Reviving Utopia

Reviving Utopia

Graphic designer and product developer Judy Smilow has a lifelong connection with modern furnishings and art. The daughter of midcentury designer Mel Smilow, she grew up surrounded by her father’s paintings, lighting, and furniture in Usonia, a New York cooperative community of 40-plus homes designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and his followers.

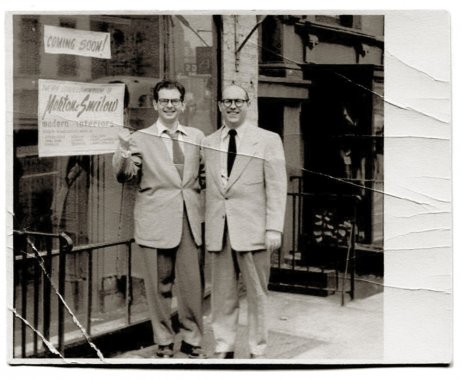

Smilow moved to Manhattan in the early 1980s, where she designed for several firms and the Museum of Modern Art. In recent years, she has returned to her familial roots: furniture. In 2013, about a decade after her father’s death, she reintroduced two of his collections, alongside her own glassware, under the moniker Smilow Design. Last year, she followed up the brand’s successful launch with some of her father’s nature-inspired lamps and pendant lights.

The business is a family affair. She and husband Steven Schoenfelder, a fine art book designer, create the print materials, and their children – Maia, a social media strategist, and Aaron, a graphic designer – help with marketing.

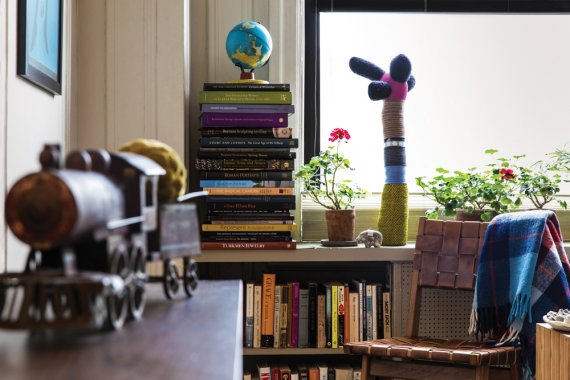

Today, Smilow lives with her husband among her father’s furniture and artwork in an Upper West Side two-bedroom apartment. The couple’s eclectic, often playful, belongings reflect a lineage of artists – Smilow’s glassware, paintings by family members, books designed by Schoenfelder, and other pieces.

How did growing up in a modern house in a Frank Lloyd Wright community influence you?

Modernism was not just a design style; it was a way of living, embracing a more casual lifestyle. Our community was connected in so many ways and was a success from every angle. It was a magical place to grow up. Families had a similar state of mind: political, similar ages, mostly Jewish. We were called “the pinkos on the hill” [for left-leaning politics]. The other part, for me, as a designer, is that I grew up in a house that was like a mini-museum, with my father’s furniture and art. My sister [painter Pam Smilow] and I got our strong sense of proportion and composition from him. The nature aspect was also very impactful. Every room had a giant window and doors to the outside.

Since you left Usonia, you’ve lived in New York City, a very different environment.

I love being here, but for me it wasn’t a necessity. But my husband is from Minnesota, and he really wanted to be in the city. Plus, we wanted to have a certain lifestyle raising our kids.

We moved to our apartment, on the sixth floor of a 16-story pre-war building, in 1991, when we had our daughter. It’s got a living room, small dining area, and nice-sized kitchen. By other people’s standards it’s unusual to be in a small place with children, but not in New York. Now, with the children gone, we have a great rent-stabilized apartment that’s maybe too big for us. We do have many windows that bring in light, and we’re between Riverside Park and Central Park. I don’t think I’d be able to live in the city if I didn’t have that nature.

You graduated from Parsons School of Design with a BFA in communication design and have held positions in product design and development, but you also have a glass line that you launched in 1986. How did that start?

I grew up doing crafts during the Whole Earth Catalog period [in the late 1960s and early ’70s]. We were all weaving, doing batik, tie-dye. I made leather belts and wristbands. [In my mid-20s,] I took classes in jewelry and then got interested in glass. An experimental studio had a sandblaster that you could put quarters in to use. I cut out patterns on glass plates and ended up getting them manufactured. The Dots and Dashes plate sets ended up in the Cooper Hewitt permanent collection. That was a very cool thing.

How did you come to reintroduce your father’s work?

My father saved the archives. Looking at them, I thought how the designs are still relevant, so the idea came to try to license them. I talked to a lot of big players, but then the economy fell apart. Finally, in 2012, I had the chance to have a chair made. I found a factory in Pennsylvania to make it, and that’s the one we still use today. The next year I had a chance to join ReGeneration at ICFF [International Contemporary Furniture Fair] to launch the line with 10 pieces. We recently introduced the lighting and plan to give it a big launch at ICFF.

What kind of changes did you make to the work, if any?

The biggest was to look at my father’s many designs and put them into collections. That required some tweaking to make things consistent. But I still used his original designs, and I think of his sense of proportion as brilliant. The lighting was very challenging to come to market. The shades are made with strips of hand-colored birch dowels over vellum – which makes a beautiful light – and all the dowels have to be glued by hand. For both furniture and lighting, there are more varieties of materials and color.

The other big thing is my father believed that working people should be able to afford modern design. But you can’t make furniture in this country [today] at the price point he did. So I had to rejigger the business as a luxury line. We’re thinking about maybe selling vintage, prototypes, and slightly used [wares], as we feel compelled to try to service that market.

Speaking of the vintage market, I see a lot of original Mel Smilow furniture online, at pretty high price points.

I think it’s the result of the work being brought back; now it’s recognizable. For many years, nobody knew who Mel Smilow was. My father really slipped through the cracks, mostly because he never signed his furniture. But that’s all changed. I continuously answer emails about his work.

Was it difficult to see the Usonia house sold in 2000?

It was. My father had Alzheimer’s and ended up in a nursing home, and [the house] was too much for my mother to manage. The people who first bought it made a lot of changes, but then it was resold [about a decade later] to the architect Henry Myerberg, who restored the house to its original condition. That was so great. He actually connected us to ReGeneration. My sister and I took some of the furniture. So my apartment has a mix of old and new pieces – a bed, dressers, side chairs, a credenza, a lamp.

What are some of the other collectibles in your home?

My husband and I are both very visual and love artwork. We collect toy trucks and cars. I had a Matchbox car collection when I was young, and my father and uncle raced MGs. We also have a small collection of globes. Artwork from the family is the most meaningful.

Other than that, we have a little fabric tree by Elodie Blanchard, a Maira Kalman print, and an Ellsworth Kelly print in the kitchen that was given to Steve. In our bedroom are photos by Hiro of our children’s feet when they were 4 months old with chubby legs.

Not only do you have loyal original customers, you’ve brought in new ones. How does this connection of past and present feel?

My father had such a devoted customer base – it’s just amazing. They reach out and tell their stories about going to the showroom or meeting him. These blasts from his past are very special. Overall, making the furniture has felt like being with my dad again. It’s been a total thrill to have him in my life.