Raised Ink

Raised Ink

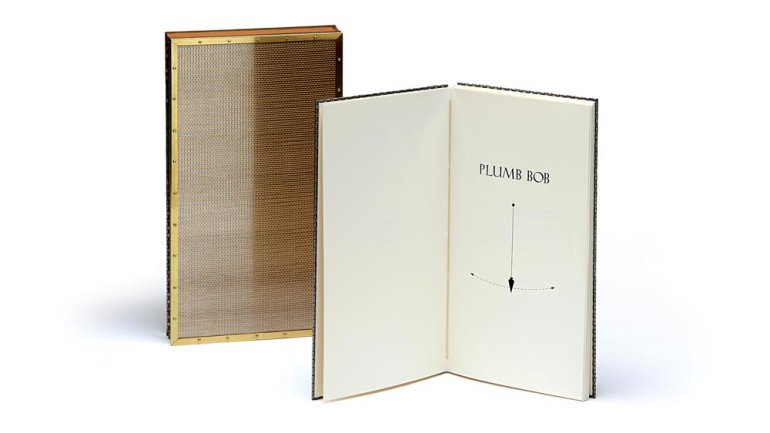

Fine & Dirty: Contemporary Letterpress Art

“Today the fine press book is thriving.”

These words, painted on the wall, greeted visitors to “Fine & Dirty: Contemporary Letterpress Art,” a touring exhibition of 50-some books, dioramas, and a smattering of other print media, at the Minnesota Center for Book Arts. How does this special kind of book manage to prosper, even in the digital era? As the wall text continues, it suggests the artist-made book is imbued with the same sensory qualities as a handmade necklace or pot – because the fine press book derives not from literature but from “the properties and pleasures of craft.”

This statement from co-curators Betty Bright and Jeff Rathermel invites constant comparisons, perhaps inadvertently. With each object in the exhibition, you can’t help but wonder: Is it closer to a book – perhaps a new, more adaptive breed to propagate the print species? Or is it more like craft – with its hand-stitched Japanese bindings and fabric inlays?

The answer is obvious in some cases, as with Light Blue Sun Hat (2010) by Diane Jacobs, a wide-brimmed headpiece woven entirely from delicate strips of paper with phrases like “business girl” and “fallen woman” printed on letterpress.

The exhibition also includes some cheeky postcard swaps from Ladies of Letterpress, a membership organization for international printmakers; there are also a couple of brochure-like pieces with die-cuts and accordion folds. But the show’s most compelling objects (and the overwhelming majority) are unmistakable in their pedigree: They take after hardcovers. Sometimes they dance between language and design. Ken Campbell’s book Dominion (2002) features layered phrases in letterpress, which renders them unreadable. Didier Mutel’s take on The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1994) has disorderly typography and disorientingly varied font sizes.

There’s even reverence for classic, if often overlooked, genres of books. Inge Bruggeman’s Unable to Find Each Other, Let Alone Ourselves (2007) isn’t the only riff on the illustrated characters from vintage medical texts. Likewise, Gaylord Schanilec’s Sylvae (2008) is one of several works inspired by old-fashioned field guides. How pleasing to peruse books like these, which satisfy our appetites for both story and beauty.

With their inky imagery and marbled papers, the best selections prey rather aggressively on the desire to touch. Take Julie Chen’s True to Life (2005): It features a brilliant tablet-like interface with sliding pages attached to tiny wooden handles, and the viewer wants desperately to pull.

Michael Kuch’s Disasters of Love: A Defense of Delilah (2006) is equally enticing. This collection of poems, intaglios, and lithographs is displayed with its colorful folding box, arranged as an easel, face-down and partly obscured. On the propped page, the eye travels immediately to the lithograph of a nude figure. After a minute or two, the text proves even more seductive, triggering an almost primal need to hold the narrative in your hands.

Alas, Kuch’s gorgeous book, like all the others, is hands-off. Everything here is encased in glass, with only single spreads exposed. Even when you stoop, crouch or stretch your neck, you can never fully grasp the slivers of treasure you see (just barely) in this roomful of fanned pages. The show satisfies certain visual cravings; that it leaves you with such longing testifies to the tactile appeals of letterpress and other fine press techniques.

An e-book can’t do that. No wonder these books are thriving.

Christy DeSmith is a Minneapolis-based freelance writer. She covers arts, culture, and travel.

Minnesota Center for Book Arts

Minneapolis, Minnesota

July 8 – October 16, 2011

The Center for Book Arts

New York, New York

January 18 – March 31