Enter Through the Gift Shop: Craft and Department Stores in Japan

From American Craft Inquiry: Volume 2, Issue 2

Where would you be most likely to go in search of exquisite handcrafted objects or clothing? If you live in North America or Europe, your first answer probably isn’t “the nearest department store.” The idea of Bloomingdale’s or Neiman Marcus selling handwoven baskets or lathe-turned wooden plates and bowls is about as implausible as it is thrilling. But in Japan, grand urban department stores (depāto) function almost like retail-supported craft museums. Venerable stores like Isetan, Takashimaya, and Mitsukoshi carry all the sorts of designer clothing, jewelry, accessories, and high-end cosmetics that you’d expect of a posh emporium. And in their basement-level food halls, you’ll find edible treasures like perfectly spherical watermelons and cantaloupes.

But in one key way, Japanese department stores are very different from their Western counterparts: They sell fine handcrafted goods by contemporary Japanese artisans, and in so doing, act as the bearers of a living, breathing craft culture that thrives alongside other kinds of commerce. Why is this true of depāto, and not of Western stores like Saks Fifth Avenue or Galeries Lafayette? The answer lies in Japan’s Edo period, an era during which it was relatively isolated from the West, and during which culturally specific ideals of merchant ethics were firmly established.

Department stores as we know them in the West sprang up as a natural consequence of industrialization. Their size and scale could accommodate variety and quantity, catering to the emerging European and American consumer classes at the turn of the 19th century. Scaled-up production and the proliferation of railway lines gave department stores in major urban centers access to coveted goods from near and far. In London, Paris, New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia, shoppers could find accessible luxuries such as perfume and cosmetics, hats and gloves, clothing, silver and china, sweets, and toys. The advent of in-store cafés and restaurants made visiting a place like Harrod’s, Le Bon Marché, or Marshall Field’s an entire day’s event that neatly bound together shopping, socializing, and dining in a grand public space. In the 19th century – Great Britain in the 1810s, France in the 1830s, the United States in the 1850s – department stores also offered employment and opportunities for advancement for women, which made them novel sites of both leisure and work at a moment when women’s emancipation was just taking shape in the West. Department stores were also among the preferred sauntering grounds of the flâneur, the gentleman of leisure who strolled, browsed, and enjoyed urban life as characterized first poetically by Charles Baudelaire, and later, theoretically, by Walter Benjamin. The flâneur (and later on, the flâneuse) had nowhere in particular to be but everywhere to be seen.

Department stores as such didn’t emerge in Japan until the end of the 19th century, and while they sprang up as a direct effect of industrialization, many stores that are still operating today trace their roots back much further, to the luxury dry goods shops that catered to the country’s urban elite during the Edo Period (1603 – 1868). During this era, Japan was isolated from the outside world, yet it experienced a stretch of relative peace and prosperity under the rule of the shogunate, or military government, controlled by the Tokugawa clan. The country was still rural and feudal, but, as its coastal cities grew, it was also increasingly urban and cosmopolitan, and the limited international trade it did have with China, Korea, and the Netherlands made its merchant class rich. In the strict Confucian social hierarchy of this era, those engaged in trade ranked below artisans, farmers, and the military, so newly wealthy merchants were largely excluded from the seats of political power, which was still dominated by Japan’s hereditary nobility.

But nothing prevented them from shopping, collecting, and engaging in increasingly luxurious and refined social rituals. This led to an artistic flourishing in which new art forms were born, and old customs, such as the tea ceremony, earned renewed interest as the country’s isolation inspired a reexamination of its own past. The visual legacy of activities during this period in Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo (modern Tokyo) are especially rich. Kabuki theater emerged at the turn of the 17th century. Formally designated pleasure districts, or yoshiwara, were the playgrounds of the newly-minted urban rich – possibly a deliberate attempt on the part of the shogunate to cordon these men off and distract them from the worlds of government and politics. By the end of the 17th century, the social whirl of kabuki performers, courtesans, artisans, and geisha in the yoshiwara were captured by the artists who made ukiyo-e, the block prints that captured the “floating world” of sensory pleasures for which they were named. Merchants bought ukiyo-e in droves.

By the turn of the 19th century, approximately 10 percent of Japan’s population lived in cities and large towns. Each administrative district in the country was controlled by a feudal lord known as a daimyō, who would hire samurai to protect his lands. Because the estates of daimyō generally didn’t produce their own goods, they were dependent on access to the works of skilled makers, and artisans flocked to the areas surrounding their lands. Merchants, in turn, provided the conduit to regional, and occasionally international, trade. Thus the grandest of Japan’s merchant houses were like the urban equivalents of a daimyō estate. And as non-aristocratic Japanese families acquired increasingly refined tastes, the retail landscape in the cities evolved to meet their desires.

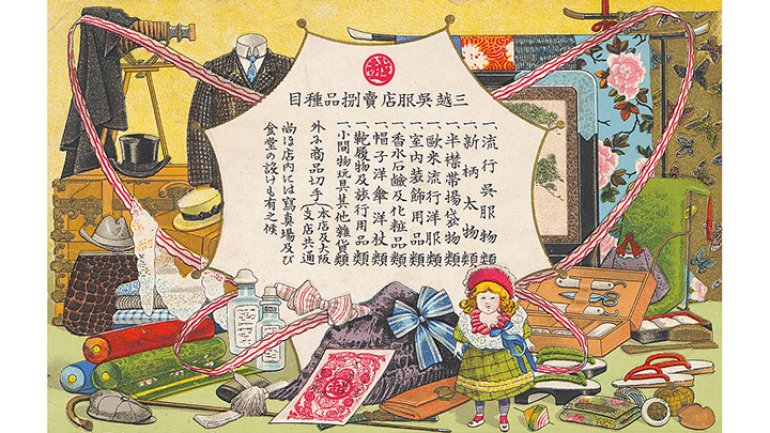

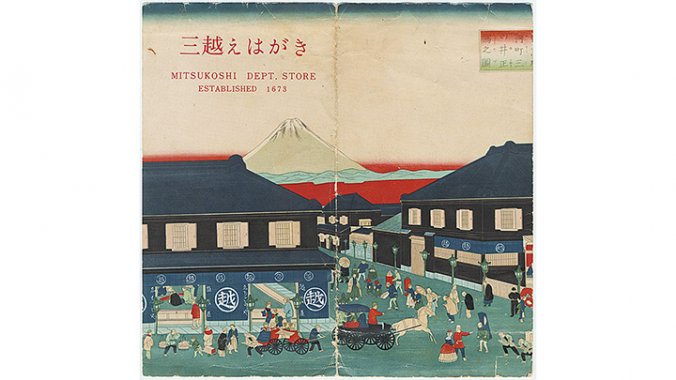

One of the most robust trades was in kimonos. In 1611, Ito Genzaemon Sukemichi opened a kimono and lacquerware wholesale business called Matsuzakaya, in the city of Nagoya. His descendant Ito Gofukuten shifted the firm’s focus to silk and cotton kimonos in in the 1730s. In 1740, Matsuzakaya became the kimono fabric supplier to the Owari Tokugawa – the most senior branch of the ruling Tokugawa family. The company that’s known today as Mitsukoshi was established in 1673 as Echigoya, and likewise began as a kimono business. Takashimaya first opened in Kyoto selling gofuku, or formal kimonos, in 1831. All of these companies developed national reputations and loyal customer followings, and in one corporate form or another, each still exists today.

Western powers had been vying for access to trade with Japan throughout the first half of the 19th century. Toward the end of the Tokugawa period, and following two naval incursions led by American Commodore Matthew C. Perry in 1853 and 1854, Japan’s rulers were forced to agree to trade with the United States, signing the Convention of Kanagawa. Other Western powers followed, and Japan’s political class was thrown into turmoil. The shōgun resigned, the Boshin War broke out, and a new, centralized government was established in its wake. Having been pushed into contact with the Western world in the 1850s, Japan’s new Meiji leadership set out to remake the country as a modern, industrial power.

A group of feudal lords who were historic enemies of the Tokugawa family formed a pact called the Satchō Alliance and worked to support Emperor Kōmei (1831 – 1867). When Kōmei died, his son Meiji became Japan’s 122nd emperor, and his six-decade rule gave its name to Japan’s new, modern era, the Meiji Restoration. The Meiji emperor represented a totally new iteration of Japanese power. He typically dressed in military garb, like one of the crowned heads of Europe, he oversaw the establishment of Western-style government reforms, and he pushed Japan to industrialize. But this adoption of certain Western practices didn’t mean that Japan’s culture would be lost. On the contrary, Japan’s new economic and military power meant that its culture could thrive and even influence the world beyond its shores.

The Meiji emperor was fond of slogans. Fukoku Kyōhei was a call to military might: “Enrich the Nation; Strengthen the Army.” Shokusan Kōgyō was pro-business: “Encourage Industry.” Bunmei Kaika was a general statement of ideals, and perhaps the most important of the three: “Civilization and Enlightenment.” Japan’s new industrial and military power would not eradicate its ancient culture but support and protect it. Being modern and Western in style was desirable and seen as a sign of cultivation and means. Novelist Émile Zola described the Parisian department store as “the cathedral of modern commerce, solid and light, made for a nation of customers” in his 1883 novel Au Bonheur des Dames. It’s fair to say that for department stores in Japan, something similar was at work. According to scholar Younjung Oh, several protégés of Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835 –1901), a Meiji government adviser and the founder of Keio University, went on to work in key positions at some of Japan’s leading department stores, bringing their values to bear on the stores’ operations.1 Oh cites an apt description coined by scholar Louise Young, who described Japan’s hakurankai (industrial fairs) and kankoba (exhibition halls) as “missionaries of civilization.”2

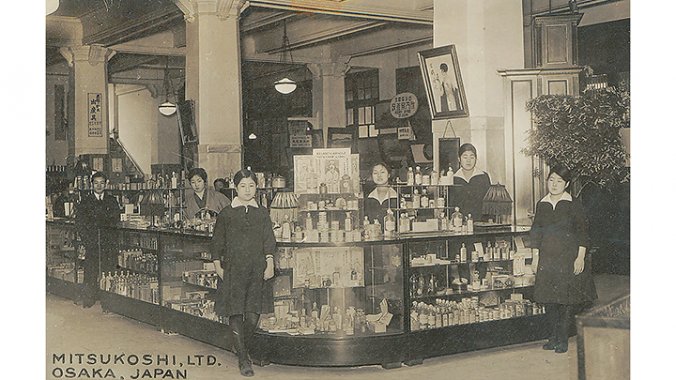

One of Japan’s oldest stores got a dose of American merchandising know-how thanks to the efforts of Yoshio Takahashi, who had studied with Fukuzawa Yukichi. Takahashi traveled to Philadelphia in the 1890s to study the displays and ambiance of Wanamakers, then one of the United States’ most successful department stores. Takahashi took over operations at Mitsui Gofukuten in 1895, which was renamed Mitsukoshi. He did away with the Edo-era requirement that customers personally request access to each piece of merchandise, and adopted Western-style stocked floor displays that encouraged visitors to browse. In 1904, Mitsukoshi took a full-page ad in a newspaper announcing its transformation from a gofukuten, traditional drapery shop, into a department store, coining the term depātoento sutoa, a variation on the English term. Department stores are still known in Japan today as depāto.3

Meiji-era Japan grappled with modernization and Westernization in multiple ways, and class differences informed the ways various strata of Japanese society confronted, and even embraced, the changes. Just as in the Edo era, when the newly prosperous merchant class partook of the aesthetic and sensory pleasures of their part of town, the yoshiwara, a new urban bourgeoisie, was taking its place in Japan’s large cities. They were called the Yamanotezoku, or Yamanote people; the Yamanote got their name from the train line that connected their neighborhood to downtown Tokyo at the turn of the 20th century.4 Just as in Western capitals, the advent of railway lines connected people in surrounding areas to the new department stores. The Yamanote bought things that Japan’s historic elite weren’t too concerned with. If a store like Mitsui still depended on the old guard for its trade in fine kimonos, the Yamanote were keen to buy goods ranging from fashionable clothing and accessories, stationery, and cosmetics to fine art as defined by Western standards.5

But department stores in Japan differed in an important way from their Western counterparts. They began displaying and selling fine art almost as soon as they opened their grand doors, and their Yamanote customer base viewed the purchase and display of works of fine art as a path to personal cultivation and betterment. The doctors, dentists, lawyers, bankers, and government officials who formed Japan’s new bourgeoise took the Meiji slogan Bunmei Kaika (“Civilization and Enlightenment”) to heart. There was even a taste-making periodical, Mitsukoshi House Magazine, which promoted the new look and feel of the goods for sale as symbols of progress, refinement, and “Mitsukoshi taste.”6

Mitsukoshi adopted the idea of “fine art” with enthusiasm, after the concept arrived from the West, according to Younjung Oh. The separate Western conceptual categories of fine art versus craft did not exist in Japan until they were imported during the Meiji period. Fine art was termed bijutsu (“beautiful technique”) and craft was translated as kôgei, a term that is still widely used to refer to fine craft in Japan today.7 The Tokyo School of Fine Art was founded in 1889 and the Imperial Museum the following year.

By the time the Mingei movement took shape in the 1920s and ‘30s, folk craft or traditional Japanese handicrafts were clearly being identified and celebrated as their own class of artistic endeavor. In 1904, Mitsukoshi hosted its first art exhibition. The subject was Edo-era painter Ogata Kōrin, whose work happened to be in a style from the Genroku era (1688 – 1704) that was having a resurgence. With this reference to Japanese art history, the exhibition reinforced the idea that their customers were discerning possessors of “Mitsukoshi taste.” In 1907, the store established an art department to display and sell the works of leading contemporary artists in Japan, including participants in the newly established Monbushō Bijutsu Tenrankai, or Ministry of Education Art Exhibition.8

In the early 1930s, Japanese department stores began hosting craft exhibitions. Just as fine art as a discrete category had to be imported from the West, so too the Japanese mingei movement was inspired by the British and American Arts and Crafts movement. Mingei, which many in the West associate with Japanese craft, specifically connotes the Mingei movement established in the 1920s by Yanagi Sōetsu, Hamada Shōji, and Kawai Kanjirō. The movement celebrated what its founders characterized as “the handcrafted art of ordinary people.” Mingei as a term can thus be understood as being akin to “Arts and Crafts” in that it connotes a specific historical movement. In 1932, Takashimaya presented a large exhibition of “new mingei” crafts from the San’in region of Japan. In 1934, the department store Matsuzakaya staged two exhibitions of ceramics. One featured work by Japanese potters Tomimoto Kenkichi, Kawai Kanjirō, and Hamada Shoji, as well as the British potter Bernard Leach. Another showcased thousands of pots made by anonymous artisans from all across Japan — these pots were characterized as the products of “folk kilns” or minyō. Mitsukoshi, Matsuzakaya, and Shirokiya in Tokyo, Hankyu in Osaka, and Daimaru in Kyoto all began to regularly feature mingei wares, usually on their upper floors intermingled with or adjacent to their housewares section.9

Depāto were also important sites for cultural cross-pollination. French designer Charlotte Perriand visited Japan in 1940 at the invitation of the Japanese Ministry of Commerce and Industry/Department of Trade Promotion to offer advice about increasing exports. She traveled for seven months throughout Japan, learning about its furniture traditions, and in 1941, she collaborated with Takashimaya to present an exhibition called “Tradition, Selection, Creation.” The show featured an array of Perriand’s recommendations for new designs, some Japanese designs she liked, and some of her own designs. She suggested adapting an Okinawan liquor ewer for use as a teapot and grouping it with lacquer bowls and tea cups on bamboo trays. She also recommended using traditional woven cedar bark and mino straw as upholstery material. She designed a version of her own chaise longue — the original version of which was made from steel and leather — in bamboo.10 In 1954, she worked with Takashimaya to organize a second exhibition called “Synthesis of the Arts,” this time with an emphasis on tableware.11 In the 1950s, the industrial designer Russel Wright traveled to Japan under the aegis of the American foreign aid program. He was there to promote the concept of “Asian modern” design; he advised the Japanese government on the promotion and export of handmade craft goods to the United States, and he was instrumental in the establishment of the Japanese Good Handcrafts Promotion Scheme.12

As Japan rebuilt from the devastation of the Second World War, demographic changes dramatically reshaped its society. During the 1950s and ’60s, the country’s “miracle decades,” there was substantial migration from the countryside into the cities, and this new, urban generation was the first in Japan’s history to lack a direct connection to rural life and traditions.13 During this period, as the country both embraced and created new technologies, department stores balanced their emphasis on progress and the latest fashions with nostalgia of a sort that could be understood as a form of culturally conservative noblesse oblige. Although Japan’s Edo-era Confucian social hierarchies are not as rigid as they once were, their values have left a mark on department store culture to this day. The pursuit of profit was not considered righteous in pre-industrial Japan, so a merchant ethic evolved to counterbalance the perception of crass commercialism with social responsibility. This ethic held that wealth brought with it great social responsibility. The turn-of-the-century depāto addressed this by presenting art exhibitions and educational offerings, and these continue to this day. According to scholar Millie Creighton, Japanese department stores hold exhibitions of all sorts. “On a visit to a department store in one of Japan’s urban centers,” she writes, “one might find an exhibition of folk instruments from around the world, textiles from India in the fabric department, utensils for the tea ceremony or exquisitely crafted miniature villages made of decorative sugar cubes in the food floor. There may be craftspeople engaged in demonstrations or musicians giving performances somewhere in the store.”14 Japan has relatively few public museums or galleries. To some extent, the cultural offerings of the depāto play a cultural role similar to that of a nonprofit art institution, and support the livelihoods of contemporary makers. Creighton notes that staff members in major department stores are expected to have broad cultural knowledge and to study the visual and performing arts as part of their training.15 Success for working artists and craftspeople in Japan can hinge on work being shown in a department store exhibition. In a way, department store museums are like the mirror image of the museum gift shop: you "enter through the gift shop," so to speak, in order to get into an exhibition, and not the other way around.

For the generations of Japanese people who have grown up in the decades since the end of World War II, in and around major cities, the presence of craft in department stores, both as cultural attraction and desired commodity, is a connection to tradition, both real and cultivated. Japan invested heavily in its craft traditions after the war, inaugurating its Preservers of Important Intangible Cultural Properties (better known as the Living National Treasure program) in 1950. Even as Japan modernized and boomed economically, it had been stripped of its military might in defeat and needed to project a new image of cultural power around the world. Crafts offered beauty, an abstract simplicity that dovetailed beautifully with postwar modernism, and a sense of connection – both real and romanticized – to Japan’s pre-industrial past.

A visit to the flagship Takashimaya in Tokyo’s Nihonbashi neighborhood in the spring of 2018 suggests that the handmade and traditional are very much an ongoing concern. On the seventh floor, a large area is devoted to the display and sale of silk kimonos. There are fitting rooms and expert staff, mostly women, waiting to help customers choose from a dizzying array of fabrics. Near the European and American china and silver, which is marketed to newlyweds just as it is in the West, there are handmade wooden serving dishes and bowls, wood-fired ceramic tea bowls, and handwoven baskets. In fact, during my visit, there was a craftsman demonstrating how he makes his baskets, right in the middle of the luxury tableware display, just as Millie Creighton described. Nearby, at the craft and hobby mecca Tokyu Hands, entire floors are dedicated to wood and woodworking tools, stationery and origami paper, fabric and sewing supplies, pens, paints, inks and brushes – so much so that the store’s motto (which sounds a little unusual translated into English), “A Creative Life Store,” makes perfect sense.

Japan’s department stores both are and are not like those in the West. In Victorian-era Europe and North America, museums were civilizing destinations where middle-class families could seamlessly experience leisure and culture simultaneously. In Japan, the Meiji ideal of seeking “Civilization and Enlightenment” shaped the depāto into businesses where the Western custom of no-strings-attached browsing became a way for Japanese citizens to support, admire, and celebrate the country’s art, design, and traditional crafts in the 21st century.

Read more from the fourth issue purchase issue

1. Younjung Oh, “Art into Everyday Life: Department Stores as Purveyors of Culture in Modern Japan,” PhD dissertation, University of Southern California, May 2012, 342-343.

2. Louise Young, “Marketing the Modern: Department Stores, Consumer Culture, and the New Middle Class in Interwar Japan,” International Labor and Working-Class History, no. 55 (Spring 1999), 56; cited in Oh, 2012.

3. Brian Moeran. “The Birth of the Japanese Department Store,” in Asian Department Stores, edited by Kerrie Macpherson, 141-176. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press, 1998, 145-146.

4. Ibid, 152.

5. Younjung Oh, 2014. “Shopping for Art: The New Middle Class’ Art Consumption in Modern Japanese Department Stores,” Journal of Design History, 27 (4), 2014, 353.

6. Julia Sapin, “Liaisons Between Painters and Department Stores: Merchandising Art and Identity in Meiji Japan, 1868-1912,” PhD dissertation, University of Washington, 2003, 81.

7. For more on the terminology of crafts in Japan, see Yuko Kikuchi, Japanese Modernisation and Mingei Theory, Cultural Nationalism and Oriental Orientalism, London: Routledge, 2004, 237-8.

8. Oh, 2012, 19.

9. Kim Brandt, Kingdom of Beauty: Mingei and the Politics of Folk Art in Imperial Japan. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007, 104.

10. Kikuchi, 2004, pp. 120-121.

11. Mary McLeod, Charlotte Perriand: An Art of Living, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2003.

12. Yuko Kikuchi, “Russel Wright and Japan: Bridging Japonisme and Good Design through Craft,” The Journal of Modern Craft, Volume 1, 2008, Issue 3, 357-382.

13. Ueno Chizuko, “Seibu Department Store and Image Marketing: Japanese Consumerism in the Postwar Period,” in Asian Department Stores, edited by Kerrie Macpherson, 141-176. Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, 1998, 182

14. Millie Creighton, “Something More: Japanese Department Stores’ Marketing of a ‘Meaningful Human Life,’” in Asian Department Stores, 209.

15. Ibid, 210.