Things that Go Bump

Things that Go Bump

Q: Go to a fine craft show, and you’re likely to see everything but paintings and photography. Why is it assumed that craft is three-dimensional?

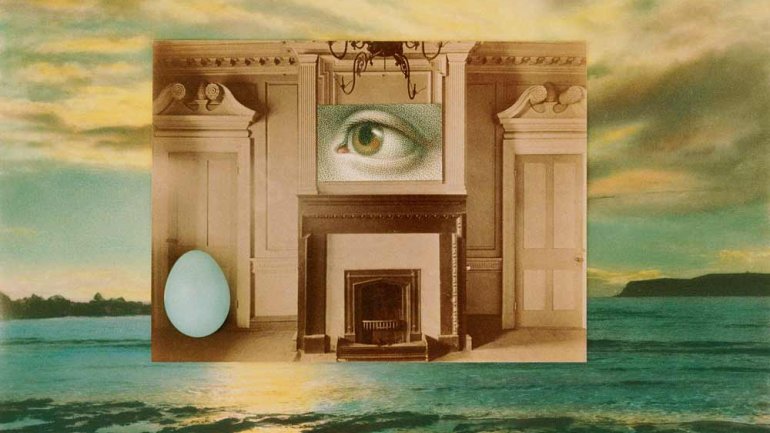

A: The painter Ad Reinhardt, asked to define the term sculpture, replied rather wonderfully: It’s “something you bump into when you back up to look at a painting.” It’s a good line, partly because it makes a joke out of the arbitrary idea that painting is the ultimate art form. But Reinhardt’s witticism also gets at an essential difference between two- and three-dimensional art. Whether it’s an oil on canvas, a watercolor, a drawing, a photograph, or even a film screen, all flat art sits within a frame of sorts. This demarcation might be literal or only implied, but either way, that edge separates the artwork from the rest of the world. Whether hung in a white-walled gallery or above a sofa, a framed painting stands apart from us. Sculpture can aspire to this condition; that’s what a plinth is for. But it’s there to bump into, along with all the other objects in our lives.

Of course, craft isn’t synonymous with sculpture. There is a long history of classification in which the two are distinguished from each other, typically on the basis of function or prestige. It’s one thing to fondle a handmade ceramic bowl and another to try to sit on the lap of Michelangelo’s Pietà when the museum guard isn’t looking. But such distinctions are ultimately about social custom, not the intrinsic nature of objects. A handcrafted chair and a handwoven shawl share with even the most rarefied sculpture a certain three-dimensional interjection into our lives and our spaces.

To take the argument further, flat and dimensional art, fine and decorative art, aren’t as different as we tend to think. It’s obvious that all sorts of craft skills are involved in the disciplines of painting, drawing, photography, and film. For some painters, in fact, the experience of making a work is profoundly artisanal, every bit as saturated with the know-how of materiality and technique as glassblowing or silversmithing. And many paintings aren’t even very flat. They are stretched over wood frames, usually made by hand in a studio.

But somehow we still expect to revere paintings from a distance and to use and abuse craft objects in the course of everyday life. Cabinetmakers must plan for collisions with the vacuum cleaner, and potters know the perils of the kitchen sink. And maybe that’s the way it should be. Given the many satisfactions that everyday life has to offer, its infinitely rich variety compared with a white-walled art gallery, the real world is a mighty interesting place.

To quote another artist, Gord Peteran, “that’s where every sculptor should want to be.” Peteran, who works within the realm of furniture, loosely defined, is an example of a contemporary maker whose objects occupy a room intelligently, responding to specific conditions of use and placement, rather than pretending that the rest of the room is not even there. Works like his, which embrace the contingent rather than ignoring it, seem to say to traditional fine artists: Look out behind you.

Got a question? Email [email protected]. Glenn Adamson is head of graduate studies at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and co-editor of the Journal of Modern Craft.