The Queue: Arleene Correa Valencia

The Queue: Arleene Correa Valencia

Arleene Correa Valencia’s poignant works illuminate the pain of migrant family separation.

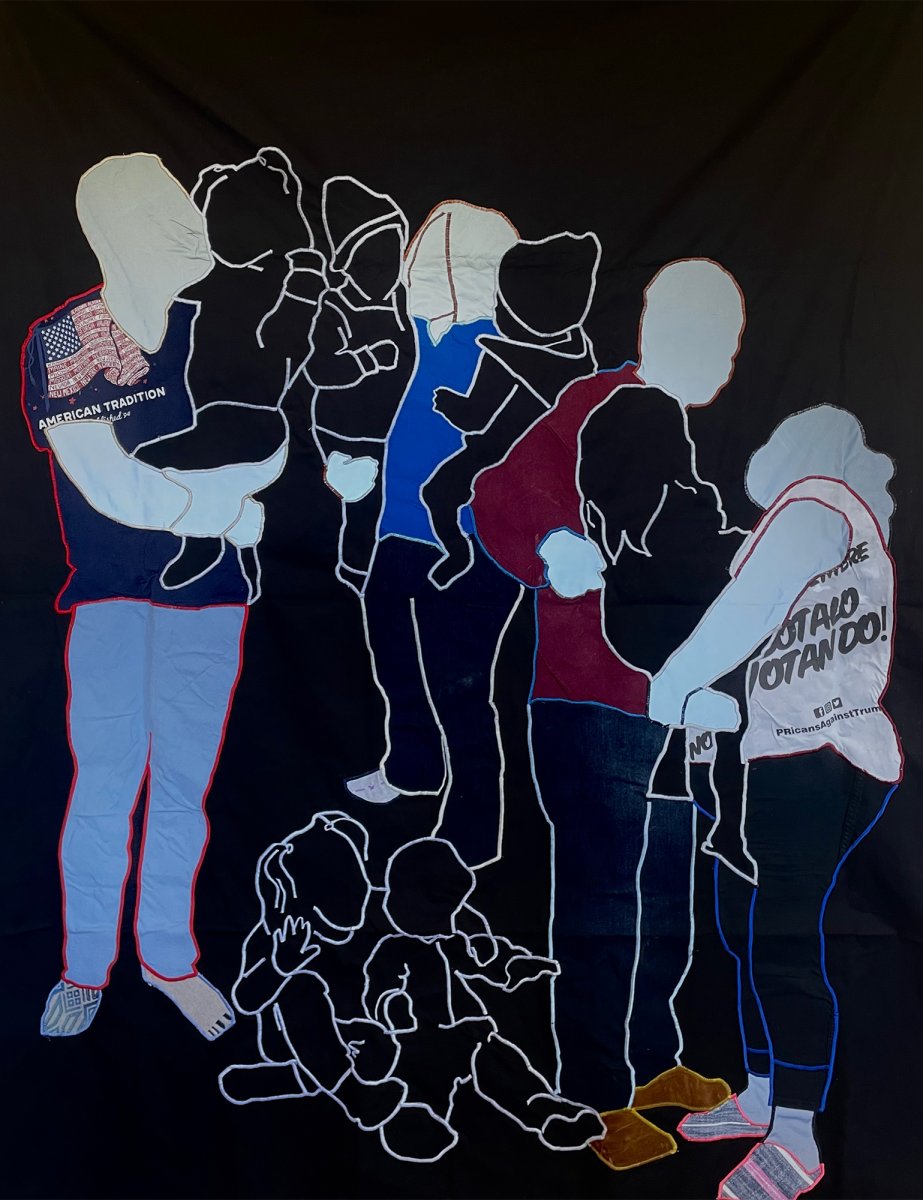

Faceless figures draped in American flags, high-visibility yellow vests, and cascading Mexican embroidery populate Arleene Correa Valencia’s paintings, textiles, and sculptures. Pain, yearning, and love are evident in the people she depicts in her work, who cluster together and hold each other tightly. Her work reflects her own family, who experienced separation during and after migration from Mexico to the United States. Born in Mexico and raised in a family with mixed immigration status in California’s agricultural Napa Valley, Correa Valencia lived in fear of deportation and had given up on going to art school until she received legal residency under DACA, the Obama-era policy that allows people who had been brought to the US as children to receive deferred action from deportation. She went to the California College of the Arts on a scholarship, previously unthinkable due to restrictions on student aid for undocumented people. In the years since, Correa Valencia has incorporated new mediums and collaborators into her work. Now a green card holder, she is able to travel to Mexico and work with artisans and fabricators there to bring her work to life. Jennifer Vogel wrote about Un Momento Mas / One More Moment, her 2023 aluminum and LED light sculpture that was fabricated in Mexico City, in “Light Unites Us” in the Winter 2024 issue of American Craft.

How do you describe your work or practice in 50 words or less?

My work explores the nuances of migration, visibility, invisibility, borders, and family separation through various mediums including textiles, social practice, and painting. After living in the United States for more than 25 years as a registered illegal alien, I use my family’s story to subvert the language and ideas that are assigned to immigrants.

You started out as a painter. How did you come to use craft mediums such as textiles and metal in your work?

During the pandemic, I was living with my in-laws, who are immigrants from El Salvador. While we were under lockdown, I began to grow frustrated with my lack of access to my painting studio. My mother-in-law, who grew up embroidering through the Salvadoran Civil War, taught me how to add textiles to my visual language.

You incorporate reflective safety clothing and glow-in-the-dark thread in your work. What do these materials mean to you?

My attachment to high-visibility and reflective materials comes from seeing how these materials play a key role in the labor industry in Napa Valley. While growing up here, I was always hyperaware of how these materials have defined the value of our existence relative to our labor and contributions to the wine industry. These materials are crucial in understanding how bodies can be both visible and invisible.

You’ve said you work with fabricators and artisans in Mexico to make your pieces come to life. Tell us about these collaborations.

Working with Indigenous artisans in Mexico has become a very special and important component of my practice. More often than not, Native artisans in my country are haggled for their beautiful, time-consuming work, and their crafts are devalued. I feel that I am in a very privileged position and choose to be intentional with my collaborations that highlight and support Native families whose traditions of craft date back to precolonial times. Supporting other Natives is an honor, and I believe that together we make the most beautiful work.

25 Estrellas: Sueños Para Mi Hija / 25 Stars: Dreams For My Daughter, 2022, repurposed American Flag on canvas, 60 x 50 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Capturados: Pájaros En Vuelo 1997 / Captured: Birds In Flight 1997, 2022, repurposed family clothing on canvas, 54 x 60 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Cuarto de Reunion #1: No Te Preocupes Hermanito, Ahorita Nos Toca a Nosotros. Volveremos a Ver a Mama y Papa. / Reunification Room #1: Don’t Worry Little Brother. It’ll Be Our Turn Soon. We Will See Mom and Dad Again., 2022, repurposed textile on black canvas, 72 x 57 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

If you could have work from any contemporary craft artist for your home or studio, whose would it be and why?

We currently have a very small tapete (rug) from Jacobo Mendoza, a Zapotec weaver from Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca, but it is a dream of mine to have a work by his mother and father. The Mendoza family members are some of my collaborators and arguably the most talented weavers in Oaxaca. We would also love to have work from Erin Riley, Jeffrey Gibson, and Marie Watt.

Which craft artists, exhibitions, or projects do you think the world should know about, and why?

I have always been incredibly impressed by Erin Riley. She is a weaver and makes the most impressive large-scale tapestries that depict the intimacies and trauma of being a woman. Her works are vulnerable captions of our everyday life that grapple with deep violence. Riley’s work is raw and I think she allows us all to reveal our truths, something that everyone should be doing!

Want to learn more about all of the craft artists you love?

Become an ACC member to receive a complimentary subscription to American Craft magazine and gain complimentary access to our shows, travel deals, and more!