The Unvarnished Truth

The Unvarnished Truth

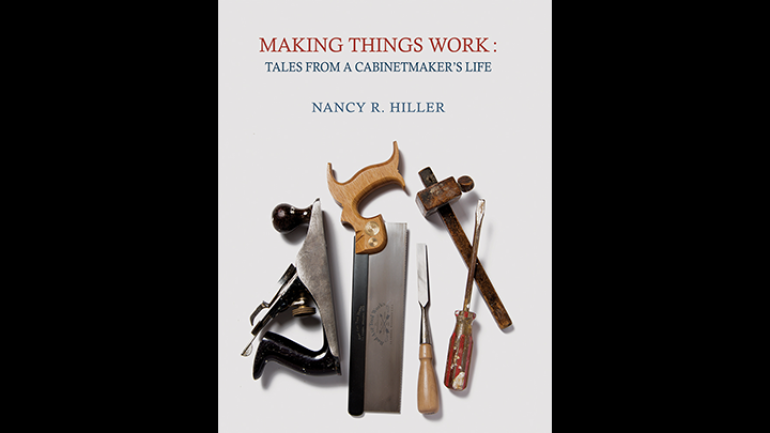

If you think woodworking is a quaint way to make a living, Nancy R. Hiller has a few words for you. In fact, she’s got a whole book dispelling that romantic notion. Composed of frank, entertaining anecdotes drawn from her almost 40-year career, Making Things Work: Tales from a Cabinetmaker’s Life lays bare the business of craft. The Indiana woodworker, author, and business owner, 58, talked with us about the cost of perfectionism, the art of customer service, and overcoming doubt.

Why did you want to write this book?

There are a lot of magazines and books about how great it is to make things for a living, and furniture making seems to be one of the most sought-after modes of making things today. All the cool people are furniture makers, right? But who’s buying all this furniture? [Laughs.]

I get tired of the relentlessly upbeat, fantasy-based romance of furniture making. And for years now, I’ve been wanting to write a serious book on this subject. The other motivation is to present a grittier version of reality.

I also wanted to give customers – people who don’t necessarily make things for a living – a glimpse into what goes into making stuff, by way of helping to explain why things cost what they do. I’m always trying to do my work as affordably as I can, and so I always bring up the budget. Budget and timetable are the first two things I ask about when somebody contacts me [about a project], because if I can’t do the work for something approaching their budget, or if I can’t do it within the time frame they want or need, then we’re not going to be able to work together.

Sometimes it is worth getting together with people and talking, because even if you don’t get that job, they may keep you in mind for something down the line. Or they may refer somebody else to you who ends up being a great customer. But I’ve learned over the years not to be shy about talking about money, because you have to, if you’re going to make your money at something. There’s no getting around it.

How did you get more comfortable talking about money?

My line of work is very solitary most of the time, and a lot of the time I’m doing repetitive tasks. Even if I’m doing a custom piece, there’s still a certain amount of sawing and sanding. So I talk to myself – not literally, not out loud – but I’m constantly having some kind of silent conversation. And basically – I became my own therapist. [Laughs.]

I would reason through things. I would pretend that I was talking to someone else, and think, “Why would you feel that you’re overcharging someone when all you’re charging is what you need to make a living and pay your bills and run your business legally? Where is the logic in that?” I mean, if they can’t afford you, then you either need to figure out a different way to run your business or you need to develop a different clientele who can afford you.

In a few stories, you battle your inner perfectionist. Why was that important to address?

There’s an expression in the building trades, in contracting: “Done is good.” [Laughs.] That is, “Get it done.” “Done” is good – don’t worry so much about “perfect.” People go on and on about perfectionism and they get very romantic about it. And I get it; I totally get it. That’s the way I was trained. But at a certain point, aside from the fact that you have to make a living, there’s also a gross pridefulness that sometimes accompanies that kind of perfectionism. I wanted to say that sometimes a thing doesn’t actually need to be perfect in order to function perfectly well – because it’s true.

And then, of course, sometimes I’m not able to redo something until it’s perfect, because my clients aren’t going to pay for perfection. I have to make a living and don’t have all the time in the world. So I wanted to put that side of the argument out there, because when it comes to craftsmanship, that side of the argument is rarely made. [Laughs.]

People do have very strong opinions about it.

And I love the imperfections. That’s one of the things I absolutely love about things that are handmade.

Would you say perfectionism is something that you learned in training or is it just a part of who you are?

I think it’s both. It’s partly that there is a tenaciousness to my personality, and lots of people have this – it’s almost a kind of compulsiveness or obsessiveness. But at the same time, craftsmanship encompasses this striving for excellence. So it’s innate, possibly a pathological condition, and something that is cultivated through training. That’s really what craftsmanship is. You’re constantly saying, “Do I think it’s good enough?” There’s always this implication that “it could be better.” It’s implied. It’s like you’re training to be neurotic. But that’s part of craft. [Laughs.]

What do you love about cabinetmaking?

Well, there’s the whole sensuous aspect of it. The smell of wood – I mean, not every wood smells good. But I’m one of those people who love the smell of [a kind of] elm – some people call it “piss elm,” and other people think it smells like poop. It’s very earthy, and I love that. I love the smell of sassafras, which smells peppery or like root beer, depending on the tree. And it is a beautiful material. It is really satisfying to clean up a piece of wood. And I like being able to move. It’s a job with a certain amount of physical activity.

But really, another one of my favorite things about it is that it’s a kind of wizardry to be able to come up with an idea, draw it, and then turn it into a three-dimensional reality. That is something that never gets old for me. Maybe it’s because I consider myself, ultimately, not a very capable person, but there’s something wonderfully surprising about being able to take an idea out of your brain and turn it into reality, and then have that object meet you as part of your external reality.

Another thing is I love my clients! They allow me to make a living and they give me the great honor of coming into their houses and working with them to make their daily reality more pleasing, their most intimate spaces. They write me notes and say how special it is that they had this interaction with me and how wonderful it was to go through that process and have the opportunity to live in the space that we imagined and created together. That is a gift, to be able to do that.

It sounds like those relationships are a big part of your job.

Right, and like any kind of relationship, there are always going to be difficult times, and you have to be patient with your clients.

There are some people who aren’t empathetic and who aren’t patient and who aren’t interested in the client relationship, but I don’t see how you can do custom work and not be. And then there are people who’ve hired me, and we have a contract, and I’m halfway through building their thing, and they’re just incapable of being pleased, apparently – or at least, what I’m doing is not pleasing them. There have been a couple of times, in those situations, where I realized it wasn’t worth it, and I would just say – very calmly and respectfully – “I would like to return your deposit, and you can have someone else make your whatever,” because I’d rather do that than have them be unhappy with the work.

There are some people out there who are unreasonable, and when you’re in any kind of business, you have to figure out how to deal with it. Every contractor with whom I’m friends, we have these conversations. There’s like this collegial therapy club. [Laughs.] The conversation will go to these places, and you’re like, “What did you do? How did you get through that?” It’s very helpful to have those conversations, because for one thing, it makes you realize it’s not just you. Other people have these things happen. You realize that there’s a whole other dimension of craft, and that is the craft of the relationship. And sometimes the relationships end badly, but there’s still a craft to ending them. [Laughs.] It’s also important to try to comport yourself as a decent human being, for your own sake.

What do you think is the hardest part of running your own business? Is it the lack of a stable income?

No, I wouldn’t say the lack of stability, because in a way, lack of stability is good – it’s good for a personality type such as mine, in that it keeps me on my toes and challenges me to be resourceful. I feel like Making Things Work is about some of the worst things. [Laughs.] The whole book is about the bad stuff, as well as the good.

Many people think creative work is all fun and games.

But it’s also work. It’s like a pregnancy – I’ve never been pregnant, quick disclaimer here. But I can only compare it to that, because in between the joy of conception and the joyousness of holding the infant in your hands, there is plenty of morning sickness and there are plenty of trials, and there are delays. There are frustrations. There are often multiple situations where I’m like, “Oh man, I thought I had figured that out and I haven’t figured it out.” There’s problem solving. You make mistakes and have to redo or correct that part of the job. There’s all kinds of stuff like that that’s frustrating. But after you’ve been doing something long enough, you realize that.

Another thing is the self-doubt that sometimes will happen. Something can take way longer than I expected it to, and I think, “I don’t know if I can actually pull this off. I shouldn’t have said I could do it.” [Laughs.]

Right, but then you have to.

There’s a certain point [of the creative process] I call the nadir, the low part of the bell curve. You’re at the bottom, and you’re like, “Holy crap, I don’t know if I’m going to be able to figure out how to get through this.” But then you get through that point a couple of times, and the next time you feel that sense of panic rising up in your psyche, you are able to tell yourself, “Oh, this is my old friend. I remember this, and I will get through it. I’m not sure how, yet, but I will get through it.” That is one of the good things about aging: I know I’m going to figure things out; I have the confidence that it will come to me.