If the Shoe Fits

From American Craft Inquiry: Volume 2, Issue 2

History can be traced through the objects that surround us. Shoes, as objects both intimate to the body and subject to the natural environment, allow us to trace cultural, technological, and social change, as well as to track developmental changes in the human body itself. With one of the world’s largest shoe collections, Toronto’s Bata Shoe Museum is perfectly poised to explore the multiple meanings of these intimate objects; one only needs a guide in reading the collection.

Elizabeth Semmelhack, senior curator at the Bata Shoe Museum, explores these histories – of making, buying, desire, and fulfillment – as she walked me through the collection recently and explained her role in its use and growth, as well as the unique position of the museum as a cultural institution and historical archive.

Amara Hark-Weber: Can you talk about your role at the museum and how you came to take over this unusual collection?

Elizabeth Semmelhack: I took a winding road to get here. I went to Bennington College, where I studied painting, printmaking, and Japanese literature. After graduation, I did research and education at the IBM Gallery of Science in New York, which focuses on high-caliber, smaller exhibitions. Working simultaneously in research and education fostered an interest in art history, so my next step was to earn a master’s degree in Western art history at Tufts University, with a focus on Japanese print culture. During that time, I realized that I wasn’t interested in unique works of art created to be consumed by an individual but rather in objects that had been mass-produced. In many ways, it’s easy to see how my interest in 18th-century Japanese prints fed into what I do now. Footwear, like Japanese prints, is not designed to be an eternal expression of a platonic ideal. Rather, it is created to meet the desires of a moment. I am still deeply interested in the ways in which culture both creates and fulfills our material needs. You can see this call and response by looking at consumables, particularly mass consumables.

After this, I began working at the St. Louis Art Museum, which was fantastic in many ways, but I happened across a job description for the Bata Shoe Museum that looked quite interesting. I quickly realized that my background in Asian and Western art history, as well as my experience working with indigenous materials from North America, all fit naturally into what would become my role here as senior curator. I was already comfortable researching and curating exhibitions surrounding the cultures that the shoes in the Bata collection represented. I also realized that working here would allow me to continue my research into the intersections of gender, fashion, and economics, as well as to accomplish a lot of firsts. So, I took the job and have been here ever since.

Can you discuss the archive here – the curatorial process and how the collection has grown? Do you approach it as both history of culture and history of making?

Of course – there are multiple stories embedded in each individual artifact. To talk about the collection more generally, in many ways, we are a singular institution. Mrs. Sonja Bata began collecting footwear in 1949, and by the 1980s, she had acquired more than 7,000 pairs of shoes. At that time, it was suggested that she open a museum dedicated to the history of footwear. In many ways, the collection itself is an artifact of Mrs. Bata’s collecting style, which shifted over the years. Because of this, the museum developed organically, without rigid expectations as to what the collection should include.

Mrs. Bata had an incredible eye and was very curious about footwear from around the world. We have excellent and beautiful examples that span geography and time periods. But we still only – though that word sounds a little ridiculous in this context – have 13,000 artifacts, so there is room to expand. I think that one of the challenges we will face now that Mrs. Bata has passed will be the establishment of parameters for our collecting in the future. I would like to emphasize footwear that has had global importance or been part of a global moment. For example, I think that we need to get a pair of men’s slides.

Funny you should mention slides. I just overheard a conversation in the airport about slides.

Yes, they are ubiquitous right now – a little intimate, a little revealing. It’s an interesting artifact and a moment that I think should be represented in the collection.

How would you describe Mrs. Bata’s style of collecting?

She collected in a variety of ways, from acquiring at auction houses to funded research trips. She also developed very good relationships with a number of important dealers who kept their eyes out for unusual pieces. Frequently, however, her collecting was exhibition-focused. For example, before I arrived, she mounted an exhibition on the traditional footwear of India, which greatly enriched our Indian holdings. She did the same with an exhibition on Han Chinese footwear. She would take these as opportunities to grow the collection as her knowledge of a certain area or culture deepened.

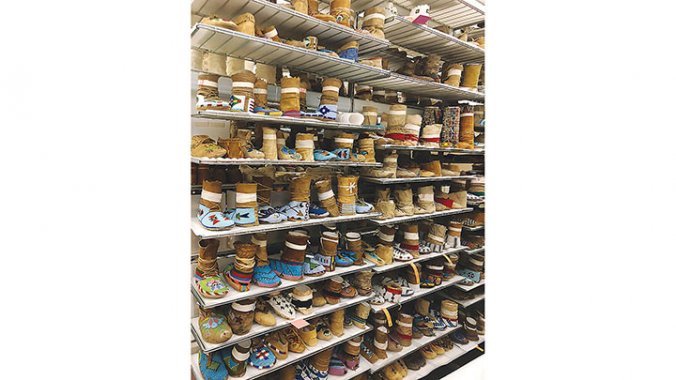

Mrs. Bata also had specific interests – she really loved 18th-century materials and also admired North American moccasins, so our holdings in these areas are particularly strong. She sent researchers to all the circumpolar countries to talk to women making traditional footwear. That field research resulted in us collecting not only the footwear, but also the skins, the tools, and, importantly, the stories about who made what, why they made it, and for whom. As a result, we currently have the largest collections of indigenous and circumpolar footwear in the world, something in which the museum takes great pride.

It sounds as if the collection grew largely with specific goals in mind. Do you also receive donations?

We do get donations, and I learned early in my tenure that what is found in people’s closets or attics can be very important. This was really driven home to me once when, in the middle of an install, a woman came in without an appointment. I was a little impatient, but I agreed to meet with her. As it turned out, she owned an amazing pair of shoes from World War II that her American boyfriend, stationed in France, had purchased for her. Not only did the shoes have a fascinating story, they were also beautiful. I realized at that moment that I have to remain open. You just never know what people might bring in.

Would you say that the museum is more focused on the stories surrounding the object or on the objects themselves?

Both. We are definitely as interested in the story of how a pair of shoes gets used as in how and for what purpose it was made. When I was at the St. Louis Art Museum, every day when I went to get my coffee I walked by this one Van Gogh painting. I would stand in front of it – about an arm’s length away – and say to myself, I’m standing as far from this painting as Van Gogh did when he painted it. I would think about him, the maker, think about what was he doing, wonder what he was thinking. Was he looking out a window? What was going on around him? It was all about the maker. I never thought about who had bought the painting or its journey to St. Louis. I was trained to focus solely on the maker. However, when I arrived here, I would hold a shoe in my hand and I couldn’t help but think about the wearer. With shoes, both the object and the story surrounding it are so clearly embedded, and this dual nature is unusual. It allows us so many vantage points through which to look in and look out.

I always think of shoes as having dual lives. As a shoemaker, I have an incredibly intimate relationship with the object as I’m building it, and when I finish, standing back and looking at it, I think, “This is my object.” I feel so connected to it. But as soon as the client puts it on, animating it, there is an entirely new meaning. It’s no longer mine at all. It separates from me and starts a second life reflecting the wearer – their body, their gait, where they go, how they move.

Yes, shoes transform their wearers, and wearers transform their shoes.

Exactly. It’s a beautiful and fascinating relationship, and the shoe is an unusual object in that nature. I also find it interesting that the museum emphasizes both parts of this cycle of footwear making and wearing.

I agree. I also think that one of the things that makes footwear interesting from a museum standpoint is that other articles of dress collapse without the body: a dress off the body is just a pile of textiles. Shoes, however, retain the shape of the wearer, they show footprints and wear patterns, allowing you to truly imagine the person who stood in them. There’s something unique about it. It allows the viewer to connect with the past in an incredibly intimate way.

I had this experience myself with a pair of 1770s moccasins from the collection. I grew up in upstate New York, and as a kid was interested in the American Revolution and where it had been fought around the state. We have a pair of Mohawk moccasins in the collection – one of my favorites – [that] were worn in that time and place. They were made by a singular woman for an individual man, both of whom likely lived through, or around, the time of the Revolution. The fact that you can see the man’s footprint so clearly when you flip them over makes that history very human.

I love these stories. I started thinking of this dual nature of shoes last fall l when I visited the V&A [Victoria & Albert Museum, London] archive last fall. There you have two hours to view four pairs of shoes, not touching, just looking. At first, they were just objects, but as I sat there, they started to transform. It was like watching origami unfolding to reveal secret messages— split seams, wear patterns, structural elements being exposed because of misfit, tiny mending stitches in the cloth. They were the stories of the wearer. But there were also all of these marks of the maker’s hands – irregularities in the curves, the way that beading was placed. They were the same things that I sweat over in the workshop, and were just as much a part of the story as the wear patterns. Seeing them made me feel as if I were a part of a larger and longer story of shoemakers, a narrative that I am so embedded in that I rarely see it. But back to the Bata archive. How is it used by the public?

We get many researchers coming through for a wide range of reasons – some for design inspiration, some for deeper historical research. We try to be as open as we can to visitors, bearing in mind that we have a very small staff.

Can you think of any examples of how research done in the archive has been used for a specific project or product?

One interesting project was a company that came through recently to look at hide use among the Inuit in an effort to make its own products as environmentally sustainable as possible. I don’t know if the project will come to fruition, but the questions they were asking were really quite interesting.

You mentioned your research into gender earlier. Collections like this one are frequently gendered. Footwear is gendered, apparel is gendered, the making process is gendered. Could you talk about gender in terms of your collection, and also footwear more generally?

Of course. Gender is central to my research, and the collection is an incredible palette from which to draw. I started working here at the height of the “power” high heel, that time when the term “shoe-aholic” came into use to refer to women and their footwear collecting. There was this idea that women were somehow biologically driven to acquire footwear. Even the term “shoe” was becoming feminized. I would be at a party and someone would find out what I do and automatically assume that the museum was geared toward women. I found this fascinating, especially because we don’t live in a culture in which men go barefoot and only women wear shoes. Why does “shoe” instantly conjure a high heel? Why is the word “shoe" equated with femininity?

So I began working on the history of the high heel. One of the first things my research revealed was that heels were originally created for men, probably in relationship to the stirrup. I traced them back to 10th-century Persia. In my research I argue that men wore the first heels in Europe and that women only adopted the high heel during a brief trend during the early 1600s when they were trying to masculinize their appearance. All of these things went counter to the narrative that we had all swallowed hook, line, and sinker. I also questioned why we don’t see cowboys as wearing high heels, even though they clearly have elevated heels on their boots. Instead, these heels are seen as incredibly masculine, even though they are one of the few places in Western culture where a 2½-inch heel heightens one’s masculinity.

Around this time, I also decided to work on sneaker culture because there are many men for whom collecting, wearing, and buying sneakers is central to their identity and construction of masculinity. This was happening simultaneously with the idea that women were predisposed to buying shoes, but somehow sneaker culture and sneaker collectors were not considered the same kind of shoe-aholics. In response to this, I wrote the book and put together the sneaker exhibition “Out of the Box: The Rise of Sneaker Culture.” These questions about gender and consumption have been central to my work since I started here at the Bata.

One of the things that I’ve noticed about gender in shoemaking is that 80 percent of my students are women, but 80 percent of my peers are men. I also know there is a long history of women’s involvement in shoemaking. Could you talk about that?

Absolutely. Women have long been central to shoemaking. When shoemaking was workshop based, women – including wives, daughters, and others – were essential to binding uppers, embroidering, and doing the more “delicate” work of shoemaking. Industrialization in the 19th century fractured workshop shoemaking. After this, women were employed to do piecework, that is, sewing uppers at home. The invention of the sewing machine actually increased women’s involvement in shoemaking by bringing them into factory settings. The more physical work of lasting, putting on soles, etc., however, remained male. Somehow this gendered work split persists. In contrast to the West, there are many cultures in which shoemaking is completely female. For example, throughout the circumpolar regions the making of footwear is traditionally female. In certain parts of China it was female. In Native North America it was always female. What is most interesting and important to me is that it’s always gendered. In some ways industrialization challenged that in the West because it allowed women, independent of any connection to shoemakers, into the process. It brought them into a factory system where they worked alongside men, albeit doing different jobs. Overall, however, within Western culture, it still reads as a masculine occupation.

That’s one of the things that I’ve noticed when visiting factories in the United States, and even more so in Europe. There, all the upper makers are women and nearly everyone else is men. But challenging so many aspects of these systems are the cowboy bootmakers. One of my favorite memories of going to the Boot and Saddlemakers’ Roundup, in Wichita Falls, Texas, is seeing all these male bootmakers, everyone wearing high-heeled boots with incredibly colorful embellishments.

And really pointy toes!

Yes – just incredible work – but they were all talking about their sewing machines. To my eyes, it was unmistakably masculine, but taken out of context, every cultural signifier was distinctly feminine.

That really demonstrates how these ideas are socially constructed. In my most recent book, Shoes: The Meaning of Style, I write about female collecting and male collecting. Both men and women are interested in having many pairs of shoes in their personal collections, yet women’s collecting is posited as emotional: “I couldn’t help myself,” “I just had to have another pair,” “Oh, it’s ridiculous that I’m spending all this money on shoes,” whereas men’s collecting is positioned as being more rational. For example, when Air Jordans came out, first there was the Air Jordan, then Air Jordan II, then III, then IV. It played into traditionally male ways of collecting, so that if you have I and II, then it’s only logical to acquire III. If you skip to the VI, your collection is missing the IV and V. One could argue that this style of collecting is rational, reasonable, and an investment, yet the Air Jordan collector may still end up with the same number of shoes in the closet. With these two modalities of collecting, one is denigrated as indulgent and a result of lack of control and the other is seen as rational and reasonable. It’s incredibly interesting that this is seen as so different when the collection has the same number of shoes.

In terms of the Bata collection, do you try to represent different or unusual construction techniques, or is it based more on style, story, and culture?

Understanding footwear construction is central to our work, and this is especially true with our circumpolar collections. That said, Mrs. Bata did have a fondness for particular styles and time periods.

There is probably more evidence of upper-class footwear, as those shoes weren’t worn as hard.

That is true. Upper-class footwear gets saved, and lower-class footwear gets worn out and discarded. A really interesting example of work shoes that largely didn’t survive is slave shoes. They were actually one of the principal ways that New England shoemakers made their money prior to the Civil War. There was a very symbiotic economic relationship between North and South, but slave shoes produced for the South were never saved.

Are there records of slave footwear or other working people’s footwear if the objects themselves didn’t make it?

There are some records, as well as published negotiations between the North and the South. Once the Civil War broke out, the North had the advantage of being able to shoe its armies. In the South it was a different story, making slaves with shoemaking skills incredibly valuable but extremely rare. The expression, “You need boots to win the war” was literally true at that time.

To shift slightly, does the Bata collection interface with other collections?

We lend to other institutions, and I have consulted with many shoe collectors. Additionally, we answer questions from institutions regarding their collections all the time. There are other shoe museums in the world, and many collections within larger institutions. The two that are most similar to us are the Northampton Shoe Museum and Art Gallery in England, and the Musée International de la Chaussure in Romans-sur-Isère, France. Both have wonderful collections but differ from us in that they focus more on local footwear production. Northampton was the center of shoemaking in England and Romans-sur-Isère was the center in France.

We are more focused on the history and culture surrounding the shoes in our collection.

Beyond the shoes themselves, do you also collect shoemaking tools or other objects related to the trade?

Yes, we collect everything related to shoes, and from many different cultures. Our holdings range from socks to statues to buckles, as well as the tools used to make the objects in the collection.

Wow. So when you are holding exhibitions, do you include the making side of things?

Yes, frequently we do. We recently held an exhibition called “Fashion Victims: The Pleasures and Perils of Dress in the 19th-Century,” which looked at 19th-century fashion production and consumption and questioned who the victims were. One section specifically looked at the shifts in shoemaking across the century. It began with traditional workshops and the many injuries that occurred among shoemakers. It then talked about industrialization and the fact that shoemakers were largely unemployed by the end of the century, being forced to move from master craftsmen to cobblers. This section included a shoemaker’s bench and tools, as well as women’s piecework, the introduction of the sewing machine, and a discussion of industrialization. Because we have multiple examples of these artifacts in our collection, we were able to create a very rich story, one that most people don’t think about.

It sounds like the museum is trying to answer questions for the viewers that the viewers didn’t even know they had.

Hopefully.

Are there questions that you hope to spark in people?

I hope to encourage people to think more broadly and to ask the question, “Why?” For example, when we chose the title “Fashion Victims” for the 19th-century exhibit, which I co-curated with Alison Matthews David, we really wanted to challenge the blame-the-victim implications of that phrase by showing 19th-century footwear production and consumption in a more complex way. Of course, we wanted to consider the narrow shoes and “straights” that were so popular during the century. But we also wanted to ask why these fashions were so prevalent. Who was benefiting? Who was being harmed? We tried to be as thoughtful and curious as we could to challenge accepted storylines and boundaries.

What are some examples of technology and invention from that period that are linked to footwear development?

I think that in terms of manufacturing capability and what fashion was willing to do, a really good example is straights. After the turn of the 18th-century, high heels were totally out of fashion. The value of high heels prior to that was that they hid the bulk of the foot under the skirt, which was in keeping with concepts of idealized femininity through diminutive feet. Having extremely tight, narrow shoes is another way to show a delicate foot. It is then taken a step further by creating shoes in straight form instead of rights and lefts, because they heighten this visual effect. Also, they can be made more cheaply. If you aren’t doing a right and left, a workshop can really turn them out. They didn’t even need to make pairs; they could just make singles that could later be paired by someone else and then boxed and sent off. This perfect storm of shifts in nascent industrialization and changes in idealized femininity allowed for a totally new shape of shoe.

For those who are not familiar, what is a straight?

A straight is neither right nor left, it’s straight. Some people think that lefts and rights were only invented in the second half of the 19th-century, when left and right came back into fashion. That’s not true. Rather, the creation of straights is directly related to early industrialization – a synergism between industrialism and fashion that created the look of very symmetric feet.

To me, some of the misunderstandings about shoes is that they are frivolous, sometimes harmful, almost always disposable, and today stand in as contemporary icons of consumerism. This archive and museum argue that the shoe is central to human culture and history, and that it can act as a prism through which to view ourselves today as well as our past. How do you talk about this juxtaposition?

I think that the best way to figure out the cultural moment you’re in is to look critically at the things that feel most natural. This is how I began working on the history of the high heel. When I was first hired, the museum was doing an exhibition on Chinese foot-binding. People were incredibly curious about this practice and many asked pressing questions, questions that were not being asked about high heels – an equally odd form of footwear. However, no one was asking why high heels were being worn in Western culture, and why only half of us wear them. The messaging around the high heel was so universally understood that no one even questioned it. Women wear high heels, full stop. Yet, as I stated before, my research has shown the actual history of the high heel is varied, and how it has come to be a signifier of hyper-sexualized femininity has nothing to do with the natural order of things.

The cultural meanings embedded in footwear are fascinating, but frequently left unexamined until after history or culture has changed. For example, if you see someone in a pair of Birkenstocks and automatically make assumptions about their dietary practices and political views, it suggests to me that footwear is doing a lot more work than just protecting the foot. We all read these messages so thoughtlessly, but they are all incredible cultural signifiers. Shoes offer us a surprising way of entering culture.

Can you tie that back into the importance of the Bata archive?

Yes! I think that what’s wonderful about the Bata collection is that it’s so wide-ranging. I’m not such a strong believer in “high art” or “low art.” The fact is that everything in our collection was made by someone to be used. So, if everything has some kind of utility, the question becomes what exactly that utility is. If you look at a pair of shoes for bound feet – shoes that women made for themselves – there’s a lot of cultural information wrapped up in every stitch. If you knew this and knew that footwear was one of the principal things that women made but didn’t have actual examples to study, all that information, those lives and skills and stories, would be completely lost to the historical record. That maybe is an extreme example, but I think that footwear has an overlooked yet essential job to do, ranging from protecting our feet to protecting our social identity. Because of this, studying footwear really allows for some of the nuanced complexity of human culture and human nature to be explored and considered.

Read more from the fourth issue purchase issue