Revealed

Revealed

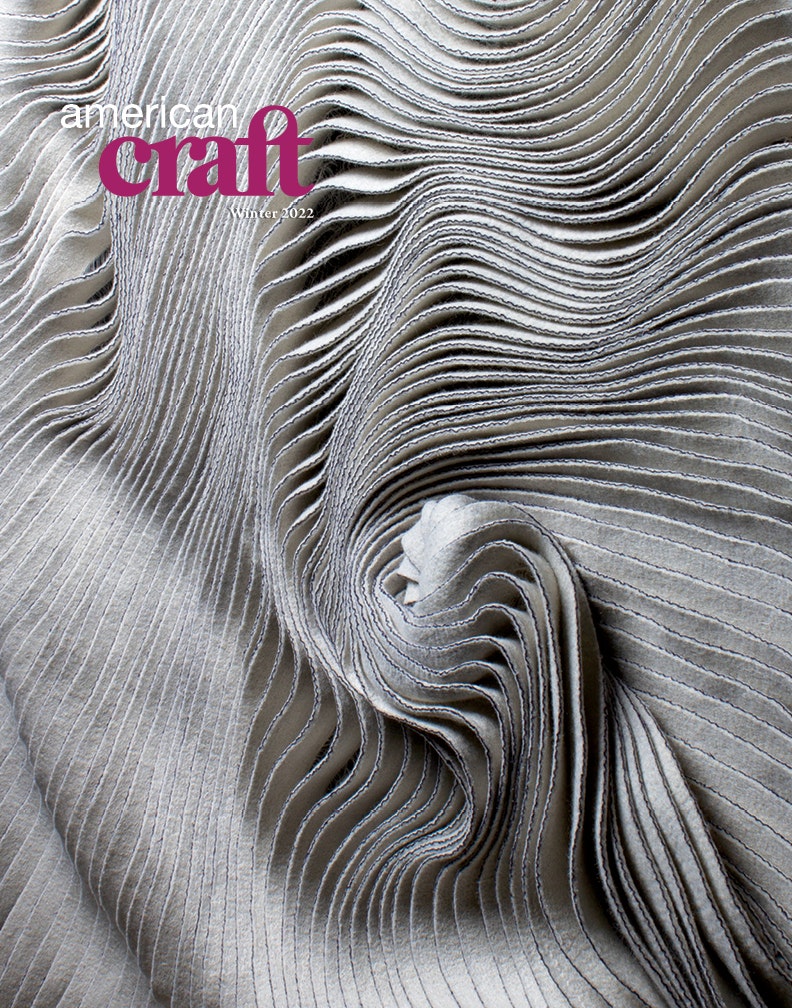

To make the Fauteuil Club Chair, Pillow Top Ottoman, and Stitched Stool, Matthew Nafranowicz uses upholstery techniques that predate the introduction of foam in the mid-20th century. Stitching that’s usually kept hidden is here revealed. Photo by Chris Hynes.

One look at their Nordic Wing Chair gives a sense of their work: beautiful and deconstructed; fine, not fussy. We see a chair stripped to essential design elements, using as few pieces of cherry as possible—a mere frame, really. But the exposed traditional padding, the crosshatched burlap, and the not-quite-straight paths of hammered blued steel tacks tell us we’ve found something . . . different. And different is good. Good and durable.

The Nordic Wing Chair features exposed traditional padding and stitching and a seasonal slipcover for the winter months. Photo by Todd Maughan.

Based in Madison, Wisconsin, Nafranowicz discovered the tradition of fine upholstery after graduating from college when he took a job in an upholstery shop to make ends meet. Over two winters—in summers he did ornithological fieldwork—he acquired an understanding of the work, craft, and business of upholstery. Later, in Wyoming, he took a similar job in the only upholstery shop in Jackson. As he began to ask himself where he could go to learn more, two threads in his life joined.

While Nafranowicz gained skill and confidence with upholstery, his girlfriend Susan (now his wife) was studying toward her PhD in French history. Her studies would take the couple first to New York City and then to Paris.

In the summer of 2000, at age 24, Nafranowicz began working with Jean-Charles de Moriniere and his firm, Trade France, in New York to learn something of high-end upholstery work for interior designers. His attention was caught by the carefully constructed, fully upholstered furniture used by Moriniere for his custom interiors, built in an on-site workshop. The quality of the craft, especially the hand-stitched upholstery, surpassed what Nafranowicz had seen previously. For six months he attached himself to the workshop, whetting his appetite for deeper expertise.

“Every tack, every stitch serves a purpose.”

—Matthew Nafranowicz

TOP: Nafranowicz adds lashings to the platform to hold the coir fiber in place. MIDDLE: An ottoman frame with coir ready for burlap. BOTTOM: Burlap is stretched and tacked to the frame. Photos by Emily Julka.

After a year in New York, the couple moved to Paris. There, Nafranowicz began his apprenticeship at Atelier Tapissier Seigneur. The Atelier, according to its website, refers to its employees as “Upholsterers and Decorators who uphold ancestral craftsmanship.” Through his training there and a class he elected to take at La Bonne Graine, a school for furniture making and upholstery, Nafranowicz at last came to understand the venerable history of modern French upholstering. For a year, he immersed himself in the demanding handwork required for excellence.

Humble and soft-spoken, Nafranowicz admits that his practice, though it has matured over 19 years, reflects less initial training than that of his French peers. Nevertheless, his method embodies devotion to a centuries-old métier. “My work,” he says, “reimagines eighteenth-century techniques in a modern American context.”

Gathering Threads

In the States, the majority of modern upholstery work is a matter of manipulating foam and fabric. While foam may vary in consistency and density, managing it relies on cutting, placing, and securing. Foam itself is not difficult to find—any DIYer can track down affordable foam for a repair—but it may require some resourcefulness to find and manipulate the fabrics that cover the foam. The art of this work is found in the care taken with sewing.

In traditional upholstery, however, the materials themselves lured Nafranowicz, who loves working with them, starting with the underlying layers of burlap. The jute burlap used in French upholstery has an open weave and takes shapes well, such as rounded corners or curves. Tight and strong, expensive linen burlap may be used, in Sweden especially, or the middle-grade Hessian burlap, a weave between the French and Swedish, often used in British upholstering.

ABOVE: Portrait of Matthew Nafranowicz. Photo by Emily Julka. RIGHT: Swedish author and illustrator Maj Lindman’s children’s book Snipp, Snapp, Snurr and the Big Surprise (1937) inspired the simple shape of this walnut Nordic Wing Chair. Photo by Chris Hynes.

“I want to push the traditional techniques ahead, showing respect for centuries of the craft without relying on nostalgia.”

—Matthew Nafranowicz

And there are the fillers, the horsehair and coir, the latter derived from coconut husks. Horsehair, soft, pricey, and extremely durable, may be reused after decades, if not centuries. When he repairs an antique chair—a great-grandmother’s favorite, for example—Nafranowicz may be able to reuse the original hair. “I’m always amazed how horsehair may be reduced in volume by almost two-thirds while manipulating it into the form,” he notes.

A first fill of coir; perhaps a second fill with hair, using the regulator, an awl-like tool, to stuff and distribute the curly substances; measuring, cutting, stitching a siege; tacking, layering, sewing the corners; binding the work with heavy needle and heavy thread—this is the close work of three or four dozen hours for a single piece.

Traditional Meets Modern

In upholstering work, the “straight thread”—le droit fil in French—found in the weave of burlap locates the centerline that runs, say, front to back on a chair seat, dividing it in half. It orients the upholsterer to the work.

In this Plains Chair, the leather back and leg wraps are sewn by hand through the wood frame. Photo by Todd Maughan.

In late 2002, Nafranowicz founded the Straight Thread upholstery shop in Madison. While he hoped to find enough upholstering work with period furniture and interior designers to use the skills he had acquired in France, by 2003 he had repositioned his company to share the busy local market for more common furniture repair and reupholstering. His bread and butter, then, relied on skills first learned in Madison and Jackson years earlier and perfected over time in New York and France.

In 2013, after 10 years in business, Nafranowicz designed a footstool with an upholstered leather seat that revealed the hidden shape and stitching of the upholstery. “I wanted to push back a little against the tradition,” he says, regarding his first foray into a more “demystified” line of furniture. “But I also wanted to bring attention to the skill and care in a craft generally concealed.” Over the next three years, he followed this experiment with a bench and three chairs. The Fauteuil Club Chair, his most recent and demanding addition, appeared in 2019. For each piece, he and his partner, Zach McDole, strip down the frame of the furniture to basic design elements. The simplicity of each piece highlights the handcrafted upholstery. The viewer may appreciate the oiled cherry or oak, but it’s the burlap, the stitching, the tacks, all of it holding in carded horsehair or coir, that earns admiration.

Nafranowicz developed a technique for stitching leather directly onto the pad, shown here in this Stitched Stool. Photo by Chris Hynes.

No single element in the pieces produced by the Straight Thread Chair Company—a younger sibling to the Straight Thread—may be seen as purely decorative. “Every tack, every stitch serves a purpose,” Nafranowicz stresses. Even so, the stitching bears the idiosyncrasy of the maker, reflecting the hand that has performed the work. “I want to push the traditional techniques ahead,” he says, “showing respect for centuries of the craft without relying on nostalgia.”

Nafranowicz acknowledges the decision to show the work of a craft kept secret may challenge traditionalists. Even so, a recent invitation to present at Malmstens Linköping University in Stockholm, Sweden, a center for furniture craftsmanship and upholstery, and initiatives in England and the US suggest Nafranowicz offers innovation that designers and artisans—customers, too—find both subtle and bold, respectful and playful. It’s this serious play that follows a straight thread through the future of tradition.

thestraightthread.com | @straightthreadchairco

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.