The Scholar's Stone

The Scholar's Stone

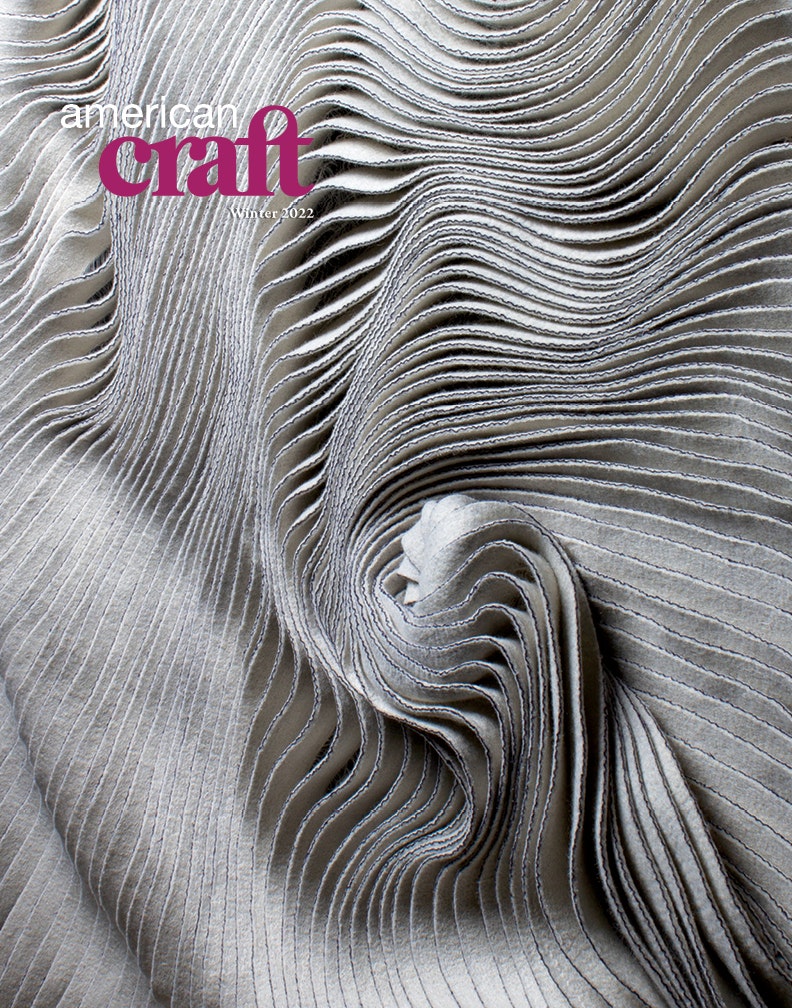

Jovencio de la Paz found this stone along the upper part of the Calapooia River in Oregon, then fashioned a stand for it out of Sculpey clay. Photo by Jovencio de la Paz.

At the Upper Calapooia, which flows from the Cascades and meets the Willamette River near Albany, Oregon, I reenact the queer, human impulse of gathering stones I admire. I carry them in my hands for a time, walking along the riverbank, seeing their shape in my mind’s eye by navigating their surfaces with my palms and fingers. It is an intimate way to engage the earth, more often than not ended moments later when I drop the rock back on the pebbled shore or toss it into the river. It’s hard to know what compels this sudden abandonment . . . Have I known the stone enough in that short time? Very few river rocks I have met complete the journey with me back to my car.

There are times, though, when a stone is utterly shocking. Maybe it is its perfect roundness, or that it looks so much like a frowny face, a potato, a penis, a Kia Soul, or some other recognizable thing. Sometimes it is a lightning thread of white crystal held in the dark mass, and sometimes it’s a particular hole, a soft and mysterious opening. Whatever the quality, something in me begs not to be parted from these stones, and they, at best, end up on my office desk at the university or above my kitchen sink at home; at worst, they become forgotten miracles rolling around in the back of my car. From one perspective, this is a sad end for them, but only if one thinks in the highly limited, human-centric sense of time. In planetary time it is laughable to think this is an end at all. They will certainly be liberated from my silly little office once I am gone, when the University of Oregon is utterly forgotten, razed to the ground and returned to dust; when my mementos and photographs, all the meaningful moments of my life, so unimportant in the magnitude of geologic time, have sunk to the bottom of an ocean yet to be created.

But their craft was not so much in the making of something . . . rather one of arriving in the world, of seeing it as clearly as one can and then showing some appreciation.

Not long ago, in ancient China and Japan, Zen poets, artists, monks, and even common folk would revere certain stones that crossed their path. These stones may have been found on a high mountaintop, in a deep forest stream, or at the bottom of a great waterfall. They struck their admirers with some sense of “awakening,” a spiritual turning toward cosmic truth, a “thusness” of things. The admirers would take the stones with them, carefully observing their contours. They would carve simple tables or platforms out of wood to cradle these stones, so they could be studied and contemplated for generations. But their craft was not so much in the making of something—altering the material world toward a pleasing or useful form—but rather one of arriving in the world, of seeing it as clearly as one can and then showing some appreciation.

The stones became known as suiseki (水石), or “scholar’s stones,” and they can be found throughout the homes and temples and meditative gardens of the Far East. Some individuals spend their entire lives honing their sensitivity to notice rocks, becoming masters at finding these unique stones out in the world.

I often forget that when I look at something, anything, I am engaging in a kind of touch. As my gaze wanders over the world, I cast a certain vote once my eyes finally come to rest.

In my distracted life, between glances at my phone and computer and the TV that has been playing in the background, I take out some rocks I’ve collected over the years and turn them, once again, over and over in my hands. I select one and, lacking the necessary woodworking skills, I smash Sculpey clay into a shape that is a poor, distant echo of the skillfully carved platforms of Japanese and Chinese masters. Later the stone sits slightly wobbly in the hardened plasticine cradle atop a shelf in my living room. I think it doesn’t mind, or maybe it doesn’t even notice, in its million- or billion-year lifespan, that I, so small and so new, one day during a pandemic, loved it enough to want to be near it.

jovenciodelapaz.org | @jovenciodelapaz

Discover More Inspiring Artists in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.