What Responsibility Might Look Like

What Responsibility Might Look Like

Q: Is there a sustainability aesthetic? If so, how would you describe it, and which artists exemplify it?

A: I recently curated an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum on postmodernism. The show focused on the 1970s and ’80s, when modernist convictions were overturned in favor of gleefully self-referential superficiality. When a modernist designed a chair or a teapot, the intention was usually to improve the life of the user. The idea was that a perfect object might bring about an equally perfect world. The postmodern impulse was different. Its practitioners realized that in an age of television, film product placement, and glossy magazines, it was the image that really counted. Just one outrageous object could make waves in the international design press.

This may seem like an odd way to launch a discussion of contemporary sustainability, but it’s actually a crucial part of the story. As the 1980s wore on, exhaustion with postmodernism began to set in. What replaced it was not just modernism redux, though. Designers and craftspeople started thinking about issues beyond style, and a new ethical consciousness emerged. These makers in the post-postmodern movement retained a keen self-awareness about the potency of images, reasoning that if every object is a promotional opportunity, how it signifies values such as sustainability is as important as whether it is itself sustainable.

There is an obvious trap here: It is all too easy for makers to congratulate themselves on appearances. The humble roadside pottery, for example, seems to be at one with nature but is actually recklessly inefficient in terms of fuel and materials. Huge factories produce functional tableware at a fraction of the environmental cost.

Even so, artists are becoming much more sophisticated in their understanding of sustainable production. Some turn to environmentally friendly materials such as bamboo or locally made yarns. Patient sourcing is a key practice of contemporary DIY artists. Others “upcycle” the detritus of capitalist culture into new objects, or employ rapid prototyping systems like RepRap, in which used plastic objects are broken down and used to produce new, useful things.

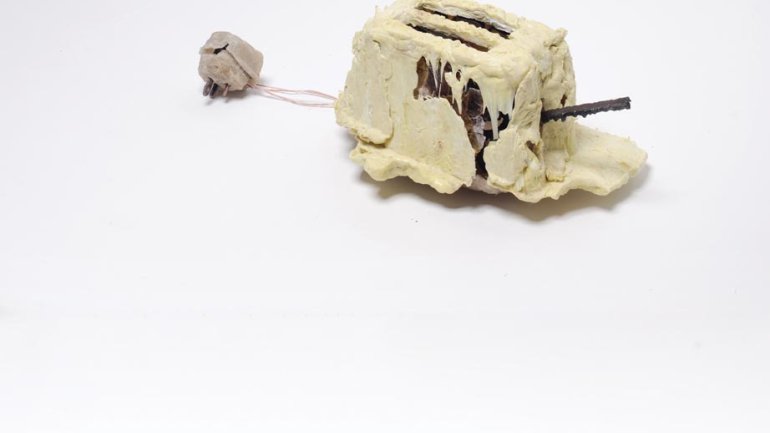

Metalsmith Gabriel Craig cites promise in “secondary refining,” in which metals already out in the marketplace are reclaimed so they can be forged anew. [See story, page 98.] And in one highly publicized recent experiment, the young British designer Thomas Thwaites tried to make a toaster from scratch. This comic work of conceptual craft dramatically illustrated the complete inability of consumers to make most of the things in their lives, even the simplest.

Of course, big corporations are just as adept at manipulating the rhetoric of sustainability as young makers. But craft does have a special advantage. In the effort to promote more self-aware ways of living, the simple act of making by hand signifies direct engagement with an object, and therefore a degree of personal responsibility. Certainly, not every craft object is made sustainably; we have to get real about that. But the lesson of postmodernism is that the power of the image is not to be denied. It’s not enough to make things responsibly; we need to call on mass media to constantly remind the public of what responsibility might look like.

Got a question? Email [email protected]. Glenn Adamson is head of research at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and co-editor of the Journal of Modern Craft.