Planning Your Legacy

Planning Your Legacy

Ceramist William J. O’Brien was preparing to teach his regular class at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago when he came across a box of tools that someone had dropped off at the office. After some investigation, he was shocked to learn the package contained items that were used and owned by trailblazing modernist sculptor Ruth Duckworth, who died in 2009.

“It had all of her tools, and they were going to give them out to all the students,” O’Brien says. It was a generous impulse, he recalls thinking, but they should really be in a museum.

The experience was life-changing for O’Brien, who addresses the elephant in the studio: If artists don’t think about what happens to their work and their gear after they die, it all could be lost to the sands of time. “What happens to your studio and tools when you die is something that, unless you’re very wealthy, no one thinks about,” he says.

O’Brien kept one of Duckworth’s tools and framed it; it hangs in his studio, offering inspiration. And the Chicago artist began to think more about his own legacy. He has almost 100 pieces in storage, he’s already been through a ruinous studio fire, and his father died a year ago, leaving the family to struggle with memories and memorials. Now is the time, he decided this winter, to deal with his stored work, to review documentation for every item, and to explore where it might belong for posterity, while he has the wherewithal and mental acuity for the task.

O’Brien, 42, is not alone. Artists, their agents, and their families are looking to foundations for help and to other organizations for ideas. Many are culling storage units, downsizing studios, and considering donations to museums – or, in O’Brien’s case, mapping out donations to hospital networks.

“These questions are really tricky,” says O’Brien. “To have to acknowledge your mortality is kind of against what the whole art thing is about. . . . I have also been working on documenting my own works, plus documenting works that I’ve personally collected, all into one database.”

Preserving your legacy needn’t be overwhelming, depressing, or difficult, say the experts, who neatly boil down the process into three parts.

First, document what you have, whether in an elaborate database, an edited catalogue, or in simple cell-phone-camera images paired with a spreadsheet. Second, decide what you would like to do with your objects; research how to donate them, create a foundation, or ask your sister if she wants to administer an estate. Third, set a date to begin handling this business – talk to your accountant or an estate planner, ask museums or universities for their rules on donations, and figure out how much money will be needed to maintain the items. Alternatively, consider selling your objects and map out a timeline to do that.

“Starting with your first works, keep good digital records backed up with paper files,” says Leslie Ferrin of Ferrin Contemporary gallery in Massachusetts, who helps artists and collectors manage their archives. “It is important to document the work itself, the ideas and processes behind it. For the image, it is important to note the photographer and any rights involved, and to keep track of provenance information, such as the studio it was made in, as well as publications, exhibitions, where the work was sold, by and to whom, and, later, the same, if sold again.”

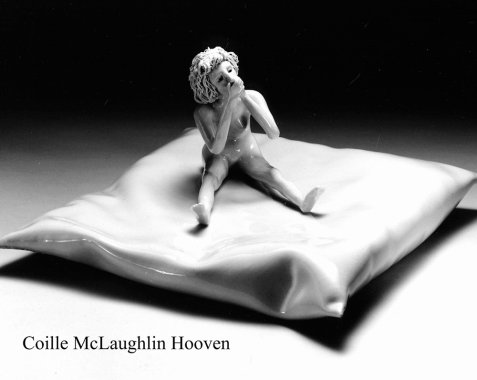

Ferrin speaks fondly of sculptor Coille Hooven, who worked with archivist Farrol Mertes on her legacy. She developed a catalogue and hired art historian Jenni Sorkin to write the opening essay. Hooven shared her catalogue with various curators, and Shannon Stratton at the Museum of Arts and Design invited her to do a solo show. “She put her focus on building her legacy, and she got this incredible exhibition and opportunity to review her life in New York at the museum she wanted to have it in,” says Ferrin. “Coille was very conscientious about her legacy and spent about five years working on that.”

A handful of companies and foundations can help artists get started. Art Legacy Planning in New York City opened this past fall and is already fielding two or three calls a week from artists, heirs, and lawyers who want to set up estates or find new homes for artwork or studio tools.

“The turning point was actually a friend of mine who died two years ago and left a mess,” says art critic Saul Ostrow, now one of four advisors at ALP. “They were ready to throw everything into a dumpster, because if her heirs inherited the work, they would have ended up being stuck with $145,000 to a quarter-of-a-million tax bill. [The artist] didn’t know what to do with it, and the person who inherits her estate knows even less. Yet everybody feels obliged to preserve it.”

Many artists put off planning, says Joan Jeffri, who runs Art Cart: Saving the Legacy, also in New York City. But it’s important to start, she says; her most recent statistics show that 90 percent of visual artists die with no will and no estate plan. “At a certain point they become terrified their work will end up in a dumpster,” she notes. “And if they don’t make a plan, it might.”

Artists at every level of accomplishment have work to do, says Pauline Shaver, executive director of the Artists’ Legacy Foundation in Oakland, California, which has been entrusted with the estate of Viola Frey in perpetuity. A good starting point might be talking to heirs about their expectations and realities, she says.

“We have been in talks with artists who have heirs with very demanding careers of their own, and the work of stewardship is not a job they can take on,” says Shaver, whose foundation is working on a process for accepting new artists into the program. “We encourage interested artists to talk often with all the stakeholders in their life and career regarding their legacy goals.”

Some heirs think that donating to a museum or university will save the day. But Ferrin and others say that’s not so easy. There are negotiations to work through, rules to follow, upkeep costs to provide, and politics to navigate.

This sobering side of the art business is something O’Brien sometimes discusses with his students. “I didn’t grow up with money,” he says. “I’m a self-made artist. In the last few months, because the economy is weird, I’ve had to ask questions I don’t like to ask. I’d like to have a plan and hopefully donate to some institutions if they’re receptive. We’ll see what happens.”

Where to go for help

Whether you’re a nationally known sculptor, a locally famous glassblower, or just related to an artist, now is a good time to begin planning what comes next. It can seem overwhelming, but these organizations can help.

Art Cart: This New York group helps older artists with direct, hands-on support and guidance to manage and preserve their life’s work, while providing students with an intergenerational educational experience and mentorship in the preservation of artistic legacy.

Art Legacy Planning: This New York-based agency has four partners who can help you identify your needs and then figure out possible next steps. With an art historian, a curator, a financial planner, and an art critic on staff, they can start you on your way.

Artists’ Legacy Foundation: This Bay Area foundation works with well-established artists who have a major legacy. They also have educational programs on estate planning and other legacy topics.

Ferrin Contemporary: The Massachusetts group offers a full range of services and expertise to artists, collectors, and estates seeking to manage their collections, offer works for sale, or make gifts to institutions. Experienced professionals can help photograph, catalogue, organize, and protect collections.

CERF+: This organization, based in Vermont, offers a free booklet, Crafting Your Legacy, designed as a supplement to other guides on estate and legacy planning or to help start the process. The publication includes eight case studies, checklists, and resources to help studio artists plan for the fate of their tools, equipment, materials, library, archives, and other artmaking assets as part of their creative legacy; also available as a free downloadable PDF.

Kohler Foundation: This organization based in Wisconsin has a long history working with artists – better- and lesser-known – to preserve large collections of work, especially outdoor work. For researching possibilities and ideas for legacy creation, this foundation’s website is worth a long look.

The Marks Project: This is a self-documentation tool for ceramic artists and their heirs. Artists have their own pages on the project website, which can link to their personal websites, making the artist’s work part of accessible records. Artists can update their pages with images of new work and maker’s marks, as well as information such as honors, studio locations, and job history.

Photographing your work: An important first step is documenting your work. Organizations such as the Racine Art Museum in Wisconsin offer affordable studio rentals with professional-grade cameras to help. The museum is also a good resource for finding similar services for artists in your area.

Poba: This online hub seeks to preserve the legacy of artists who have died without full recognition of their gifts to the world. Poba offers help to heirs and estate executors as well.