Two Threads

Two Threads

Jo Hamilton was just 6 years old when her Gran taught her a basic crochet stitch. For years afterward, Hamilton, growing up in Busby, Scotland, crocheted clothes for her dolls and, later, hats for friends. “I love all the different yarns, the colors and textures, and how the process is so meditative,” she says.

Hamilton dreamed of becoming an artist, so she studied drawing and painting at the Glasgow School of Art in the early 1990s. “I wanted to do representational work, to relay meaning,” the 43-year-old artist explains. Hamilton painted for 20 years, but grew dissatisfied with the results. “I wanted my paintings to be richer, to be more than what they were,” she recalls. “I couldn’t figure out how to work with several colors simultaneously to make the images more textured and alive.”

Then, in 2006, Hamilton saw a show where embroidery was appropriated for fine art. “I wondered: Could I combine my two loves, painting and crochet? Could I crochet a painting?”

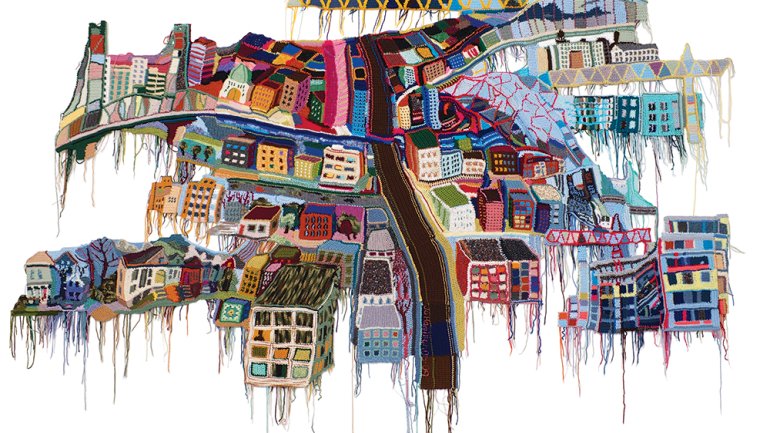

She decided to try with a cityscape of her adopted hometown of Portland, Oregon, where she had taken some classes in 1995 and relocated the next year. Beginning with simple geometric shapes, Hamilton stitched baby-blanket blues and pinks next to knobby beige yarns, accented with veins of bright red. Hamilton’s community of local artists was startled by the results. “You’re really onto something here,” friends told her.

At the time, Hamilton was supporting herself as a server at a French restaurant. As she developed I Crochet Portland, her co-workers at Le Pigeon teased her about the project. So she threatened to crochet them. “Then I wondered if I could get a good likeness with yarn.”

Hamilton started with the pupils of a cook’s eyes, moving outward to the iris, the lashes, the lids, using the stitches to describe the form, like the brushstrokes in a painting. When she stepped back for a look, she laughed. “I couldn’t believe it; those were Will’s eyes. And they looked so alive, so real, so expressive.” With only snapshots to guide her, she crocheted portraits of her whole restaurant community of 16 people – servers, dishwashers, and cooks. “It became very clear, very quickly, that not only could I capture a likeness, but also expressions and emotions,” she said.

Over the next few years, Hamilton made likenesses of women wearing masks, a riff on “Who is that masked woman?” as a way to depict the heroes they often are in their communities, along with crocheted portraits of residents, staff, and volunteers at a residential AIDS facility. She also replicated mug shots. “It was exciting and mysterious that I could capture with yarn what I could never accomplish with paint,” she says. And she’s proud that her work has become part of greater movement to elevate traditionally female crafts, which she says are too often seen as inferior or unimportant.

These days, Hamilton crochets paintings full time, eight to 10 hours a day, sitting on a futon in her home studio with floor-to-ceiling shelves of yarn, her rescue terrier Dougal nearby, and a good movie running. With all the unraveling and re-stitching Hamilton does, a piece can take hundreds of hours.

It’s a long process, but she doesn’t mind. “There is something profound about spending so much time with someone’s face, someone’s features,” she says. And even though Hamilton works long hours alone, she doesn’t feel lonely. “I’ve gotten huge amounts of support from the craft community, people writing to me saying that they’ve been crocheting for 40 years and have never seen anything like this, people saying that my work has made them cry,” she says. The internet community has embraced her work; her photos and videos have been picked up on sites all over the world. The Portland fine arts community has opened its arms as well. In 2013, the Laura Russo Gallery began representing her and recently hosted a solo show.

“Now that I’ve proven that I can represent anything I want,” Hamilton says, “I want to play with more abstraction and push that boundary.” She’s also writing a grant to make the first crocheted mural in Portland, possibly on SE Division Street, not far from her studio.

“I’ve always wanted to figure out a way to make my art public,” she says. “I think there’s a sense with public art of common ownership – everyone can see and enjoy it; it belongs to everyone.”

Elizabeth Rusch is a writer in Portland, Oregon.