Why Craft Matters

Why Craft Matters

↑ Embroideries by Hripsime Zvart Vartanian, the author’s mother. The white embroidery is by his grandmother, Mariam Hamalian.

Photo: Courtesy of Hrag Vartanian

Making something from nothing is what craftspeople do every single day. Let’s call it magic because that’s what it feels like sometimes. The power of creation is beautiful to behold, but it’s rarely easy. It is informed by a lifetime of doing, thinking, and dreaming.

The role of craft in my own family can’t be underestimated. We hailed from three cities just north of Aleppo, Syria, during the Ottoman Empire. After the horrors of the Armenian genocide in the early 20th century, we found ourselves on the Syrian side [of a new border with Turkey], drawn by imperial powers, uprooted and disconnected from our hometowns forever.

Following the trauma of exile, starvation, and massacre, when most older memories of the genocide were buried, what my family retained was mostly their craft traditions. With no objects surviving along the way, it was what they knew how to make with their hands that did. My mother’s family retained the memories of these markers of identity – the craft skills, which varied from city to city at the time and thereby captured the colors, textures, and forms of a place they could never return to.

The 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry tells the story of the Norman conquest of England. The 230-foot-long embroidered work is housed in a museum in Bayeux, France.

Photos: © Bayeux Museum

I grew up with these items, often in the form of pillowcases and colorful needlework, draped on the backs of chairs and divans in our living room. The most precious objects were stacked away in drawers, carefully preserved to avoid moths and other critters, and pulled out like secrets that were shared periodically.

My mother learned these “secrets” in different ways. My maternal grandmother’s cousin, last name Charekian, taught her the needlework of the city of Marash, Turkey (today called Kahramanmaras), while her paternal grandmother’s cousin, Zarouhi Daghlian, taught her a type of needlework common to her town of Aintab (present-day Gaziantep), Turkey. And my mother is slowly sharing her knowledge with me. What does it mean to transition the knowledge of a craft? Who’s the audience? What if it’s an audience of one?

When I saw these embroidered objects as a child, I understood a type of joy and continuity that I wouldn’t have understood any other way. They were an integral part of our family’s visual universe.

So, when I first saw the paintings of abstract expressionism, like the work of New York artist Richard Pousette-Dart, for example, the visual world of my childhood with its varied textures, fine needlework, and brash colors was my frame of reference. I saw their shadow even in the work of the pattern and decoration movement in the 1970s and ’80s, not to mention the time I rushed through the Textile Museum of Canada when I was a little kid and saw what I thought I could recognize from the history in my own family. Those helped me swing the doors wide open, and the world of art felt more accessible than ever. They were familiar and represented a history that was never spoken – but felt.

...craft can also be a coded language, spoken in different registers to different people.

I saw how these objects snake through the world. For instance, my friend Nishan Kazazian, an architect, artist, and professor at Parsons School of Design, organized a show of Marash needlework in Beirut in 1972. Then, when visiting Istanbul in 2015, I encountered another example: artist and psychologist Dr. Anita Toutikian’s exhibition of her grandmother’s work, which built on these traditions. Her name was Hripsimeh Sarkissian. As Toutikian writes, “Hripsimeh could not speak about her pains openly, but her fingers did. She unconsciously weaved her life story into her embroideries. She ‘exbroidered’ her pain with thread on cloth and color in form, not knowing that anybody would ever be able to read them. At the time, people thought she was a little crazy, and they didn’t know how to read them. It took 100 years.”

So how do we read and write about and understand these objects? How can craft speak the unspeakable? Are they messages to the future? I understand Toutikian’s words deeply. They’re not unique, but universal – because craft is. Even rooted in local materials, histories, and realities, craft embraces the world and everyone it comes into contact with.

I called my mother and asked her why she made this kind of work. In her characteristic way, she dismissed my questions. “I thought they were beautiful,” she said. “And they gave me a sense of accomplishment.”

As her son, I know it’s more than that. It’s because she wanted to be a doctor when she was younger, but was prevented from doing so because of a family and a culture that thought her place was in the home. I saw how she used embroidery to create structure in her life – allowing herself to find comfort in rational forms – channeling her creativity and feelings into objects. She made a stunning hope chest for her wedding, complete with handiworks of all types. It was a celebration of herself, one avenue that society allowed her to embrace. It reminds me that craft can also be a coded language, spoken in different registers to different people.

↑ Scandinavian pacifist and self-trained textile artist Hannah Ryggen’s 6 October 1942 (1943) depicts the Nazi occupation of Norway and the execution of 31 citizens on October 6, 1942.

Photo: Anders S. Solberg, © H. Ryggen, BONO 2020

My friend Kazazian also wrote a paper on Armenian embroidery is the early ’70s, and for it he interviewed two genocide survivors from the same town: both 80-year-old women at the time. They explained to him that the textiles were folded and stored in alcoves in the largest room in the house, and when elderly women came to visit, they would look through and admire the work.

As Kazazian’s research suggests, these caches of carefully worked fabric were integral parts of the lives of women. He was told that a proud mother would say in the local dialect, “My daughter has many skills. She has a thimble-like mouth and lips like cherry. How could I give her to you? I cannot.” These are the stories we tell when we talk about history – the ones that modern art museums, in particular, don’t often want to hear. The women would gather together and sing when they work – their voices controlled, but fierce. They conjured up their own magic in the ways they were allowed. Their thimbles or mouths spoke.

For too long, we haven’t listened. The fact that craft has often been feminized and racialized in different ways is a travesty. The old hierarchies determined by medium and class are mostly useless to many of us. And there are new conversations happening now, which may not have been possible or even imaginable to people generations ago.

Following the trauma of exile, starvation, and massacre [of the Armenian genocide]... what my family retained was mostly their craft traditions. With no objects surviving along the way, it was what they knew how to make with their hands that did.

Massachusetts artist and filmmaker Talin Avakian is engaged in one such conversation. She is of Armenian, Nipmuc Nation, and African-American heritage and has had the great fortune of being exposed to each of her cultures. Into her powwow regalia, she even incorporated the needlework of her grandmother, who also originally hailed from Marash, Turkey. “Every family member always reminded me of the importance of knowing who I am and where I come from,” she says.

It’s not only artists who help us to see these connections, it is also curators like Lowery Stokes Sims. At a symposium at the Newark Museum, she mentioned Carolina Clay: The Life and Legend of the Slave Potter Dave, Leonard Todd’s great 2008 book and social history of pots and Dave Drake, the enslaved man who risked his safety by learning to write, even on the pots themselves. Today, his works are housed in great museums, but it is because of the work of writers, art historians, and others that they’re finally being given their due.

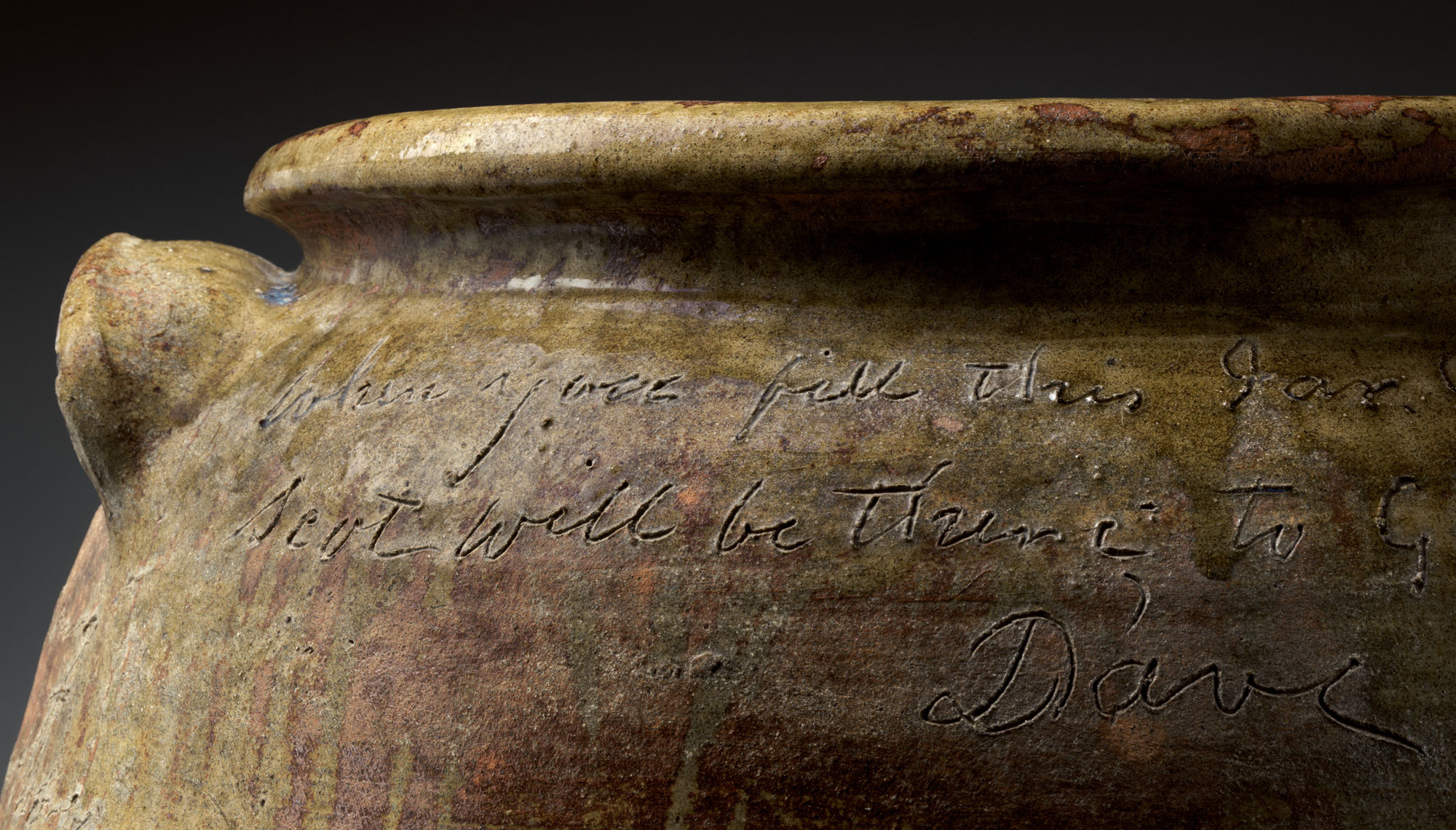

↑ A 19th-century jar by Dave Drake, an enslaved South Carolina potter and poet. By his own hand, the following poem is inscribed: “When you fill this Jar with pork or beef / Scot will be there; to get a peace.” At the time Drake made this jar, it was illegal for enslaved people in South Carolina to read or write.

Photo: Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

I can’t help but also think about the 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry. Its embroideries tell the story of the Norman invasions of present-day England. They help remind me that there is history in craft of all types, alternate histories that are often more inclusive of our past. I see these threads in the work of Swedish-born Norwegian textile artist Hannah Ryggen (1894 – 1970), who created large, allegorical tapestries attesting to her strong condemnation of violence, as the world burned through World War II and the Vietnam War. Technique blends with stories of violence to create impressive records of a moment in time.

Craft distills the world for us. It is a voice when few other things can speak. The way we discuss art must change to accommodate multifaceted stories rendered not just in symbol and line, but also in material. They are not windows, like we often think of artworks in the traditional European old-master tradition, but far more complicated things that transverse time, location, and faith.

Craft distills the world for us. It is a voice when few other things can speak.

Slowly, the tide against the myth of the individualist genius is shifting, understanding that it’s not only one person, but many who work together to create worlds before us, worlds that contain us all. This will not topple the importance of the artist, but it can subvert the pyramid where a few are on top and instead create a mountain range of peaks: many beautiful summits – all different, but connected.

Craftspeople are a force, providing a shelter with their work, ideas, and comfort in sensitivity. The craft community records our world – with every loose thread, shard of pottery, shaving of wood – and creates stories we may not be able to read yet, but will in the future. All I can do is use my thimble-like mouth to share what I’ve learned. I hope the craft community will continue to do the same with me.

Hrag Vartanian is the co-founder and editor in chief of Hyperallergic. This text is adapted from his keynote address at “Present Tense: 2019,” the American Craft Council’s conference in Philadelphia last fall. Listen to an audiorecording of Hrag's presentation.

Do craft stories like this matter to you?

Become an American Craft Council member, receive our magazine, and support nonprofit craft publishing. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about making, meet and buy the work of the country’s most talented artists at our shows, and help grow the number of lives craft has touched.