Wind and Wood

Wind and Wood

“They are, at essence, simple machines.” That’s what David Winigrad says of his wind-driven creations known as whirligigs. But while that may be true for the mechanically inclined – each piece is assembled using relatively basic combinations of propellers, ball bearings, cams, and shafts – to the ordinary viewer they are sources of no small wonder. Winigrad’s works spin in odd patterns, make strange noises, and come in shapes at once natural and otherworldly. They might be simple, but they’re endlessly captivating.

Whirligigs at bottom are simply any kind of spinning object, powered by mechanisms such as wind, string, or a propeller. They have a long history, says the 55-year-old Winigrad, and farmers have made them for centuries. His own output, though, is decidedly urbane. “Rather than have whirligigs where little characters were chopping wood or sawing or rowing boats,” he says of common motifs, “I thought, ‘Could there be a modern or contemporary take on this?’ ”

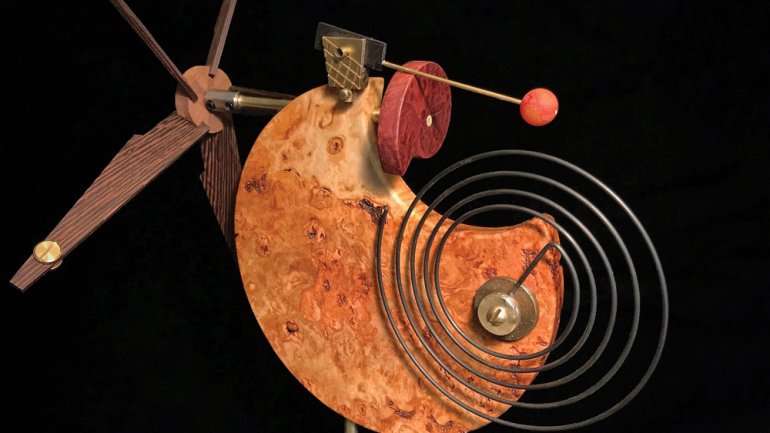

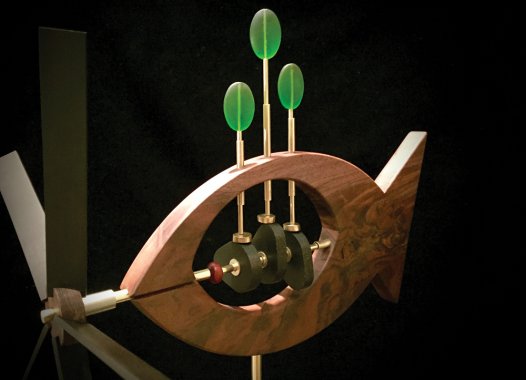

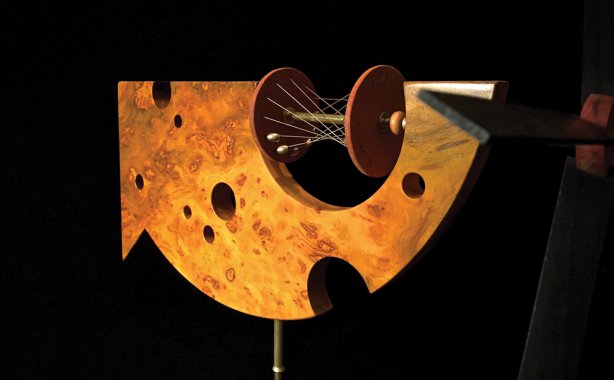

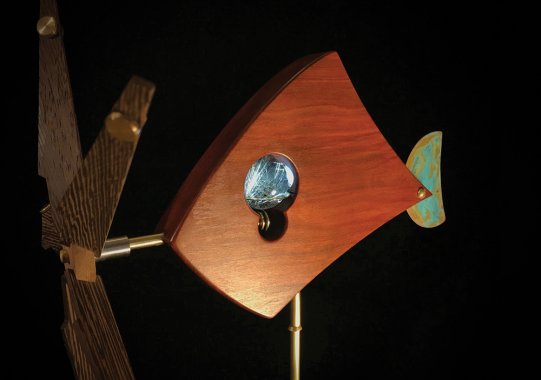

Yes, if his burgeoning career is any indication. Instead of miniature lumberjacks, the Philadelphia-area artist uses abstracted forms in a range of vibrant colors, which rotate within frames shaped like boats, fish, or waxing moons. Tang Whirligig (2018), for example, has a piscine body of redheart wood with a quartz marble set for an eye; the marble, illuminated by a concealed light, spins intermittently when the propeller moves. (“I use a lot of fish forms because fish tails are reminiscent of the weather vanes on traditional whirligigs,” he says.) The main attraction of Gong Moon Whirligig (2018), meanwhile, is both visual and auditory. In this piece, the propeller is attached to a camshaft that lifts and drops a hammer, striking a metal part Winigrad “liberated” from a cuckoo clock, which makes the surprisingly loud “GONG!” that gives the piece its name.

Winigrad, who runs his own online ad agency by day, knows how to command attention. “Movement attracts our eye,” he says. He credits the head-turning appeal of all those levers and spinning spokes for his success, at least in part. “Often, people see the work and say to me, ‘I’ve never seen anything like this at a craft show before.’ ”

Coming from an artistic family – his mother is a ceramic sculptor, and his father was a photographer – Winigrad has always had a creative bent. He studied two-dimensional design at Carnegie Mellon University and after graduating started working in graphic design, which eventually led to his current profession. But it was only after his brother handed down some woodworking tools five years ago that Winigrad started toying with the sculptures for which he has become known. While he has never taken a woodworking class, his design instincts make their way into his sculptural work. “Even though they’re three-dimensional things,” Winigrad says, “there’s a sort of flatness to them that I think I employ, this love of the tension curves.”

Still, working with wood offers Winigrad something 2D design never could: the chance to use his imagination to solve the puzzles that materials and making always present. He draws inspiration from the specific movement he wants to create and from the wood itself, he says, and often uses burls, bulbous and lustrous growths found on trees.

“By nature, they don’t have a straight grain; they don’t have a predictable quality to them,” Winigrad says. “They’re filled with voids and bark.” The imperfections can lead the design, as he incorporates the natural spaces or curves. “Even though I impose myself on the wood,” he says, “I do it in a respectful way, because the wood will allow me to do certain things, and it will not allow me to do other things.”

It is this sense of discovery, this ongoing challenge, that keeps the work fresh for Winigrad. He never quite knows how a piece will turn out. “What I learned, because my background is not in engineering, is: Things either work or they don’t work,” he says. “You have theories, and then you have what works. So I learned a lot through trial and error, and I experiment all the time.” Sometimes his pieces don’t spin correctly at first, some subtle friction in the mechanisms keeping them from running smoothly. And then, with the necessary correction made, they are freed – to respond to any small breeze, to catch the eye of any passerby.

Watch a video of Winigrad's whirligigs in action.