Remembering: Paulus Berensohn

Paulus Berensohn, a potter of peerless warmth and spirit and an Honorary Fellow of the American Craft Council since 1998, died on June 15 at the Solace Hospice in Asheville, North Carolina. He was 84 years old.

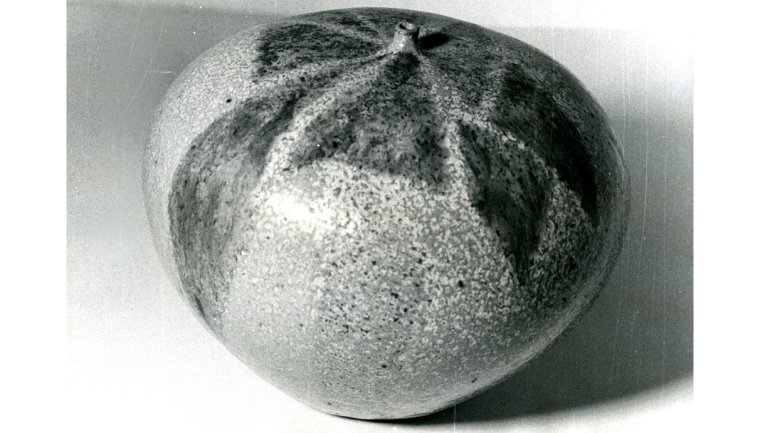

Berensohn’s work is simultaneously brilliant and serene, coming from a virtuoso uninterested in technique for its own sake. His pieces bring to oversized seeds or undersized mountains – natural forms, shot through with the recognizable and mysterious patterns of the earth. He was the subject of the 2013 documentary To Spring From the Hand: the Life and Work of Paulus Berensohn, and his 1972 book Finding One’s Way with Clay is a necessity to anyone interested in learning the pinched pottery method, its title hinting at his artistic outlook. For Berensohn, art had little to do with a product; it was process, discovery, life.

Growing up in New York City, Berensohn focused on dance. In his young adulthood, he alighted briefly on some of America’s preeminent institutions – Yale University, Columbia University, the Julliard School – but found their curricula too constrained. The transitions of his early life tell the story of a searching, curious artist. He left New York and returned numerous times; he studied dance and literature at Bennington College and, later on, danced in the company of visionary choreographer Merce Cunningham.

The pivotal moment of Berensohn’s artistic life came when he visited the Gate Hill Cooperative in Stony Point, New York. There, he saw the ceramist Karen Karnes at work. Watching the grace with which Karnes molded the clay and applied slip – the combination of expertise and instinct, mind and body – he underwent a kind of epiphany. “I thought, that’s a dance to learn,” he would later say in an oral history with the Smithsonian. Berensohn met M.C. Richards later that day, and soon after he would take a workshop she taught at the Haystack Mountain School in Maine. “Little did I know how important that jewel of a school would become for me,” he said.

A quick study, Berensohn himself soon began teaching, and he eventually found a longtime home in Penland, North Carolina, where he taught and lived for four decades. Though he was remarkably skilled, his classes focused as much on the creative process as on any particular method. He believed in nurturing an artistic ethos first and foremost. “Anything worth doing is worth doing even poorly, if you’re sincere, if it arises from your authenticity,” he said. “That for me has been the most important thing.”