A New Model for Craft Makers—Brought on by Instagram

Portland, Maine–based potter Ayumie Horie. Photo by Yoon S Byun. This photo is part of the @EmersonCollective's #AmericaSeen series.

Social media has altered the way craft artists conduct business and build communities since its invention, and with recent updates to the app, there's even more growing and learning to do as small business makers look to find new ways to market their work. Platforms like Instagram give makers an outlet to personalize their online presence. It's helped some makers achieve incredible success, and yet it's not without serious pain points for users. Art critic, writer, and museum scholar Seph Rodney asks five makers about their opinions and experiences running their small businesses through Instagram. Hear some of the benefits and setbacks this highly influential platform provides for its' creative and entrepreneurial users.

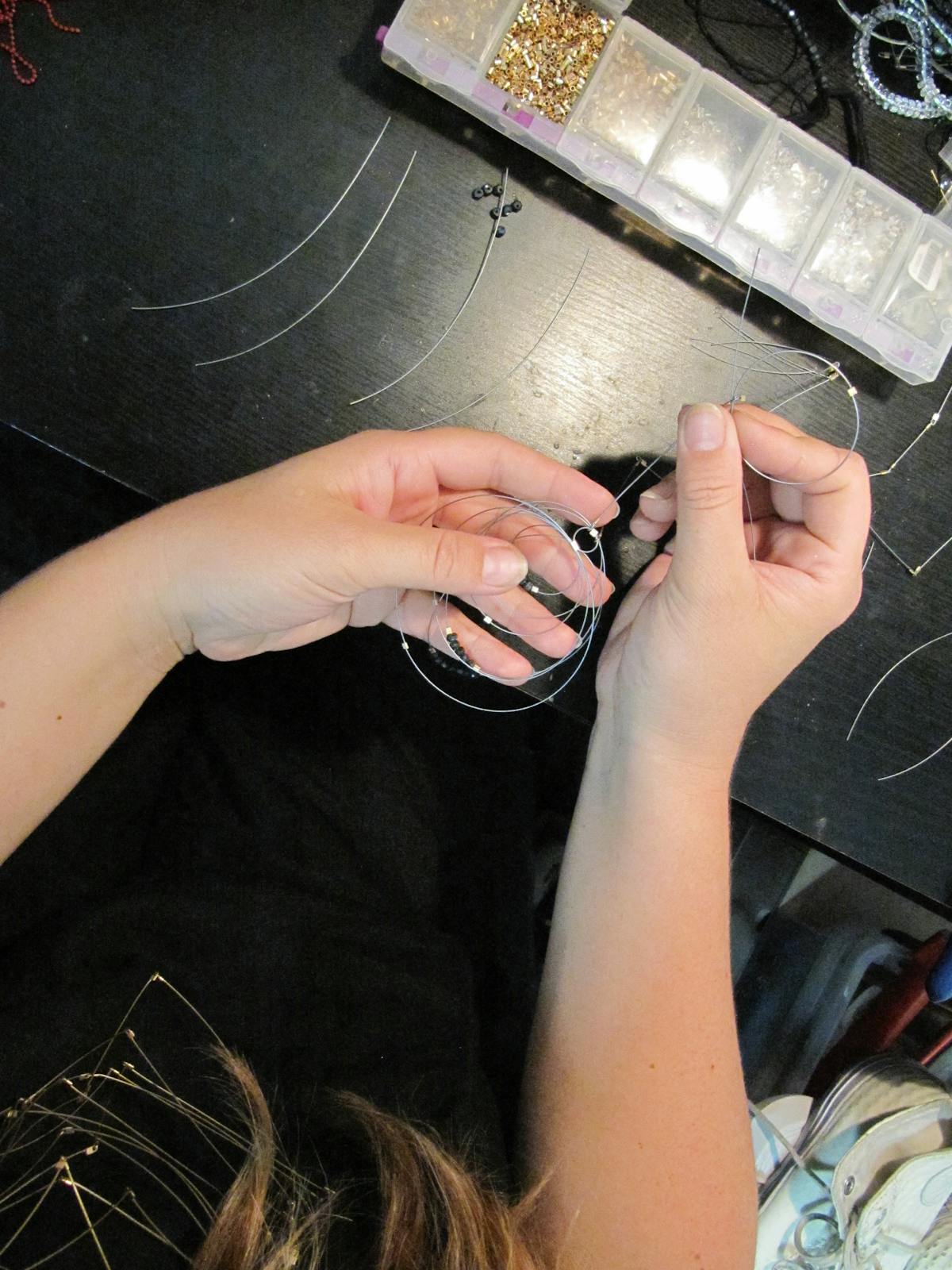

ABOVE: Seattle-based jewelry maker Twyla Dill in her studio with metal tools and spools of thread. Photo by Jess Griffin. LEFT: Dill crocheting lace. Photo by Celina Dill.

It is not hyperbole to say that Instagram has had a game-changing influence on craft by making it possible for makers who had previously had only niche audiences to become, in essence, independent small businesses and craft stars with throngs of followers. The Instagram “Live” and “Story” features have been instrumental in this development.

Currently, one of the app's most popular features is "Instagram Stories," which lets users post photos, images, or short videos that are viewable by others for 24 hours. Reportedly, about 500 million people used Instagram Stories every day in 2020, and over 2 billion users are active on the app every month. Because of the brief time limitation on these video clips, they are not ideal for craft makers who want to detail their methods and inspirations, but they are great for creating marketing teasers that entice viewers with a sampling of their inventions. For example, when Twyla Dill, a Seattle-based jewelry maker, recently wanted to alert followers that a line of earrings consisting of raspberry crocheted fabric over gold had been restocked, or that another line of hand-dyed pieces was running out, she used the Stories tool.

Other craft artists use the much longer-duration “Live” feature, which can host video for up to four hours, to talk viewers through their process and find out what resonates with them. Meghan Patrice Riley, a Brooklyn-based jewelry maker who was an early adopter of Instagram, says the dialogue with her audience helps her in her work. She says she loves using the IG Live feature and has developed a conversation series that is now integral to her process. “It helps me refine what I’m trying to show people and how to explain what I’m doing. Even if it’s not done, or fully thought out, it helps me start refining; it helps me gauge response.” Riley maintains that she has produced more-focused collections because the process of talking about what she wants to do helps her realize what is feasible, what her audience responds well to, and what she enjoys envisioning.

LEFT: Brooklyn-based jewelry maker Meghan Patrice Riley wearing her Shape Bib Necklace, 2021, 14k gold fill tubing and magnet clasp with nylon-coated, stainless steel cable. Photo by Meghan Patrice Riley. RIGHT: Meghan Patrice Riley in the studio. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The Instagram visitor who uses the site to discover craft artists who make pieces they’re interested in can search by the names of specific makers; by the general subject, such as “jewelry design”; or by more specific terms such as “bracelet,” “necklace,” “gemstone,” “bead,” or “sapphire.” This search feature allows for rapid detection of all kinds of craft and makers as well as patrons who have similar interests. Followers build ad hoc communities around these shared pursuits. And for artists, Instagram has changed the way they work.

Connecting Directly with Buyers

Given the scale of viewership and levels of interaction with artists posting on Instagram, the platform has essentially generated a new, hybrid model for the commerce of craft. Now these makers have the option of becoming more than just small business owners. They can essentially create their own self-contained marketing and branding operations. This has occurred because Instagram allows artists to circumvent the gallery system to find and attract customers and collectors—who, given the conditions of widespread social lockdown in the past two years, have flocked to Instagram to look for unique craftwork. As Ayumi Horie, a potter based in Portland, Maine, who has been active on Instagram for eight years, says: “As a business tool it’s really integral at this point. It cuts out the middleman so you basically double your income if you’re efficient at handling all the tasks that the gallery would normally do for you.”

+down+to+dimension+on+178kg+power+hammer.(2022)+Photo+Micheal+France.jpeg?fit=max&w=1200&auto=compress&cs=srgb)

LEFT: This kitchen set by Knoxville, Tennessee–based artist John Phillips features carbon steel damascus clad over 52100 steel, mokume-gane bolsters, and cocobolo handles—with a cocobolo display with handmade hardware. Photo by John Phillips. RIGHT: Phillips working a piece of damascus steel (1,850 degrees) down to dimension using a 178 kilogram power hammer. Photo by Micheal France.

The benefits are, as Horie alludes to, an expanded audience and greater revenue for the maker who markets their work through Instagram because a gallery isn’t taking a 50 percent fee, and the platform is free for posters and viewers. As John Phillips, a knife maker based in Knoxville, Tennessee, who has been using Instagram for about six years, explains, an IG handle has taken the place of other pre-digital marketing tools: “It’s a really easy way to have a business card. If you meet somebody in real life you can say, ‘Here’s my Instagram’; and they can look at that and get an idea of what your personal brand is.”

More importantly for Twyla Dill, viewers who are initially interested in her metal and crocheted lace pieces are able to get closer to her via the dialogue created through post comments and direct messages. Ultimately this intimacy facilitates the move from viewer to customer or patron. “People feel like they know you, which makes them feel connected to your work,” says Dill. “Customers who feel that they know me better feel better about purchasing, feel more connected to the work, which means they’re willing to spend more money, because they value what I do and the fact that I’m a human being.”

The Challenges for Artists

However, a sentiment I found echoed throughout the craft community that utilizes Instagram is that along with the benefits of this expanded, entrepreneurial agency there are also drawbacks. I spoke with several craft makers about their experiences using Instagram and found that, as much as they valued the ability to create and shape their own brands, they also were concerned about becoming too thirsty for audience “likes” and thus getting trapped in, as Horie call it, “monotonous loops of making.”

Portland, Maine–based potter Ayumie Horie. Photo by Yoon S Byun. This photo is part of the @EmersonCollective's #AmericaSeen series.

The concern among artisans is that they will take fewer risks and spend less time developing ideas and instead spend more time on the business of getting products out to customers. Phillips admits this: “You can connect to the audience too well, and next thing you know, you have too many orders.” (In fact, as of this writing, Phillips’ IG page indicates he is currently accepting no new orders.)

Mitchell Spain, an artist based in Norwalk, Iowa, who makes ceramics that resemble old, rusted canisters and other nostalgic items, admits to worrying that if he decides to step away from interacting with customers and patrons, he will pay a price. “It’s hard to disconnect from it as a business . . . . You’re worried that Instagram’s algorithms are going to cut you off if you don’t engage and you’re not active.” Spain, too, is alert to the problem of making work for likes. “All the time it takes to manage your social media, that’s taking away from your studio time, from doing the actual work.” And there is a meaningful difference between an Instagram presentation, with its filters and editing tools, and the actual thing that is made. As Phillips reminds me, sometimes “Brands don’t reflect high craft.”

So another worry among these artists is that maintaining or burnishing their online image will take away from doing the actual work of making. On the other hand, Riley admits that the pressure to show up forces her to make and hold boundaries so that she doesn’t get sucked into a vortex of working for her audience instead of for herself. It seems that, depending on the kind of craft artist you are, the tasks and tests will be different, but the maintenance of boundaries is crucial.

LEFT: Norwalk, Iowa–based artist Mitchell Spain in his studio. Photo courtesy of the artist. RIGHT: Mitchell Spain, Assorted Mugs, 2020, porcelain, ceramic decals, lustre, 3 x 4 x 5 in. each. Photo by Mitchell Spain.

Another borderline these artists have to carefully watch is the divide between their own ideas and methods, found after long hours of practice and experimentation, and those of other Instagram users who may appropriate similar ways of making. Innovative craft makers have to keep careful watch that their work or processes aren’t being stolen by others who will blithely take what they find on Instagram and use it to promote their own brands, particularly if the appropriator has a larger following. As Spain explains, “If you create a certain process, then someone else can start using that process . . . and that’s harder to fight.” Therefore, craft artists have to do two somewhat contrary things at the same time: open their methods and techniques to wider audiences, while also watching out that they are not being exploited by other craft makers.

New Potentials, New Work to Do

In all these possibilities, new communities have emerged on the platform due to artisans wanting to share their work, processes, impediments, and concerns with like-minded makers. For example, last year Horie organized a “Sexism in Ceramics” panel discussion with Sunshine Cobb to create a forum for women working in craft who have to deal with issues of sexism and discrimination. The panel aided these artists by talking about resources that offer gender-specific support, and included a presentation by attorney Dana Lossia about the use of nondisclosure and non-disparagement agreements. Horie’s panel was associated with ad hoc groups loosely organized on the platform by collectives such as #feministceramics and #feministcraft. These groups bring people together and mobilize their work to protect and nurture artists in their created community. As in the corporeal world, issues of identity, agency, and power are unifying elements that bring people into conversation with each other.

Ultimately, Instagram is a meeting place of contradictory impulses. It may be commodifying craft even as it makes it instantly and ubiquitously visible. But because of the ad hoc communities that rise out of video meetings and hashtagged movements, the app is also a place that could potentially foment social change. As John Phillips claims, “It doesn’t have to be this solely capitalistic platform for advancement.”

In this new digital paradigm, craft artists are faced with many choices, more choices than were available before Instagram came to be. They can take the route to becoming full-on Instagram influencers with thousands of followers (global spending on this kind of marketing is predicted to be worth $15 billion sometime this year); they can be profitable small-business owners with all the watchfulness and devotion to clients that that entails; they can nurture their own practice and keep pushing themselves to innovate; and/or they can connect to a craft community around them and look to issues of equity to expand opportunities for other artists. In the final analysis Instagram implicitly asks craft artists who they want to be while offering them opportunities to enact that identity in the world.

Seph Rodney, PhD, is a former senior critic and opinion editor for Hyperallergic and has written for the New York Times, CNN, MSNBC, and other publications. His book The Personalization of the Museum Visit was published by Routledge in 2019. In 2020 he won the Rabkin Arts Journalism Prize. Portrait by Tyler Andrew.

Discover More Insightful Articles in Our Magazine

Become a member to get a subscription to American Craft magazine and experience the work of artists who are defining the craft movement today.