The Seeker

The Seeker

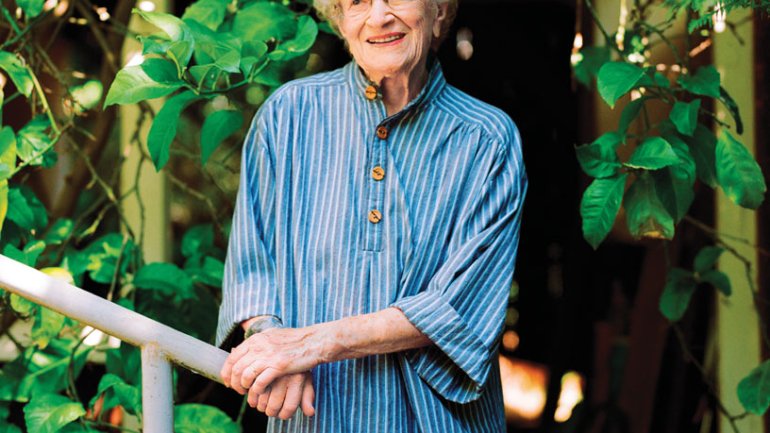

At 93, enamelist June Schwarcz lives each day on a focused artistic quest.

In the nearly 60 years that June Schwarcz has been applying enamel to metal, she has found inspiration in tribal art, olive oil cans, medieval monks’ robes, fog, the Stanford linear accelerator, worm-eaten wood, Fortuny fabrics, Moorish ceilings, sidewalks, Paul Klee, Mark Rothko, illuminated manuscripts – and her grandson’s low-slung baggy pants.

“All those things are starting points – like kicking off from a swimming pool,” says Schwarcz, running her finger over a recent work, a sparsely enameled cubist construction of voids and angles. “I’ve been chasing after beauty all my life.”

Since 1955, when a skeptical museum curator took a look at Schwarcz’s hand-hammered basse-taille pieces and proclaimed that she had restored his faith in enameling, her definition of beauty has been as fluid as molten glass, and her base material has become ever more pliable. After hand-hammering sheet metal for many years, Schwarcz embraced copper foil, which can be pleated, shaped, and stitched like fabric. Then, a few years ago, she discovered an even more ephemeral material: copper wire cloth. “Most of my new stuff is made from this,” she says, fingering a piece of the diaphanous, mesh-like fabric still on the bolt. “It’s so cool – it has the best properties of textile and metal. I can make it look light and delicate, or tough and gritty.”

Timothy Anglin Burgard, a curator at San Francisco’s de Young museum, which owns 16 of Schwarcz’s pieces, is intrigued by what the artist can do with copper wire cloth. The material is “inherently fragile before June transforms it into an extremely solid, enduring sculpture,” he says. “Before plating, the mesh is visually physical, but hardly there – on the edge of nothingness.”

At an age when many would be looking back, Schwarcz is determined to move forward – though her health is fragile and she receives home hospice care. She describes an upcoming show with photographer John Chiara, a visit from friend Kiff Slemmons, a new yellow patina that the artist Frank Connet brought by for her to try. As she leads the way down the steps to her home studio in Sausalito, California, she quickly preempts any gushing about her productivity: “You know, when you’re 93, people think you’re amazing just for getting out of bed in the morning.” Then, more seriously, “With a limited time to live, there’s a decision to make every day – what to spend it on, what to create.”

How much, after all, is there left to explore? If the artist’s fingers have grown stiffer and her body more tired, the desire to work has not ebbed. “It’s a compulsion!” Schwarcz says. “And because my process has never been entirely controllable, there’s always an element of uncertainty and surprise about how a piece will turn out. This gives me something to live for.” Inside the sanctum of her studio, there’s an archipelago of pieces in progress. An intricate paper mockup of a vessel with horizontal slashes rests on one table; the copper version is in the plating tank. On another table, a collage of mesh, foil, and wire is arrayed in preparation for a bowl inspired by Japanese boro, the patchwork fabric made from snippets of cast-off cloth. In the back, a mechanical drawing of an old ship has been partially embossed onto foil, a piece Schwarcz got stuck on 15 years ago and recently decided to finish. “Being in my studio gives me a feeling of peace I don’t have any other time.”

Upstairs, where Schwarcz has lived since 1954, the living room is filled with artifacts (including an old piece of African wood that she likens to a De Staebler sculpture) and ancient objects mingled with works by Robert Motherwell, Ellsworth Kelly, Richard Diebenkorn, Louise McGinley, Anne Hirondelle, and many others – all washed in light from the picture windows framing the Sausalito bay.

Her own recent work is arrayed on a bookcase in another room. Some vessels have the sheen and delicacy of ceramic, others seem to have grown directly from nature or to be decomposing back into it. The rich, transparent enamels are used judiciously and often reserved for the interior: a shock of citrine, a molten wash of cerulean you have to seek out.

Still the consummate experimenter, Schwarcz continues to play with and strip down her material. “As much as I love color, I also crave coldness and roughness,” she admits, referring to a handful of wire cloth pieces that have barely been transformed beyond a touch of electroplating or patina. “As you age, so do your ideas about what’s beautiful.” One cylindrical vessel, patinaed black like the salvaged remains of a fire, is torn and shredded in places, revealing its vulnerability. Another work has copper scrap and an announcement card from one of Schwarcz’s past exhibitions embedded between flattened layers of the translucent metal, suggesting a kind of memento mori.

Of course, the artist’s system of numbering rather than naming her works invites projection. As she says, “I want to make beautiful objects that reflect our experiences and emotions, and I want them to contain their own meaning. I have pieces from the Han Dynasty, and it comforts me to think we can find beauty in things 200 – or 2,000 – years after they were made. I love being part of that procession.”

Deborah Bishop is a writer and editor based in San Francisco.