Ruin and Redemption

Ruin and Redemption

Nava Lubelski will never forget the moment someone spilled a glass of red wine all over the fancy dinner table.

It happened in 2007 at a gala hosted by the Cue Art Foundation in New York, where Lubelski had a residency. A clink of glass, a collective gasp of horror, people scurrying to clean up the mess – she watched the little drama play out and got inspired. The next morning, when the caterer’s truck came to pick up the rented party linens, she was waiting.

“I ran over to the guy as he was packing things up and said, ‘You have a yellow tablecloth in there that’s ruined; somebody spilled wine on it. I was wondering if I could have it,’ ” Lubelski recalls. He was puzzled but gave it to her. Back in her studio, she captured and commemorated the jarring incident with some red stitchery around the splotch and drips, elevating a splash of wine to a vivid painterly gesture. She then draped the cloth on a tableshaped pedestal, styling it as a sculpture, and titled it Clumsy. When the piece ended up in “Pricked: Extreme Embroidery,” a popular 2008 exhibition at the Museum of Arts and Design, the New York Times singled it out as a highlight of the show.

At first sight, Clumsy makes us wince, reminding us of some awful instance where we lost control and made a mess, “ruined” something – a tablecloth, a friendship, ourselves. Then we take in Lubelski’s artistry and humor, and smile: Maybe it all worked out anyhow, and we’re better for it. In all of her art – from embroidered textiles to paper sculptures to conceptual installations – Lubelski tells stories of damage, repair, and reinvention, and celebrates the defiant beauty of imperfection.

“My goal is to make each piece an epic. Love, lust, tragedy, happiness! Horrible disfiguring accidents and beautiful redemption, all of it,” she says with a laugh. “I want it to be deep and dark and hilarious, all at the same time.”

Once, on a walk, Lubelski watched a boy run along the sidewalk, drawing chalk circles around puddles. “He’d draw around a pile of brownish nastiness. Then he’d go a few steps further, where there were trickles, and he’d circle each little bit,” she remembers. “I was mesmerized. It made me think that maybe there is a human instinct to contain, outline, highlight, and glorify something gruesome.”

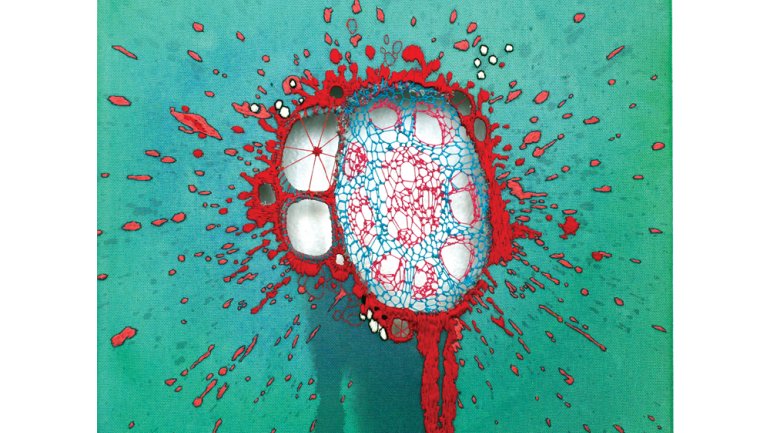

That she uses the traditional and genteel craft of needlework to depict unsettling images (some of her abstract shapes suggests wounds or cancer cells) makes her work all the more disruptive. A piece may start out as an old blanket or other found object already sullied by age and wear; or she’ll stretch a canvas and deliberately slash it, poke holes, splatter paint. Then come the stitches, which can be highly delicate and uniform – little lace windows, bits of doily, lines so finely rendered that they look like ink drawings – or raw, loose, and gnarled, depending on how she improvises. “I create chaos,” she says of her process, “then bring my needle and thread to resolve it.”

Lubelski’s grandparents were tailors, so needlework is probably in her blood. Making things with thread and fabric always came naturally to her, though for a long time she didn’t consider it art: “I thought art was big, serious, abstract paintings.” The daughter of an abstract-painter father, she knew that world, having grown up in a loft in New York’s Soho arts district in the 1970s. Creativity was strongly encouraged in the family, and as a kid she would roam the neighborhood with her pals, dumpster-diving for scraps of fabric, pipe cleaners, and other odds and ends to play with. “It was an adventure. We felt like we could have whatever we wanted and make whatever we wanted out of it.”

Instead of art, however, she chose to study Russian language, literature, and history at Wesleyan University (“I had taken Russian in high school and just loved it”), spending her junior year in Moscow. After graduating in 1990, she moved to the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, drawn to its emerging reputation as a new bohemia. (It did not disappoint, she says, fondly recalling wild art parties featuring absinthe, giant shadow puppets, and experiential themes.) She was making art then, but with no real direction, “just finding things on the street and taking them home and painting all over them.” By day, she helped build backdrops and props for music videos starring bands such as the Roots, Def Leppard, and Hole. That job became her art school, she says, challenging her to work with a team of makers to create whatever effect was needed – “a giant tunnel that looked out through a window, all these crazy things. We would figure out how to do it.” After a shoot, they would break down the sets and dispose of the components, usually by sneaking them into other people’s trash bins around the city.

“One night, we found this great dumpster on a dark street. It was full of amazing, big pieces of fabric, maybe from a factory that went out of business,” recalls Lubelski, who must have felt like a kid again. “I took home boxes of it and started playing, sewing, making collages. It felt so fresh. I began to see pieces of fabric as fields of color, and threads as drawn or painted lines. Or I could fill whole areas with stitching. I got excited about the possibilities of how painterly I could be with thread.” This was around 1998, and it became the genesis of the work she continues to this day.

In 2006, looking for a change of scene, Lubelski and her partner moved to Asheville, North Carolina. (He’s a musician and clinical social worker, and they now have a little boy.) Since then she has maintained her New York connection through various residencies and shows, while exploring her signature themes in new forms and scales. An experiment with machine-made editions of her stitched canvases produced at the A-B Emblem embroidery factory in Weaverville, just north of Asheville, led to her discovery of a trove of discarded scraps of flawed fabric – “non-conforming goods,” they’re called – which she used to create large installations.

For Lubelski, each piece is a collaboration, if only unconventionally and after the fact. With Clumsy, her team included the party planner who chose yellow for the color scheme, the guest who spilled the wine, the people who blotted it, the man who gave her the tablecloth. Her factory-produced editions involved the machines that interpreted her designs (often wrongly, to her delight) and the technicians who strived for quality control (even as she reassured them she wasn’t looking for a perfect outcome).

Her most poignant collaborations, perhaps, are the small sculptures, resembling relief maps, that she builds out of hundreds of tiny hand-rolled scrolls of cut paper, her version of the Victorian art of quilling. The earliest ones were made from her own old shredded tax forms and rejection letters from galleries and grantmakers. Soon people started bringing her papers to turn into art. A curator friend handed over a bundle of World War I-era love letters he’d rescued from a roadside bin. Another woman contributed her decades-old art school portfolio. Seeking closure and catharsis, a heartbroken man gave her a box of cards, printed emails, and paper souvenirs, all pertaining to his first love, a relationship that had marked his coming out as gay. Much more than recycling, Lubelski says, the sculptures are “a way to take all of this paper that is embedded with so much data, meaning, and emotion, but no longer serving a purpose, and reinvent it.”

In an era when TV shows seek to rehabilitate hoarders and best-selling books tout the wonders of decluttering, Lubelski’s tender embrace of the imperfect and unwanted may not be on trend, but it is the heart and soul of her art. “I’m constantly ridding myself of things that don’t bring me joy, by transforming them into things that do,” she says. “I believe in transformation. That’s a more beautiful world to me. How can we make magic with stuff that isn’t all that special?”

Joyce Lovelace is American Craft’s contributing editor.