Voices of Contemporary Shoemakers

From American Craft Inquiry: Volume 1, Issue 2

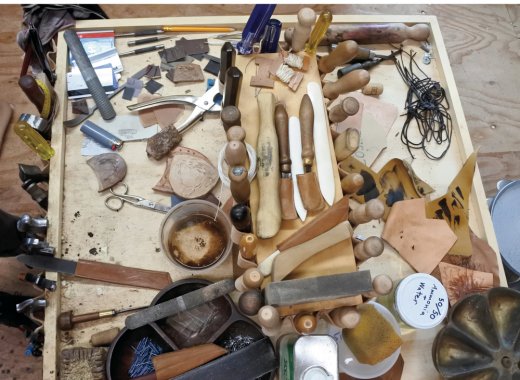

Walking into a shoemaker’s workshop, the first thing you notice is the smell—the heavy scents of leather, polish, and dust. Looking around, you see tools—the hammers and awls and pincers and finishing irons and razor-sharp knives. Most likely there is a wall on which countless spools of colorful thread hang, and close by is a sewing machine or three. On a table beside a low workbench are jars and bowls filled with tiny shoemaker’s tacks; beside these rest balls of hard yellow wax made using a secret recipe. You see the forms on which shoes are made, called lasts, everywhere—new lasts smooth with pristine curves, as well as lasts that have been altered with leather and cork to reflect the shape of a particular client’s foot. Lasts hang from the ceiling or are stacked on shelves; they wait on benches and idle on the sanding machine.

Chances are the shop is messy. Chances are there are more tools than you can imagine using, many of which you have never seen. And then, after the first overwhelming glances, your eyes rest on the shoes, maybe samples, or trials, or failures. Maybe client shoes in progress. And here your eyes widen in disbelief. These shoes are made by hand? These beautiful shoes are made in this dusty, disorderly shop? This is the part that cannot be described. It is the magic. It must be elves, because to make such a beautiful object, one so uniquely suited to the body and temperament for which it has been made, surely is the work of a secretive, thoughtful, and wholly magical creature.

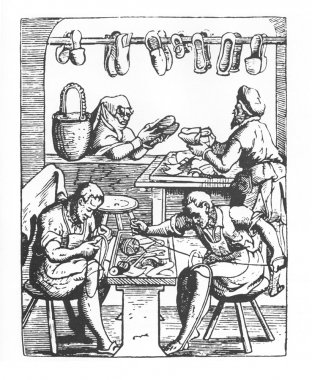

Elves first appeared in the workshops of German shoemakers in 1806, written into a Brothers Grimm fairy tale that has since become legend. Since that time, a static image of the humble shoemaker has embedded itself in our cultural imagination as an apron-clad old man perched on a stool in his workshop. Today, however, a new story is emerging in which shoe and boot makers are redefining the craft by constructing contemporary footwear using traditional techniques and tools. But even with the craft alive and responding to the contemporary world, so few shoe and boot makers remain, and many believe that shoemakers, like elves, are the stuff of legend.

In the United States, it is hard to know how many shoe and boot makers are working today, or even how many independent shops exist. There is no directory, and like many artists and craftsmen, most professional shoe and boot makers spend more time crafting shoes than promoting shoemaking as a living craft. Certainly, there are more cowboy boot makers than shoemakers, but the population of boot makers is nowhere near what it was 50 years ago, when nearly every small town in Texas boasted a boot shop. Shoemakers also live and work along the coasts, but there, too, the numbers are dwindling. The increasing sparsity of professional shoe and boot makers is striking, and why this is happening is a complex question.

Most people who are interested and involved in shoemaking go through regular cycles of bafflement at the state of the trade, questioning why they do it, and whether or not it is a viable profession. To make a shoe is a surprisingly complex undertaking, with each pair being a multi-layered, three-dimensional puzzle that must be completed twice, but in mirrored form. Variance of just a few millimeters upsets the symmetry, not to mention the fit and feel of the object. I have been a shoemaker for about five years, and over the course of this time, I have met professional makers and hobbyists around the world – a peculiar and wonderful group of individuals. The fact that people outside this community tend to know so little about the trade has been striking to me, as has the dire lack of published technical information.

As I meet shoe and boot makers and visit their workshops, I find myself asking the same questions – inquiring about technical advice, trying to learn the history of the trade, to hear their views on where the trade is going in the future, or just to see how different workspaces are arranged and why. This article is a result of some of those visits and conversations. Each of these makers has been in the trade between five and ten years. They come from around the country. When I began, I expected diverse responses, so I was surprised by the similarity. While individual voices and experiences are unique, together we form a remarkably unified portrait of what it means to be a professional shoe or boot maker in the United States today.

Past and present

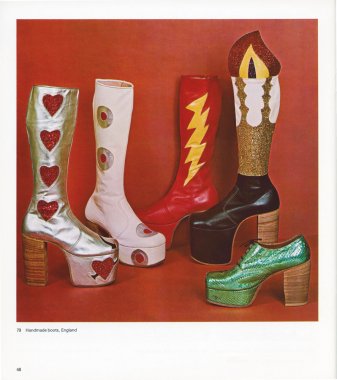

The heyday of shoe and boot making arrived during the post-World War II boom. Chris Francis, a shoemaker and artist in Los Angeles, explains that “after World War II, many, many shoemakers came over from Europe because the cities had been decimated. In the ’50s, there were 400 recognized shoemakers in the United States – 400 whose names we know; that’s not even counting the many people who were making, but who didn’t sign their work or whose work didn’t survive.”1 As a shoemaker in Hollywood, Francis channels this period, specializing in vintage-style reproduction and repair, as well as in contemporary design. “The quality of work [from that era] is mind-blowing. I have clients who want a specific shoe reproduced, but I can’t get the leather or that really fine thread. Then there is the simple fact most of those guys had 50 years of experience that I don’t have.” During that time, handmade shoes were not uncommon, making for unique designs and constant technical innovation as makers competed with each other, striving to create the best work possible for their clients. There were also many small designers and makers spread across the country, making for greater regional distinctions in both design and craft.

Shoe and boot makers today are no less competitive or less keen to create the best possible footwear, but they are up against incredibly tough odds. Previous generations of makers worked their way through formal apprenticeships, which provided training in the craft and the business skills to support the craft. Today, the apprenticeship system has largely disappeared, forcing those working professionally to figure it out as they go. Moreover, they must do this while working in a culture that largely does not understand the complexities of the shoemaking process, or the real meaning (or cost) of materials and time. One maker, using a version of an Oscar Wilde quote, which stated simply that Americans know the cost of everything and the value of nothing. Unlike previous generations working within an established system, makers today are unclear, and often in disagreement, about how the trade can or should move forward.

Some makers feel that because the established mold for learning the craft and then running a shop has been broken, there is incredible freedom to tread new paths. As Salvador Castillo, a shoemaker at Willie’s Shoe Service in Los Angeles says, “being a craftsman means finding beauty every day, and as a trained professional, I feel free to explore and see where that takes me.”2 This freedom creates a space for great innovation and variety in both design and technique. However, as invigorating as this freedom can be, many experience deep insecurity about whether there will be enough sustained interest in the process and product to support professional makers into the future. To sink the time, energy, and resources into a craft with an uncertain future may well be a foolhardy adventure, and requires innovation within one’s practice. It is, however, this very uncertainty that propels makers to grow efficiently, as they must figure out how to fix machines, find materials, work with clients, and most importantly, master the techniques of shoe and boot building.

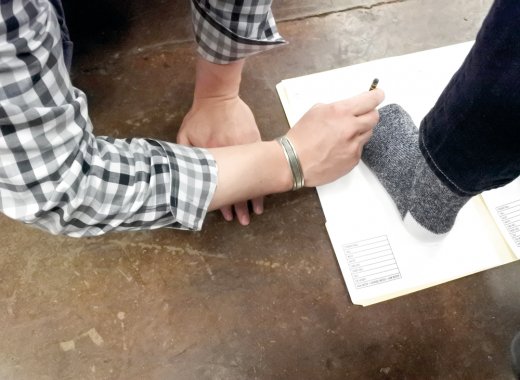

As makers grow as craftsmen, they constantly evaluate and reevaluate their skill and the market around them, creating a practice that is unique to their hands, their aesthetic, and their surroundings. As such, the trade is being redefined by today’s working professionals. Nevertheless, the day-to-day workings of running a shop remain true to the past – a feature of contemporary shoemaking that remains remarkably similar across the country. This continuity owes largely to the nature of the work itself. Shops are run by solitary makers because taking on employees requires scaling up, which most small shops can’t support financially. Makers work with individual clients following long-established systems of measuring, designing, and making. Fanciful and functional footwear unique to both maker and client emerges from a collaborative process of artistry and craftsmanship.

The tools in the shoemaker’s workshop also remain the same; most of the hand tools, and even the sewing machines, are the same kinds as those used by previous generations. The relationship between shoe and boot makers and their tools has always been close, because shoes are largely built with hand tools. After years of use, these tools bear the physical marks of their user. Chris Francis describes his relationship with vintage tools:

I spend like 50 to 100 hours on a pair of shoes, and of course big pieces of me go into them. But all that energy is being transferred from me to the shoes through my tools. Think about tools that were in a workshop for years absorbing and transferring that energy. It’s a really powerful thing.

Beyond just tools, and even in the midst of a newfound freedom, many techniques continue to be passed down from master to learner. With continued support, those learners will become masters in their own right. Most of those working today, however, are quick to say that they are not masters, even as their work appears masterful to those outside the trade. Jesse Moore, a shoemaker in New York states, “[I have] been making shoes around 10 years, and am still so far from where I want to be. I think that’s part of what keeps me interested. It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done.”3

To those who have not made a shoe, it is difficult to fully explain how many steps, and how much time and skill and knowledge, go into the making of a single shoe. There is incredible nuance to the curve of a topline and the feathering of a skive. Shoemakers are designers, artists, and craftsmen who are also running a business rooted in the poetry of a functional object. It takes years of slow progress for a shoemaker to develop, though the world moves much faster than 50 years ago. Still, modern shoemakers hold on to the tools and techniques of their teachers for good reason: They enable makers to craft the most beautiful and longest-lasting footwear. So while the world outside is changing, the work being produced in shoemakers’ workshops is as exciting and fresh as it ever was, even as makers embrace creativity and contemporary life.

Vision and value

Speaking with shoe and boot makers around the country, it quickly becomes clear that style differs greatly with geographical location and the ability, experience, training, and the particular vision of each maker. There are, however, many similarities in shoemakers’ methods and habits, most notably a willingness to share information and process details, in hopes of keeping the trade alive. This openness is very different from previous generations of makers, who were notoriously secretive. Reid Elrod, a shoemaker in Portland, Oregon, describes the generational shift:

It used to be an old boys’ club. The makers were amazing, but there just wasn’t room for people who didn’t fit in with that idea of who a shoemaker was. … But we are here now, and we have all the passion that they did – maybe even more because we’ve had to struggle so much to get to where we are – and we get to make a new club where we kind of watch out for each other and take people in who are really interested.4

Even with a newfound willingness to share information and provide room for those who want to learn the craft, shoe and boot makers have not been able to shake a fierce independence that does not always lend itself to working together. This independence – which I think emerges in part from an emphasis on individual style and original artistic vision – is part of what makes shoe and boot makers compelling as individuals, but ultimately it holds back the trade. Even with a willingness to share, there are few opportunities created or taken to do so.

The notorious independence of these makers is what caused the near-death of the trade 30 years ago. No one was willing to teach or share what they knew, and with no apprenticeships system, there were no new makers. Even today, the numbers of shoemaking professionals continue to dwindle. Pascal of Hollywood Riff Raff describes the craft of shoe and boot making as “a ship that is being fired on and is going down. All the makers are on the ship and they all have buckets to bail water, and if they worked together they might be able to save the ship. The problem is that instead of bailing, they are standing around arguing about whose bucket is better.”5

Asked why he has so firmly tied himself to a sinking ship, he answers, “I’m French. I would rather go down with dignity than win with cheap tricks.”

It can be argued whether the ship is going down, but it is clear that the trade is experiencing dramatic changes, and its destiny is unknown. Many believe that this generation of makers will be among the last. It is also true that we are experiencing a resurgence of interest and support.

Nonetheless, it can be hard for outsiders to understand. Makers today are working against the accepted modalities of our time — working slowly and deliberately in a culture that values fast fashion, rapid change, and low-cost, disposable items. Anne Marika Verploegh Chassé characterizes these cultural norms as a lack of curiosity and respect for process, and she finds them at odds with her work as a shoemaker in New York:

People want their shoes to last forever, but they don’t want to wait for as long as it takes me to make it. They want these beautiful objects made right here by these hands, but then there is the reality of what a living wage is in the United States. The thing is, everyone dreams of a handmade shoe, and sometimes the dream wins. Maybe it’s just the dreamers who get handmade shoes made.6

Even those interested in handmade footwear often do not have a full understanding of the process that goes into shoemaking. It is a kind of illusion. When done well, the process is invisible.

Raul Ojeda, owner of Willie’s Shoe Service, describes this tension between desire for high quality and artificially low prices.

People want to have very special things made just for them, but they don’t realize how much work it takes. And even when they do, even if they get hooked, there is real confusion around retail today. People have a mindset that they need the cheapest thing, even if falls apart right away. Then they know that retail has a 50 percent markup, so they wait for the sales. My shoes aren’t going on sale, and there is no markup. People are paying for the best materials and my time and skill, which isn’t cheap. A huge part of my business is spent educating people about this. It’s crazy – maybe even stupid. But I’m still here. And I’m going to be here until it’s no longer possible.7

The disparity between a desire for high quality and low-cost goods does not fit with shoemaking, a craft that is incredibly labor intensive and produces goods that can be used and repaired for years. But this is an aspect that makes it so valuable within our culture today: it models a way of being in the world, as both a consumer and a producer, that is at odds with the messages of consumerism received in the media.

When asked what they wished people knew about the trade, each shoe and boot maker I interviewed expressed a desire for more people to understand and appreciate what goes into the making of each pair of shoes. “People don’t have a clue,” says Reid Elrod. “They know it takes a long time, they know it’s expensive, but they really can’t understand how much goes into it. I mean, just try to keep your knife sharp. There is so much skill at every step, and at the end, all they see is a pair of shoes.”8 The depth of dedication, energy, and ambitious affection that goes into the work is something that is hard to see from the outside. Like any love, one must be in it to fully feel its depth. At the end, all there is is a pair of shoes. This is the poetry of the craft.

Making and learning

As I mentioned earlier, figuring out how to learn is one of the most challenging parts of becoming a shoemaker. One generation ago, the few shoe and boot makers there were largely did not take students, forcing would-be students to travel to learn. The regionalism I observed in the craft was actually, paradoxically, a product of significant travel. “When I started, it was like a wasteland,” says Jesse Moore, a New York shoemaker who learned largely in the UK and Sweden. “There were a very small number of [cowboy] boot makers who taught classes, but other than that, it was just like tumbleweeds blowing in the wind. Nothing.” To alleviate the problem, Moore started bringing in British shoemakers to teach courses in New York. Jeff Mandel of Exit Shoes began learning at a shoe school in Washington state, and continued from there. He spent additional time at a school in the Netherlands and worked independently with several makers there. “I was incredibly lucky to have gone to school for this. But even with that, I’m learning an incredible amount on every pair,” he says. “Each new set of feet is its own set of problems that I identify and figure out. That’s really what makes it interesting.”9

Without formal training, most makers spend time learning, and then a lot more time solving problems in their shops. Francis Waplinger learned in Florence, for example, and is one of the few shoemakers lucky enough to have undertaken a formal apprenticeship. “It was crazy,” he says, laughing. “The master says do something and you do it. Sweep, and I swept. I spent a lot of time trying to find lasts.”10 He knows how lucky he was, as these opportunities are few and far between.

Beyond spending time in someone else’s workshop, makers turn to online videos and trade books. Josh Duvall, a cowboy boot maker in Oklahoma City, learned by reading books and watching videos. But books and videos weren’t always able to help, so Duvall also took problems he ran across to local boot makers for advice. Learning through books and videos left him with questions that he’ll be trying to answer for a long time.

I’m at a point where I feel comfortable making a boot. I’ve learned the questions to ask clients about how they want their boots to fit, so that part’s getting a lot better. But even though I feel comfortable going through the steps and my clients are happy at the end, I don’t feel like I fully understand why things work the way they do. Like, if I alter one thing, what effect will it have on down the road of the building the boot, or, even more importantly, on the wearing of the boot?11

Emery Downan, a cowboy boot maker in Coalgate, Oklahoma, studies his grandfather’s old shop-made boots for clues to how they were built and why. Downan may have grown up around handmade boots, but he’s the first bootmaker in his family. He bought his boot shop complete after the Texas maker died; included were patterns and half-completed boots. “I pick up those boots every day – sometimes twice a day – and I can still find new things on them to learn from,” he says. He continues:

I mostly make boots for working people. Not because of that, but related to it, I want to make the best boot that I can with the techniques and materials available to me. I feel that by asking me to make their boots, people are putting a fair amount of trust in me, and I can’t help but take that seriously. Part of it is pride, but it’s also just the desire to create the best thing possible that you know will help these people in their daily lives. That may be in terms of performance, but it may be just feeling more confident in how they look and move.12

No matter their training, shoe and boot makers feel a responsibility for their clients’ well-being. Each pair of feet is approached new, and each set of footwear builds on prior knowledge. Pascal says that his clients are not just buying one pair of boots; they are buying every pair that he has made.

Imagination and reality

With so few shoe and boot makers, and such slim understanding of the trade by those outside it, it is no wonder that the future of the craft is in question. It is a slow process in a world of instant gratification. Bespoke shoes are expensive products in a world of artificially low prices. The work is physically demanding and tedious. Mastering any one of the many parts of the process takes years, and the learning curve can be costly and demoralizing. And yet, there are still a smattering of shoemakers across the United States who are working, practicing, building, experimenting, questioning, and developing. And there is still a demand for handmade shoes and boots. After all, footwear satisfies something in each of us. It hovers between imagination and reality. Shoes are objects of fetish and desire. They are utilitarian. They are abused and coveted equally. They protect our bodies from the harshest conditions. They propel us forward as we move through space and time. They wear thin. They wear out. They are dreamt of. They are discarded without thought. We all have stories about our footwear. And given the variety available and the extreme differences in how they cause our bodies to both feel and move, it is hard not to see shoes as signifiers of who we are as individuals and as groups, of our personal relationship to the world, and of what we are willing to tolerate.

Shoe and boot makers work between dreams and reality. The making itself is intensely physical, but these craftsmen are fully aware that the shoes and boots they make occupy a unique position in their clients’ dreamscapes. These makers know that their work is far more than just to shoe their clients’ feet. Contemporary shoemakers satisfy something in us – something that cannot quite be named – by giving us something to walk on and in and through, something that elevates us to become the individuals we imagine ourselves to be. Shoes and boots help us to embody the people we want to become through a masterful a sleight of hand, the creation of a feeling.

Read more from the second issue purchase issue

1. Francis, Chris. Interview with Amara Hark-Weber. Los Angeles, CA, May 15, 2017.

2. Castillo, Salvador. Interview with Amara Hark-Weber. Los Angeles, CA, May 16, 2017.

3. Moore, Jesse. Interview with Amara Hark-Weber. Brooklyn, NY, April 20, 2017.

4. Elrod, Reid. Telephone interview with Amara Hark-Weber. May 9, 2017.

5. Hollywood Riff Raff. Interview with Amara Hark-Weber. Los Angeles, CA, May 13, 2017.

6. Anne Marika Verploegh Chassé. Interview with Amara Hark-Weber. Brooklyn, NY, April 19, 2017.

7. Ojeda, Raul. Interview with Amara Hark-Weber. Los Angeles, CA, May 15, 2017.

8. Elrod, Reid. Telephone interview with Amara Hark-Weber. May 9, 2017.

9. Mandel, Jeff. Telephone interview with Amara Hark-Weber. May 2, 2017.

10. Waplinger, Francis. Interview with Amara Hark-Weber. Southampton, New York, April 21, 2017.

11. Duvall, Josh. Interview with Amara Hark-Weber. Oklahoma City, March 21, 2017.

12. Downan, Emery. Interview with Amara Hark-Weber. Coalgate, OK, March 22, 2017.