Unnatural Selection

Unnatural Selection

When reckoning with such intractable issues as climate change and humankind’s often turbulent relationship with the animal kingdom, it helps to have a sense of humor. Laurel Roth Hope has that and more. With the eye of a naturalist, the curiosity of a scientist, and a self-taught mastery of a range of materials, she illuminates everything from the peculiar practice of designer pets to the tragic demise of the dodo.

With her husband and occasional collaborator, Andy Diaz Hope, 51, and their 1-year-old daughter, Juniper, the artist lives in San Francisco’s Mission District in an Edwardian-era home behind red gates. She grew up one hour north in a rural town called Two Rock, where solitude helped foster a deep communion with nature. “There were no kids around, and I basically ran through the sheep fields among the blackberries, taming feral cats,” recalls Hope, 45. She began working in computer animation at 21 but, a few years later, found greater fulfillment working outdoors, first in conservation and later as a park ranger for Marin County. Cleaning up the beach one day, she spied a billiard ball washed up on the sand, a discovery that led her to take up carving.

“I found myself fascinated by these man-made things that don’t break down for millions of years and the idea of altering that process. So I bought a Dremel [rotary tool], taught myself how to use it, and started carving animals out of bits of urban detritus,” says Hope, whose career has been marked by an unusual openness to new techniques. In 2005, she and Andy, who was working as a product designer, took sabbaticals from their jobs to focus on art for six months – which have stretched to 14 years and counting.

Of particular interest to Hope is how the long, slow process of natural selection has been supplanted, subverted, and sped up by humans’ desire to control and dominate their environment, altering the course of evolution. Man’s Best Friend, her 2006 – 08 series of pet skulls, most of polished acrylic that resembles crystal and amber, includes breeds that, to their detriment, have been manipulated for our aesthetic pleasure. “French and English bulldogs can’t give birth or reproduce naturally; Persian cats have trouble breathing; Great Danes’ hearts can’t handle their size,” she says, citing just a few examples.

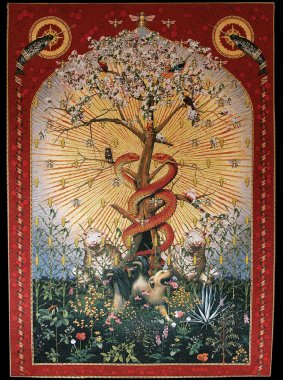

From 2008 to 2013, the couple collaborated on a triptych of jacquard wall hangings inspired by the 15th-century Unicorn tapestries. The first, Allegory of the Monoceros (2008), creates its own iconography to describe the end of Darwinian natural selection and the growth of human-centric evolution. Dolly (the first cloned sheep) gambols; Cerberus – whose three heads represent Snuppy (the first cloned dog) and his genetic and birth parents – guards the foot of a biblical apple tree with a branch structure based on Darwin’s Tree of Life. A reflection, in part, on the species that lose out in the new world order, this tapestry has two narwhals in the border; they’re one of the marine mammals most likely to disappear due to climate change.

Birds make especially ideal models for Hope’s musings on adaptation, extinction, and human behavior. “Because birds are the one non-domesticated animal that even city people are likely to see every day, it makes them particularly ripe for exploring our relationships with nature,” she explains. Flight of the Dodo (2013), a gilded bas-relief in the Renaissance tradition, depicts the dodo as a comical martyr ascending to heaven. The doomed bird is borne aloft by seraphim pigeons, whose winged adaptability allowed them to proliferate, whereas the dodo, flightless and guileless, was quickly wiped out once European colonizers discovered its island idyll.

Hope began her Peacocks series in 2008 with materials procured on eBay and the 99 Cents Only store. The birds are constructed from accoutrements typically associated with human female “plumage,” such as artificial fingernails, barrettes, fake eyelashes, and costume jewelry. The birds’ postures are intentionally ambiguous: It’s not always clear whether they are mating or fighting. “A lot of my work looks at the fact that humans engage in much of the same behavior as other animals – competing for food and a mate – and we also use our plumage to signal availability and desirability. It’s interesting to ponder how our presentation informs our perceived value and mating potential,” she says.

Carved pigeons are the mannequins for her Biodiversity Reclamation Suits for Urban Pigeons, with markings crocheted in cotton, wool, and silk thread to resemble vanished species such as the Seychelles parakeet, Cuban red macaw, and ivory-billed woodpecker. “It’s funny how the things that adapt to us most easily are often regarded as pests,” she muses. “Pigeons are present in most of the world’s cities and likened to rats. So I wondered, ‘If you put the suit of a Guadalupe caracara on a pigeon, does it make it more valuable?’ Or maybe it comforts us, because, voilà – there’s biodiversity again!” The works are in several permanent collections, including at the Smithsonian, which awarded Hope an Artist Research Fellowship in 2017.

Another avian-themed residency was at the Kohler factory in Wisconsin. The company, best known for its porcelain plumbing products, supports a program that fosters the intersection of creative practice and industrial process. With little experience in clay, Hope wanted to learn how to slip-cast porcelain starlings for future projects. Sixty starlings were released in Central Park in 1890 thanks to a group importing old-world flora and fauna; Hope sees a parable of Manifest Destiny in the explosion of what is now an invasive species, with a North American population of more than 200 million – all competing with other birds for food and nesting sites. “It’s such a strange idea: Humans come to a new country, dominate the landscape and people, and import what’s familiar instead of learning about what’s already here,” she says, “which we now know is a pretty terrible idea.”

The ceramic birds have alighted in several projects, including a circular cluster called Seraphim Murmuration (2017), named after the phenomenon of thousands of starlings swooping through the sky in intricately coordinated patterns. A halo of glazed and gilded starlings circle a clay gorilla in Reliquary for Biodiversity (2019), a rumination on how individual strength provides no guarantee of biological success in the Anthropocene era, when poaching, war, and habitat destruction threaten the ape’s existence.

Hope’s work brings to mind the trenchant thoughts of novelist Jonathan Franzen: “What bird populations do usefully is indicate the health of our ethical values. One reason that birds matter – ought to matter – is that they are our last, best connection to a natural world that is otherwise receding.” Her creations confront many of the same issues, and at the end of the day, she considers herself not so much an “animal artist” as a humanist. “It’s interesting that my work puts me into a subset of ‘artists that do animal work,’ ” says Hope. “Rather, I believe we live in a world with all kinds of things that affect each other. But we humans are so inward-focused that we barely see anything beyond ourselves. Sometimes it’s a stretch to consider people who don’t look or act like us, let alone the rest of the planet. But it’s there for us to learn about, if we only take the time, and it’s amazing.”