked his imagination, inspiring him to major in art – partly because “those were the only classes I was going to,” he admits with a laugh. That creative impulse has blossomed into a full-time career that takes Favela across the country: from Denver, where he exhibited one of his lowriders at the Museo de Las Americas last spring, to New York, where he will be installing a site-specific work at Harlem’s Sugar Hill Children’s Museum, to open in October.

The gregarious artist of Mexican and Guatemalan descent is deeply invested in expanding the visibility of Latinx history and culture. As “FavyFav,” he co-hosts the delightfully funny podcast Latinos Who Lunch with curator and art historian Emmanuel Ortega, a show that meanders from conversations about food to thoughtful examinations of identity and politics. Although Favela is now fully at ease with himself and his exploration of these themes in his art, he was initially hesitant to make work about his heritage and experience as a queer, brown, first-generation American. “People of color, we’re not allowed the same opportunities as everybody else,” he says, “so once you’re an artist making work about your identity or about your trauma – ’cause white people love that – there’s no turning back. I didn’t want to be pigeonholed.”

Yet it wasn’t until he decided to “f--- these hierarchies” and center his work on his own experiences, rather than hiding them from the art world’s overwhelmingly white gatekeepers, that he found his voice. While still in college, he jumped head-first into the art form that most highlights his identity “as a Latino in the Southwest, born in the United States, who identifies as an American: the piñata.”

To create his surprisingly realistic work, Favela painstakingly glues strips of tissue paper on bases built of materials such as insulation, cardboard, and Styrofoam. He loves that the piñata is an everyday object that doesn’t intimidate people, allowing him to challenge and interact with a wide audience. “If people are paying attention, there’s always a message behind the work that is not candy-coated,” he says. The format forces the viewer to question common assumptions and dominant cultural narratives, while also winking at their absurdity.

For 2016’s Piñata Motel installation, he covered the front of an abandoned Vegas motel in hot pink tissue paper, with teal trim. “People see Las Vegas [as] Sin City – or this transient town built on façade. A lot of my work is about façade as the object,” he says. The piece is also about POC visibility in Vegas. “So many people of color built this town. So many immigrants from all over the world came to this city to build and maintain this city, and nobody cares, nobody talks about it.”

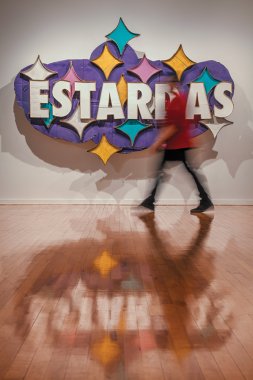

Favela’s efforts to correct the record are at once heartbreaking, celebratory, and humorous. Estardas (2010) is a cardboard replica of the old sign for the Stardust, the famous midcentury hotel demolished in 2007; but he replaced the English word with the Spanglish name – a phonetic transliteration – his grandmother used for it. “It’s a little nod to all the people who worked there. That’s the Stardust they knew – Estardas.”

His work’s complexity is particularly evident in pieces that recontextualize Mexican icons, such as the logo of murdered singer Selena or the garden of Frida Kahlo, reflecting on how they are distorted through pop culture. “It’s like an investigation,” he says, laughing. “Once I started making work about Selena, I wondered, ‘Am I making work about Selena, or am I making work about Selena, the movie?’ Everything I know about Selena I know from that damn movie. And let me do something about the idea of Frida and how she’s represented in popular culture. I’ve made work based on the movie Frida, not actually Frida.”

Refracted through Favela’s work, these symbols examine Latinx identity in the United States, particularly the many contributions to American culture by Latinx people, even as they may be excluded or viewed as secondary players in their own stories.

“You have to navigate through these worlds,” he says. “A lot of times I’m called a ‘community artist’ by institutions. What does that mean? What is the dog whistle there? I mean, it’s all art. If I was a white artist and I wrote about my art differently, would my work be called ‘social practice’? Or a happening, or performance art? I don’t know.”

Whatever it’s called, his work continues to write his people into contemporary art history, developing concepts and symbols that are instantly recognizable to Latinxes and displaying them in major art museums and galleries. “My mission,” he says, “is visibility. Turning the idea on its head of what you expect from a Latino artist. And asking, ‘How many ways can I use a piñata as a medium?’ ”