Tools from the Sideways Universe

Tools from the Sideways Universe

“Be regular and orderly in your life, like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work,” novelist Gustave Flaubert advised artists. It’s one of Howard Jones’ favorite quotations.

“You can be a regular sort of person and live as an artist,” says Jones, a genial, plainspoken man who crafts startling, absurdist art in his garage on a quiet suburban street in Middle America. “You don’t necessarily have to always be avant-garde in every aspect of your life.” He pauses, then adds, as he often does, “Does that make sense?”

Jones’ sculptures make sense, until they don’t. At first glance, they appear to be familiar objects – hammers, shoes, chairs. But there’s always a bizarre twist: The hammer has four handles and four heads. The high-heeled pump is double-footed. The chair’s seat is made of hard, spiky sweet-gum seedpods. With their surreal imagery, sly humor, and strange beauty, his eccentric implements are pleasantly unsettling, prompting us to consider our relationships with the tools of daily life.

Tools have an intention that is part of their being,” says Jones, who has always loved them. “They’re made to do something. Often it’s to be an extension of us, if that makes sense – like a shovel is better than digging with your hands. I’m just giving them a different meaning by altering them a little bit.”

He combines found objects with parts he builds out of materials such as brick (“I like brick; it’s a real humble sort of stuff”) or wood (“2-by-12s, not fancy”). Brushes and shoes are his favorite forms to reimagine. He’ll take a used, spattered commercial paintbrush handle and replace the bristles with typewriter keys or affix bristles to an antique wooden crutch. (Not surprisingly, housepainters get a kick out of his work; a painting contractor’s magazine once featured him on the cover, “which was very kind of them. I was in the caulking issue,” he says proudly.) Often, he’ll repurpose odds and ends from around his house or yard, things that hold meaning for him. When his daughter went off to college, he attached a tangle of roots to the soles of the saddle shoes she wore as a kid, a poignant reflection on growing up and letting go.

Our experience of Jones’ art is visceral, sensory. We put ourselves in his cast-concrete Rocking Shoes (2002), a pair of lace-ups on curve-bottomed blocks, and imagine being at once in motion and stuck. A paddle made of bricks suggests the heavy, tiring work of canoeing. Boots with scrub brushes for toes evoke the silly sensation of sweeping as we stroll. How would it feel, we wonder, to wield a shovel with a snake-like handle? What could we chop with a triple-bladed axe?

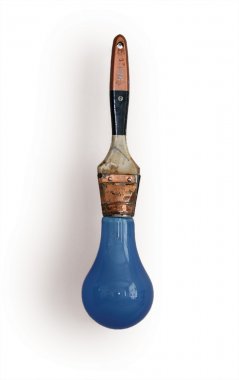

Then there are the psychological dimensions of these dreamlike pieces, things that make us go “hmmm.” A paintbrush of thorns (from the bushes in front of Jones’ house) conjures a dark fairy tale or biblical agony. Other brushes seem to comment on the nature of art, through such elements as a rusty grenade (explosive potential) or a pink light bulb (illuminative power). Rifle shell casings filled with fine-tipped bristles resemble lipstick tubes, alluding to sex and danger. Interpretations of his art often surprise Jones, and he likes that. “I welcome it. I don’t know that, once I’m done with a piece, that it’s done, intellectually or conceptually.”

His work may be a trip, but Jones’ own journey has been pretty normal. He was born in Pittsburgh in 1954 and spent his early childhood in Ohio. When he was 9, his family relocated to Connecticut, where his father, a business executive, and mother, a homemaker, encouraged his interest in art. In his teens, he would ride the train into Manhattan to visit the great museums.

“That was a regular thing to do. You’d walk up Fifth Avenue, go to the Whitney, the Guggenheim. I remember seeing Picasso’s Guernica when it was still at the Museum of Modern Art.”

After he graduated from Kenyon College with a degree in studio art and humanities, he married (his wife, Barbara Smythe-Jones, is a public relations consultant) and earned an MFA in painting and printmaking at Ohio University in Athens. There he honed his printmaking skills working on the Trisolini Print Project, where he collaborated with well-known artists such as Robert Stackhouse, Nancy Holt, and Tom Doyle to create original editions. In 1983 he settled with his young family in St. Louis to work at Washington University, making prints and drawings on his own time and eventually working as a freelance printmaker, earning a reputation as a master of the craft.

By the mid-1990s, he was ready for a change. A studio fire a few years before had put an end to his printmaking, and he began teaching art at a private high school, but drawing no longer fulfilled him.

“I was marking time, thinking about how long it would take to draw that thing – a curtain, a dress, a lemon, whatever,” he says, recalling how composing such elements on paper had once excited him. “A challenge became, it seemed, a burden.” So he switched to making objects, which proved “equally intriguing, but more immediate, even if ultimately they required as much attention,” Jones says. “Some of these [pieces] I think of as drawings, in a way – flat, wall-based things, almost like collages, combining elements at my whim.” While he continues to draw – figures, still lifes, variations on his sculptural themes – the objects are “the most satisfying stuff I’ve made.”

Recently retired from teaching, he’s enjoying the freedom “to travel and do things without a calendar in the way. I’m making good use of my time in the studio.” The Joneses live in a 120-year-old house (“clapboard-sided, straightforward, an upstairs and downstairs, not a lot of ornament”) where he gets to ply his tools on the upkeep of an older dwelling. (“You’re never done,” he sighs.) After 35 years in the Show-Me State, he considers himself Midwestern in his sensibilities. Is there a link between his Rust Belt roots, heartland home, and the motifs of industry, farming, and labor that abound in his sculptures? Not that he’s aware of, but Jones is open to the idea. “That’s not bad. I kind of like it, actually.”