Tom Loeser: Taking Creative License

Tom Loeser: Taking Creative License

Tom Loeser's explorations of form, function, and dysfunction have placed him at the far borders of tradition, and he revels in it.

The bustling heart of Madison, Wisconsin, is nestled on the isthmus between Lakes Monona and Mendota. It is home to both the state's Capitol building as well as the flagship campus of the University of Wisconsin. Every fall, the neighborhood is besieged by students distinguished from their delegate counterparts by the unofficial uniform of the undergrad-anything red and displaying the university's mascot, Bucky Badger. State Street, the pedestrian mall connecting the Capitol building to the campus where musicians and jugglers abound, is lined with family-owned shops selling handmade crafts and staid galleries showcasing traditional Wisconsin craft work by local artisans. The crowded thoroughfare also proudly lays claim to the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art. The dichotomy is extreme, to say the least.

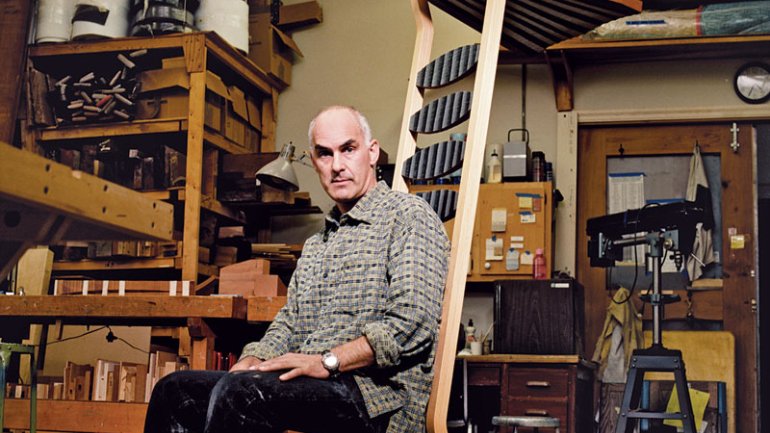

This intersection of craft and conceptual art may seem incompatible, but to a continually expanding number of people the combination of the two is intoxicating. The furniture maker Tom Loeser, an advocate of such intertwining, works just steps away, quietly plying his trade in his woodworking shop, producing pieces that seem to defy both the furniture category, in which he is usually included, and the art world of which he has become a part.

When the 52-year-old Loeser first took a position in the woodworking department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, in 1991, he didn't entirely understand what that meant. Seventeen years later, now a professor and head of the department, he is ensconced as one of the premier studio furniture makers in the United States, quite aware that he has been given the rare opportunity to meld fine craft with conceptual thought. The university perceives his work as original creative research comparable to that of a scientist working to unlock the mysteries of climate change in the age of global warming. His unique position as an artist coming from a woodworking background has inspired him to look deeper into his craft. His explorations of form, function and dysfunction have placed him at the far borders of tradition, and he revels in it.

"I don't know if I want to use the term responsibility, but I certainly have the chance to do different things because I don't have to make my living strictly from my work," Loeser explains. "I still love working from my background in the craft tradition, but I sort of enjoy bumping against the edges."

Lately, Loeser has been experimenting with found object installation, a process that has exposed him to seemingly endless creative possibilities. In the summer of 2007, for an exhibition in northern Wisconsin just outside of Minocqua, Loeser participated in a series of events called Forest Art Wisconsin. Taking on the notions of nativeness and invasiveness, Loeser collaborated with his wife, fellow artist Bird Ross, on The Rest of the Forest, a piece consisting of groups of ready-made chairs placed in different configurations to introduce hikers to social conditions unfamiliar to the forest. It invited individuals to become a part of the ecosystem of the area-they were each given their own place in nature to cohabit with other hikers. This piece was a direct descendant of an installation Loeser had created in Darmstadt, Germany, in 2004 called Forest Furniture. In Germany, Loeser produced rustic-style seating by making segments of chairs and benches out of saplings, which he then mounted on existing trees in the forest-actual tree trunks were employed as chair legs or backs of benches. Both installations were intended to give hikers a place to perch while encompassed by the forest, but through the installation in Wisconsin, Loeser allowed himself to relinquish the construc tion of the furniture and concentrate on the concept of the piece. "I really liked working more quickly," Loeser explains. "I come from a background of meticulous crafting, but it can sometimes be a problem. With woodworking, once you are taught fine joinery it's very hard to ignore it and go back to cruder techniques."

Loeser has been taking full advantage of this creative license. As an academic, he recognizes himself as a subversive in the field. "I think the woodworking world is too small, too limited and too defined by Fine Woodworking magazine. There is a slightly anti-intellectual slant to it. I am more interested in the ideas behind it and opening things up. I am interested in where we overlap with design and where we overlap with art." Loeser has always worked from historical objects and sources, but he plays with ideas of function by deposing the users' operational expectations. These days he welcomes escapes from his studio furniture oeuvre to explore other systems of generating form.

For the Wisconsin Triennial in 2007, for instance, Loeser proposed an installation titled Cinch. He had started playing with the idea of using industrial felt cinched with steel straps to create benches that attached to the columns in the entrance of the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art. "I had never really done anything like it before," he says. "I only had a certain idea of how to work with those materials. There were a lot of questions about how I was going to do it, and if I'd had to bet money, I'd have bet they would not have worked out as well as they did.

"I just like doing new things," he continues. "It's challenging to throw yourself into different kinds of water to have to figure things out. It's a little like when you give an assignment-you over-challenge your students and ask them to do something they've never done before and then you see how they resolve it. It's a good thing to do to yourself as a maker."

Loeser hasn't completely given up on meticulous crafting. He recently revisited his first love, wood, through works that are not necessarily sculpture, but also not necessarily furniture either. In Flotilla, his latest series, he investigated a new system to generate form, one that uses traditional boatbuilding techniques. The construction system used by boatbuilders is much different from most furniture construction systems, especially for its consideration of curved forms. Loeser became interested in boat construction after Josh Swan, a master builder, held a residency in the woodworking department at Madison in 2005. While in residence, Swan walked the department through all the steps necessary to construct a 13½-foot Maine "peapod" rowboat. "While we were working on the boat, we basically organized the stations on a straight line on a wooden platform," Loeser remembers. "We started to think about how it would be really fun to make a boat that isn't straight, " and his Flotilla series explores that concept. The pieces are smaller than conventional vessels, suggesting sculptural models for boat designs that would never be built.

Prior to the Flotilla series, Loeser had never created work that was primarily sculptural. "Flotilla starts to make sense to his larger body of work. It is an exploration of possible, yet somewhat outlandish, functional forms," explains Matthew Hebert, assistant professor of furniture design and woodworking at San Diego State University. Hebert, who has worked extensively with Loeser and recently wrote the catalog for the Flotilla show at Mobilia Gallery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on view this past September, has been witness to Loeser's evolution. "Through Forest Furniture and Cinch, Tom has really found a way to make simple augmentations of found forms in order to create the potential for inhabitation. This is another play with function."

"I think as an informed object maker today you have to know a lot of things," Loeser explains. "You have to think about and be aware of everything that is going on in the world that relates to what you are doing. It gets worse with the Internet because there are fantastic blogs. I do think that as a maker you have a certain responsibility to fit your own creative ideas into the larger world out there."

Looking back, Loeser admits that he is most enthusiastic about his recent pieces. "I love my job and I love what I teach. There are programs that teach furniture making and woodworking, but they are often treated as being limited to the craft area. What I like about the woodworking department at Madison is that we think about ourselves as an art department. I like the way my students and I are incorporated into the art dialogue." Loeser explains that when he got out of school, he had a woodworking shop for about nine years. "I just did woodworking. For long stretches of time you are just working in your shop by yourself and that is non-eventful. I like the social aspects of the university. I don't think I'd be that good just being a solitary artist and thinker."

The city of Madison is always overflowing with students scrambling to uncover their own path to a future outside academia. Every semester Loeser takes a select few under his wing and challenges them with questions that explore the world that exists between art and craft as he continues his own dialogue with form, function and dysfunction. Comfortably situated in the relative wilds of Wisconsin, Loeser happily straddles the line between art and craft that many feel is uncrossable. In the process he has helped to redefine the current cultural conversation surrounding the fields by challenging the traditions of both.